While the US and the EU look at different ways to add tariffs to China-made electric vehicles to prevent supply disruption, the reality is that overall demand for EVs appears as though it is starting to peak.

Such was the topic of a new FT report that looked into why Americans aren't buying more electric vehicles.

“It’s just not accessible to us at this point in our life,” one couple told FT, who said they were looking for a more affordable vehicle. They went with a $19,000 Honda Accord after a trade-in, since only five new EV models under $40,000 have hit the market in 2024, the report says.

FT reported that high car prices and rising interest rates, which increase monthly lease payments, combined with concerns about driving range and charging infrastructure, have dampened buyers' rush to buy EVs, even among environmentally conscious consumers.

Everett Eissenstat, a former senior US Trade Representative told FT: “There is no question that this slows down EV adoption in the US. We are just not producing the EVs the consumers want at a price point they want.”

Lack of charging infrastructure and range anxiety also remain concerns. Overnight home charging is ideal for EV owners, but those in apartments, especially in states like California, rely on public chargers. The U.S. has 64,000 public charging stations, compared to 120,000 petrol stations, with only 10,000 being fast chargers. As we noted weeks ago, the Biden's administration's plans to build charging infrastructure have been an abject failure.

EV buyers are also concerned about limited range, long-distance travel, cold weather, and towing reducing battery life.

“What we’re seeing is the pace of EV growth is faster than the rate of publicly available charger growth,” said John Bozzella, chief executive of US auto trade group the Alliance for Automotive Innovation.

The Biden Administration, meanwhile, has been tackling Chinese supply with tariffs. Last month, the administration imposed new tariffs on Chinese imports, including a quadrupling of tariffs on electric vehicles, a tripling on lithium-ion batteries to 25%, and a new 25% tariff on graphite used in batteries, the report noted.

“This sends a clear signal to China: don’t even think about exporting your cars to the United States,” Wendy Cutler, a former trade official and vice-president of the Asia Society Policy Institute said.

Jennifer Harris, a former economic adviser to Biden added: “The idea that we should just open our gates and have a bunch of systematic Chinese economic abuses ...and that that’s the answer to climate change is incredibly naive and short-sighted.”

But these tariffs could prevent prices from falling, according to Ilaria Mazzocco, chair in Chinese business and economics at CSIS.

“It’s not just that the same car costs less in China, it’s that in China you have a wider variety. US automakers will have the leisure of not having competition, and they’ll be able to focus on making these high-cost trucks,” Mazzocco said.

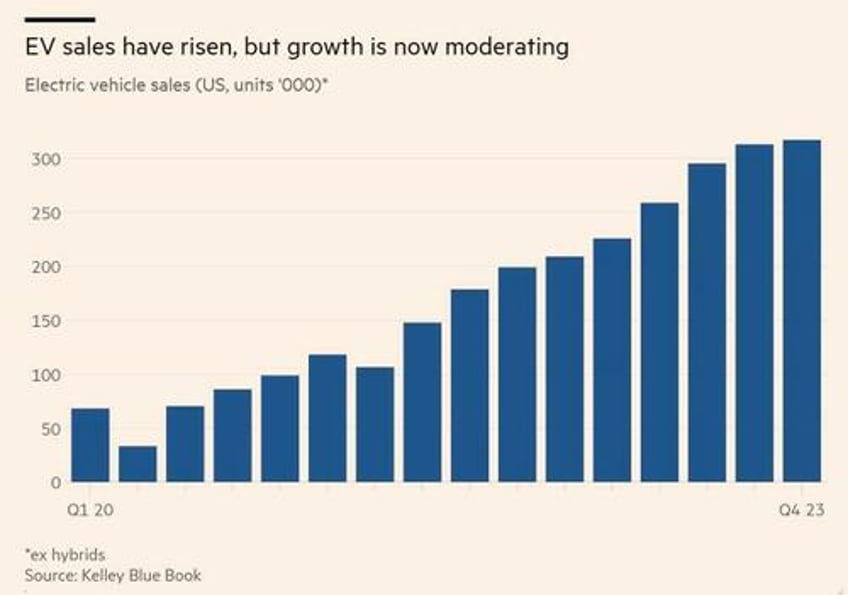

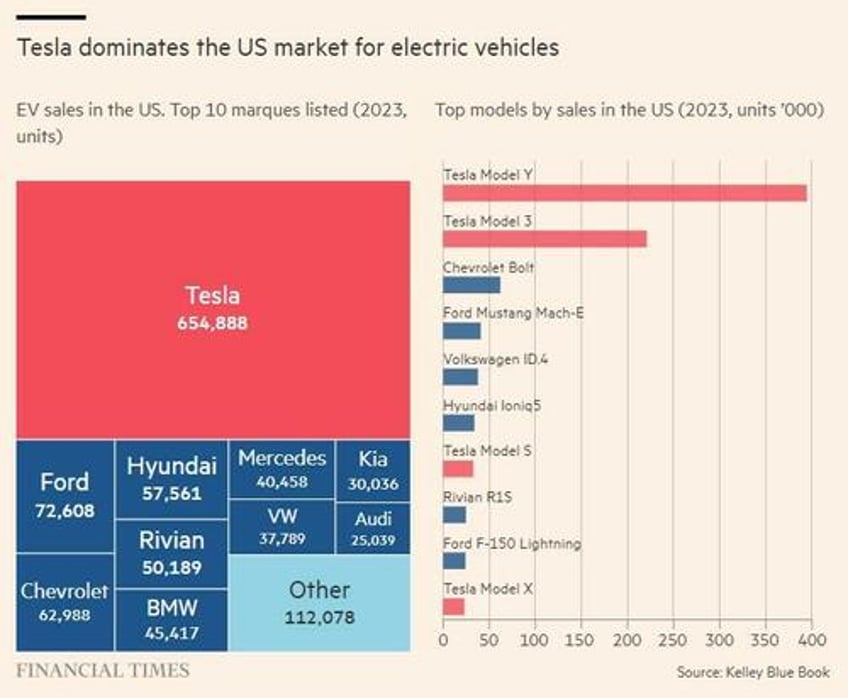

And so, the FT report notes that while EV technology and popularity are growing, sales growth has slowed. As a result, automakers are reconsidering manufacturing plans, shifting focus from EVs to combustion and hybrid cars for the US market.

EVs are caught between President Biden's goals of tackling climate change and protecting American jobs. Biden aims to cut US greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels by 2030, with widespread EV adoption being crucial. However, he wants to avoid imports from China, the largest EV producer and key raw material supplier.

Analysts warn that this protectionism could increase EV prices in the US, potentially stalling sales and leaving the US behind China and Europe in EV adoption.

Meanwhile, the World Resources Institute states that 75-95% of new passenger vehicles need to be electric by 2030 to meet Paris agreement goals.