By Garfield Reynolds, Bloomberg Markets Live reporter and strategist

Bonds are cruising toward a likely bruising by pricing in an almost immediate Federal Reserve pivot to rapid, deep interest-rate cuts. The risk is that they will prompt the central bank to push back hard enough to set off fresh cross-asset turmoil.

Markets see about an 80% chance the Fed will trim its benchmark in March. While inflation has slowed substantially and jobs growth has cooled, it’s hard to see the justification for such one-sided bets. Indeed, the latest consumer-price and payroll numbers surprised modestly to the upside, suggesting the Fed is still likely to be far from convinced its policy of returning inflation to target has been a success.

The confidence in a March cut is also puzzling given the short runway. There are just two more sets of reports before that month’s meeting, considering payrolls and the two most relevant inflation readings: the Bureau of Labor Statistics figures, and the PCE deflator the Fed targets.

The Fed may well seek to address this dislocation by means of an “intervention” much as it did back in early 2017. That was when then Chair Janet Yellen led a concerted campaign from officials to say future meetings were “live.” Traders responded by rapidly boosting odds of a rate hike to 90% from less than 30%.

Fed Chicago President Austan Goolsbee took a step in that direction at the end of last week by saying the market had gotten ahead of itself. There’s also potential for further pushback from speeches this week. Policymakers have consistently insisted that rate cuts are a long way off, even after acknowledging in December that they are unlikely to deliver any more hikes.

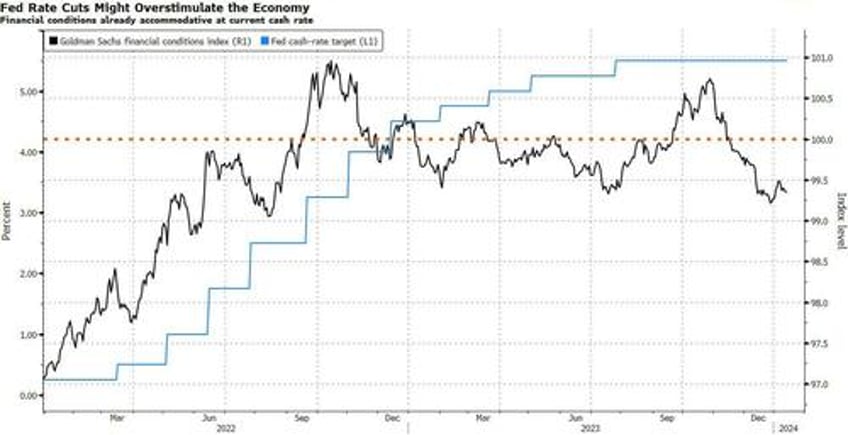

If a cut in March currently seems a stretch, the 6 1/2 reductions priced in by year-end appear even more outlandish. That sort of trajectory would require a full-blown recession, which flies in the face of recent data pointing to resilience in the economy. Financial conditions are also as loose as they’ve been in more than a year, highlighting the risk that early rate cuts would revive inflation.

The disconnect between the market and the Fed may owe much to the heady impact on investors of bonds that once more have decent yields. With traders certain they have the direction of Fed policy right, higher coupon payments relative to recent history seem to offer a large enough buffer to ride out any fresh bursts of central-bank hawkishness.

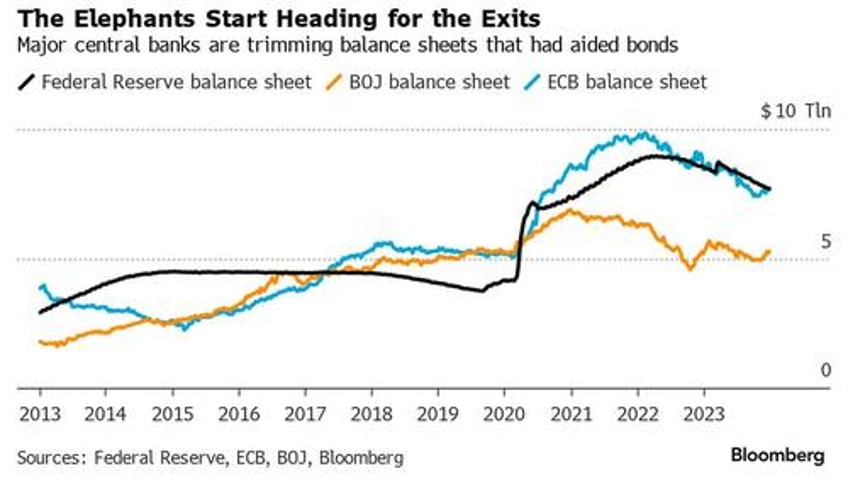

That enthusiasm could easily evaporate, especially if there are fresh fears about rising US bond supply. Most governments are forecast to boost bond issuance this year, even as the majority of central banks will either be running down their balance sheets or moving toward that process.

At the same time, markets remain vulnerable to Fed surprises, especially as many companies need to refinance borrowings that were taken out in the era of record-low interest rates. The weight of expectations for a rapid shift to lower rates means equities are exposed to any uptick in discount rates, with forward P/E ratios sitting well above pre-pandemic norms.

Bonds may show more resilience to a stubbornly hawkish Fed than equities are likely to do given the way investor demand has increased whenever whenever yields have risen. But both asset classes remain vulnerable until the divergence between market pricing and the Fed is resolved.