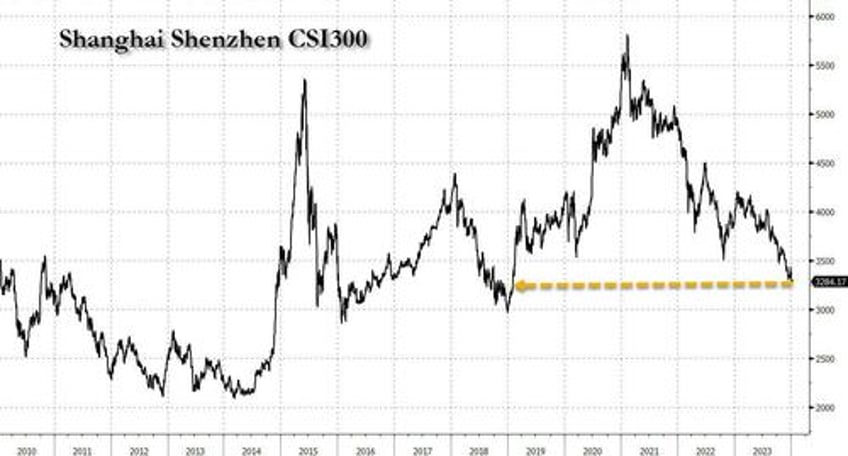

While most western markets are at or near all time highs (that includes most European bourses as well despite that continent's quiet slide into recession), what was once the darling of the smart money crowd, China, has been quietly swept under the rug for all all polite capital markets purposes and conversation, and for good reason: China's stock market is not only down almost 50% from its Feb 2021 high, but also at the lowest level in 5 years and practically unchanged for the past decade!

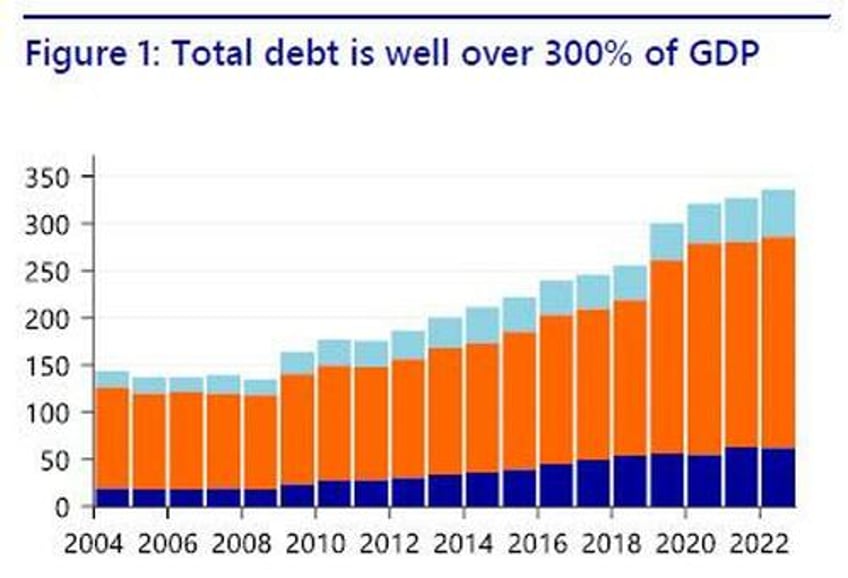

Alas, with China's debt at record highs, over 300% of GDP...

... all those hoping for a quick resolution to the biggest problem plaguing China's economy and markets, namely the lack of a "bazooka" in new debt/loan creation which can backstop the imploding property sector, kickstart the mobirbund economy and spark a market rally, there is little hope that anything can change.

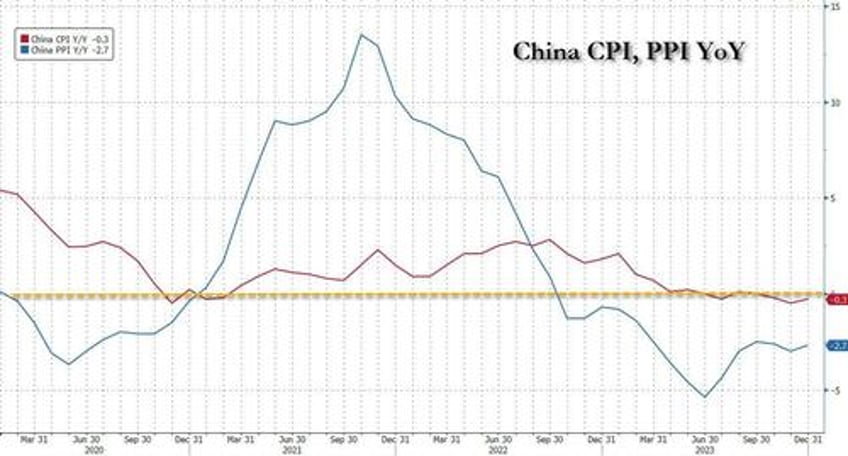

Which is a problem because in the meantime, China's key economic indicators continue to deteriorate as the (now 2nd most populous after India) country slowly slides into the toxic spiral of Japanifying deflation.

Let's take a look at what was reported overnight, starting with the latest CPI and PPI data out of China: in December, the country's CPI dipped again, sliding 0.3% from a year ago (beating the estimate of a -0.4% drop) mainly on a low base of food prices; the number has now failed to grow on 4 consecutive months as deflation becomes increasingly embedded in China's economy. On a sequential basis, CPI did manage to stage a modest, 0.1% MoM increase compared to November (when it slumped -0.5% MoM).

- Food: -3.7% yoy in December vs. -4.2% yoy in November.

- Non-food: +0.5% yoy in December vs. +0.4% yoy in November.

At the same time, PPI, or factory gate inflation deflation, shrank -2.7% y/y; worse than the -2.6% est, but better than the -3.0% slump in November. This is now the 14th consecutive month of PPI deflation in China, a longer stretch than even the immediate aftermath of the covid lockdowns.

Some more details from Goldman:

- In year-over-year terms, food inflation rose to -3.7% yoy in December from -4.2% yoy in November primarily on easing pork prices deflation. On major food items, inflation in pork prices rose to -26.1% yoy in December from -31.8% yoy in November, while inflation in fresh vegetables edged down to +0.5% yoy in December from +0.6% yoy in November.

- Non-food CPI inflation edged up to +0.5% yoy in December from +0.4% yoy in November, primarily due to improved non-food goods inflation. Fuel cost deflation moderated to -1.4% yoy in December (vs. -2.9% yoy in November), partially offset by falling transportation equipment prices (-5.4% yoy in December vs. -5.0% yoy in November). Services inflation was flat at +1.0% yoy in December.

- Year-over-year PPI inflation rose to -2.7% yoy in December from -3.0% yoy in November, largely on a low base. In month-over-month terms, PPI inflation rose to 1.1% (annualized, seasonally adjusted) in December (vs. -4.5% in November). PPI inflation in producer goods edged up to -3.3% yoy in December from -3.4% yoy in November, and PPI inflation in consumer goods was flat at -1.2% yoy in December. NBS commented that PPI deflation continued on lower prices of crude oil and weaker demand of some industrial products.

The bottom line, both headline CPI and PPI deflation continued in December as soft demand of some industrial products and weak energy prices contributed to persistent PPI deflation. Meanwhile, CPI deflation reflects dampened domestic demand due to ongoing property downturn and stressed labor market.

As Goldman concludes, "the broad-based disinflation pressure points to a prolonged reflation path for China."

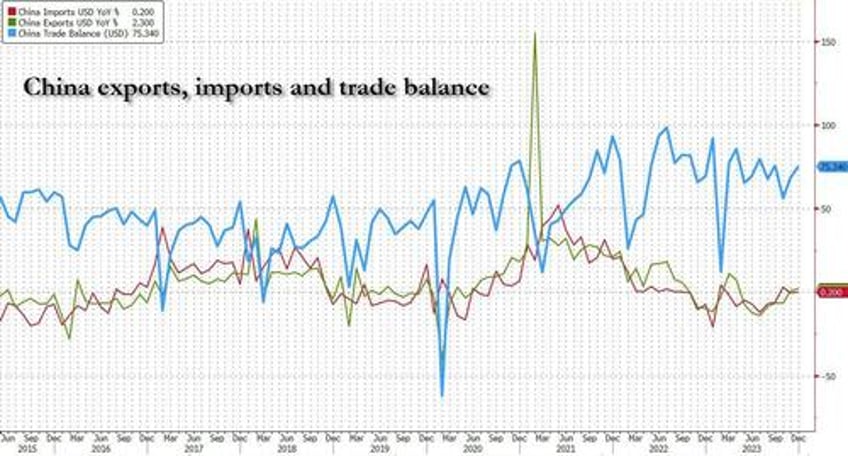

There was some good news overnight, when China also reported its latest trade data, which saw exports and imports both print every so slightly above expectations, if only barely. Specifically, China’s December exports rose 2.3% y/y (in USD terms) above the est. +1.5% and higher than the 0.5% November print which followed 6 months of export shrinkage. Imports also rose slightly, reversing the recent trend of declines, and beating estimates of -0.5%. Like exports, China's imports had declined for much of 2023.

Despite the very modest improvement in December, China recorded a drop in the value of both its exports and imports for the full 2023, in a further sign of slowing economic growth. Customs authorities say exports amounted to 3.38 trillion dollars. That's down 4.6% from a year earlier, and the first contraction in seven years. China's annual imports also contracted by 5.5 percent on the back of weak domestic demand. That was largely due to a prolonged slump in the real estate market and a tough employment situation.

And as the west does everything it can to appease Beijing and preserve access to the Chinese market, one may ask if the west is truly China's friend, to wit: shipments to the US dropped 13.1%, the result of tensions between Beijing and Washington over semiconductors and other technologies; at the same time exports to Europe declined 10.2 percent, and to Japan they fell 8.4 percent. There was a silver lining: shipments to Russia (primarily cars) soared 46.9%. That pushed up the value of all trade with Russia to a record 240.1 billion dollars.

But wait, there's more, because while China remains mired in deflation as its mercantilist economy fails to reboot, so did China's all important credit creation.

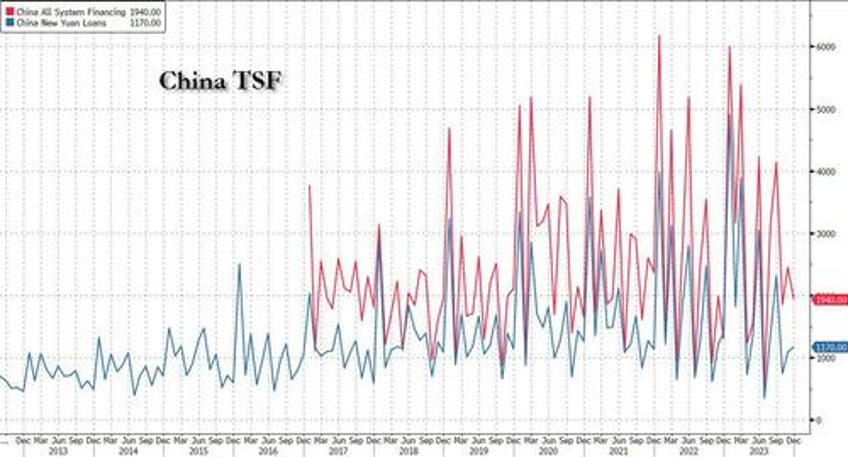

Completing the trifecta of Chinese data releases overnight, the PBOC reported December's new RMB loans, TSF and M2 data all of which came in below expectations, showing sluggish credit demand despite what Beijing claims is an "accommodative" policy stance. Here are the key numbers:

- New CNY loans (flow, reported): RMB 1.2 trillion in December, missing the Bloomberg consensus: RMB 1.4tn

- Outstanding CNY loan growth: 10.6% yoy in December; and below the November: 10.8% yoy

- Total social financing: RMB 1.9tn in December, missing consensus: RMB 2.2tn

- M2: 9.7% yoy in December missing Bloomberg consensus of 10.1% yoy.

While credit creation in December was dismal, the composition of loans data painted a slightly less disappointing picture than the headline loan number - both corporate and households' RMB loan growth improved slightly in December from November last year, but the residual component, which includes loans between financial institutions, likely contracted in the month and dragged on overall RMB loan growth. In addition, corporate medium to long term loan growth accelerated while bill financing slowed by contrast.

That said, the slowdown of TSF growth was broad-based across different debt instruments - besides lower new loan flows, bond net issuance and shadow banking credit also moderated. The PBOC recently warned against funds circulating within the financial system and kept repo rates for financial institutions relatively high in late last year. This likely contributed to the contraction of loans between financial institutions and shadow banking credit in December.

Still, perhaps in light of the dire data, we have seen incremental monetary policy easing signals - or at least jawboning - in recent days, including PBOC's statements that they would utilize various monetary policy tools such as "open market operations, medium-term lending facility, relending, rediscount, and RRR adjustments" to "ensure TSF grows rapidly throughout the year". Goldman writes that "taken into consideration these comments and the deposit rate cuts by commercial banks late last year, we continue to expect the PBOC to cut policy rates (7-day OMO rate and 1-year MLF rate) in this quarter, followed by two more RRR cuts and one more policy rate cut in the rest of the year."

Perhaps the clearest indicator of just how credit-starved China's economy is, is the chart of M2: as shown below, M2 growth declined to 9.7% yoy in December, and moderated to +4% month-over-month annualized, vs +9.8% in November. At the start of the year, M2 was growing 12.9%. For context, in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, M2 rose 30%. The ongoing collapse in M2 growth was the result of slower loan growth and the contraction of financial leverage.

At the end of the day, all of the above weakness is a byproduct of just one thing, too much debt, and absent some massive debt-for-equity restructuring or some wholesale credit overhaul, China will not only not be able to grow, but will remain on a downward slope as its economy enters the infinite gravitational pull of Japanification.

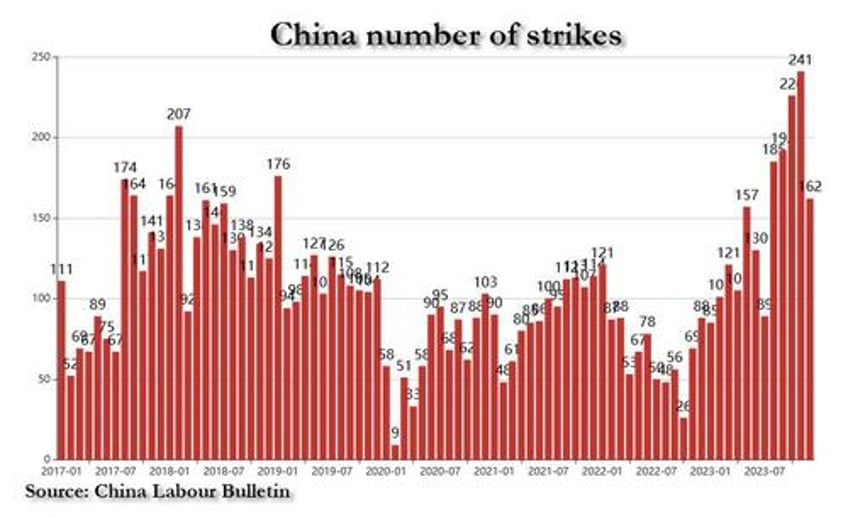

And while a quiet, painless sovereign suicide may be an option for Japan with its demographic disaster and rapidly aging population where more adult than baby diapers have been sold for years, for China - which still has a young, vibrant and increasingly angry population - this is not an option as the coming tidal wave of angry protests and strikes, could easily result in the one thing the Chinese Communist Party dreads the most, a revolution.

But that's precisely what China will get unless it figures out a way to bazooka its way to at least a few more years of growth. Why? Because as the following map of Labor protests and strikes across China makes all too clear, Beijing has almost run out of time.

Incidentally, the growing urgency of Beijing to do something to arrest the economic collapse may explain why we are seeing some aggressive bets on outsized returns in Chinese stocks, in the form of surging FXI and KWEB call trades.

two days ago it was FXI. Today it's FXI and KWEB https://t.co/Psijg12PbX pic.twitter.com/cbUzhr9eWx

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) January 12, 2024

Indeed, even Morgan Stanley is now warning that with China's GDP deflator stuck at around -1.4% for three quarters in a row, the longest deflation period since 1998, as the reactive policy easing has failed to counter the strong tightening effect of housing and LGFV deleveraging, constituting de facto fiscal austerity, "the need for more central government leveraging is becoming a consensus among policy advisors, investor questions have concentrated on the size, speed, and mix of stimulus required to reflate China's economy." The answer: a lot, and right now... unless Beijing is willing to risk everything.