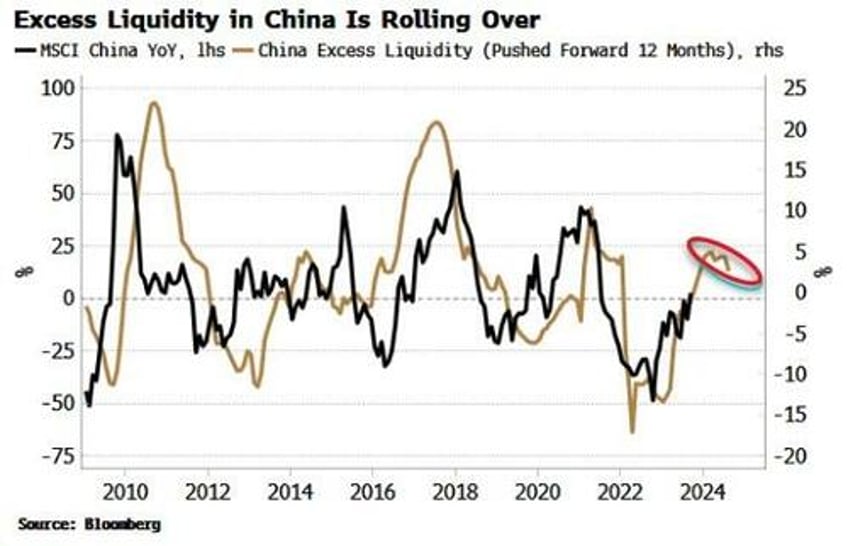

Liquidity in China is still struggling to get a foothold, posing an ongoing headwind to a recovery in the country’s stock market.

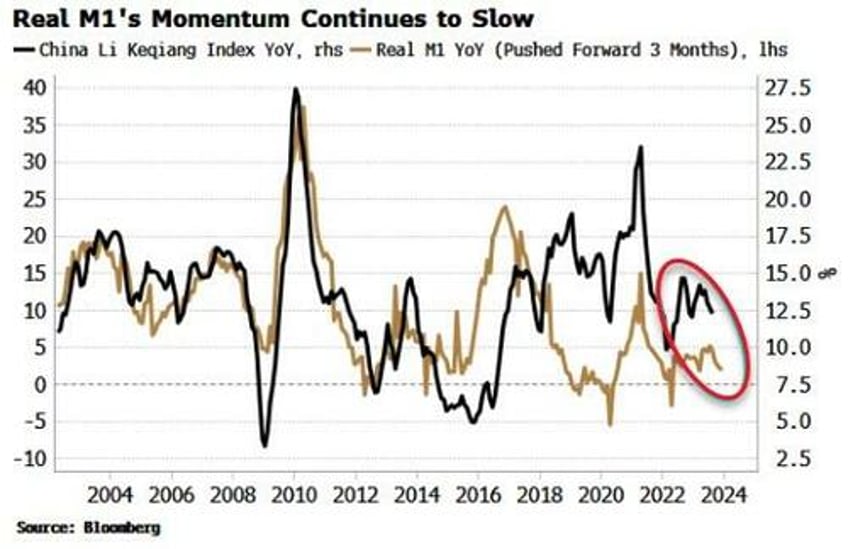

We’ve had a ream of data from China today, including money growth, inflation, and trade and loan data. Money growth is the key one to watch, specifically M1 growth. In real terms, it has historically led, by around six months, the cyclical ups and downs of the Chinese economy.

Growth in the measure, which includes central bank deposits and some other deposits, came in at an annual rate of 2.1% in September, down from 2.2% in August. When China is on the cusp of sustainable recovery, it will show up in M1 growth first. As the chart below shows, we’re not there yet.

Policymakers’ announcement earlier today that they are considering a new stabilization fund to prop up the stock market would need to increase liquidity in some way.

But muted real money growth has led excess liquidity (real money growth less economic growth) in China rolling over. This is a headwind for risk assets such as stocks.

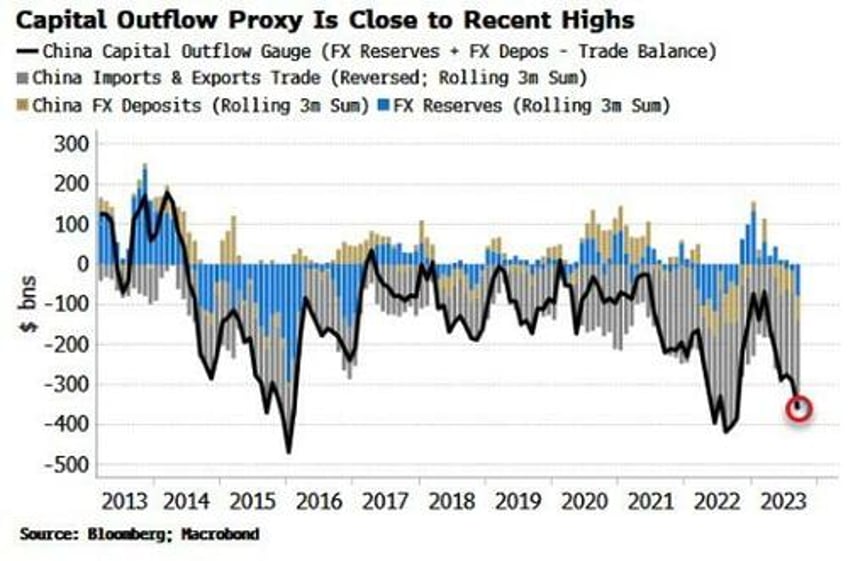

Liquidity in China is being weakened by capital outflow. Formally, the country has a closed capital account, but in reality, where there’s a will there’s a way (such as over-invoicing for exports), and capital will find a way to leave, especially when domestic growth is weak. When capital leaves, it causes domestic liquidity to tighten.

We can proxy for capital leakage by looking at the difference between the trade surplus and public (PBOC) and private FX reserves. On this measure, capital outflow from China is nearing 2022 and 2015 highs.

This is one reason to allow the currency to weaken. The yuan has fallen almost 6% versus the dollar this year (although it’s up slightly against the official FX basket). A weaker currency tempers the negative-liquidity impact of capital outflow.

Nonetheless, China has recently been pushing back on yuan weakness versus the dollar through setting its daily fixing an average of 12 or 13 big figures (i.e. 0.12 or 0.13) below the spot rate.

It depends on how long China can put up with stagnant growth and the threat of rising unemployment, but the longer incremental easing measures do not work and the stock market falters, it raises the chance a much larger stimulus bullet will be delivered. Sovereign bond issuance has been rising in a sign China is starting to tap the ample borrowing room of its central government to boost fiscal stimulus.