Bloomberg recently penned a great piece on the “Law of Unintended Consequences.” To wit:

“There is only one true law of history, and that is the law of unintended consequences. In the early 1920s, the University of Chicago economist Frank Knight famously drew a distinction between calculable risk and unknowable uncertainty. He overlooked a third domain: Unintendedness — where what happens is not what was supposed to happen.”

While the article focuses mainly on the rise in bond yields, it applies to several current market events. As is always the case, individuals are always looking for why “this time is different.” Not surprisingly, as discussed last week, the consequences of such thinking consistently lead to underperformance. To wit:

“Throughout history, whenever most investors believed the worst about a particular asset class, such has often been the right time to start buying. As we have often discussed, psychological behaviors account for as much as 50% of the reasons investors consistently underperform the markets over the long term.”

Behavioral biases lead to poor investment decision-making. Dalbar defined nine of the irrational investment behavior biases specifically:

Loss Aversion – The fear of loss leads to a withdrawal of capital at the worst possible time. Also known as “panic selling.”

Narrow Framing – Making decisions about one part of the portfolio without considering the effects on the total.

Anchoring – The process of remaining focused on what happened previously and not adapting to a changing market.

Mental Accounting – Separating the performance of investments mentally to justify success and failure.

Lack of Diversification – Believing a portfolio is diversified when it is a highly correlated pool of assets.

Herding– Following what everyone else is doing. Which leads to “buy high/sell low.”

Regret – Not performing a necessary action due to the regret of a previous failure.

Media Response – The media is biased to optimism to sell products from advertisers and attract view/readership.

Optimism – Overly optimistic assumptions lead to rather dramatic reversions when met with reality.

The biggest problems for individuals are the “herding effect” and “loss aversion.”

These two behaviors tend to function together, compounding investor mistakes over time. As markets rise, individuals believe the current price trend will continue to last for an indefinite period. The longer the rising trend lasts, the more ingrained the belief becomes until the last of “holdouts” finally “buy in” as the financial markets evolve into a “euphoric state.”

As the markets decline, there is a slow realization that “this decline” is something more than a “buy the dip” opportunity. As losses mount, the anxiety of loss begins to climb until individuals seek to “avert further loss” by selling.

Unsurprisingly, the consequences of emotional biases are the most negative at market peaks and troughs.

High Valuations, Rates & Low Volatility

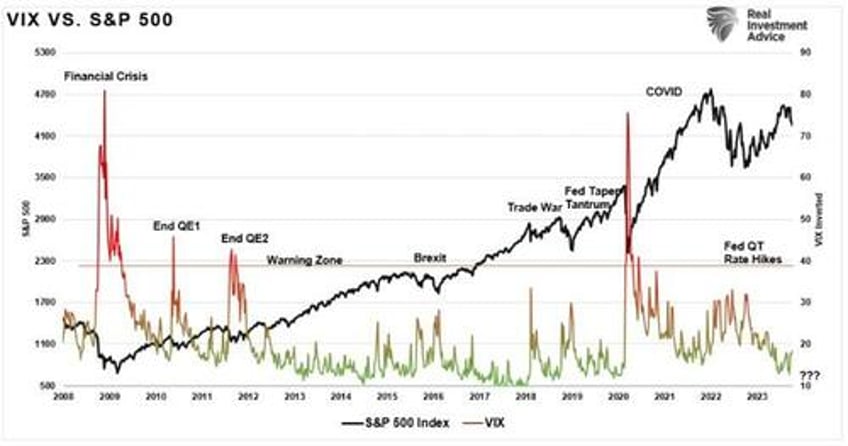

In 2023, the big story is the surge in interest rates. Higher borrowing costs impede economic growth, which ultimately reduces corporate earnings. Interestingly, investors are choosing to believe it’s different this time. Such is evident by higher asset prices and suppressed volatility.

At the same time, despite the consequences of higher interest rates, investors are willing to pay higher multiples for corporate earnings despite slowing economic growth rates. Historically, the consequences of overpaying for valuations in a rising rate environment have not been positive. However, in the short term, investors are often lulled into a sense of complacency, again believing this time is different.

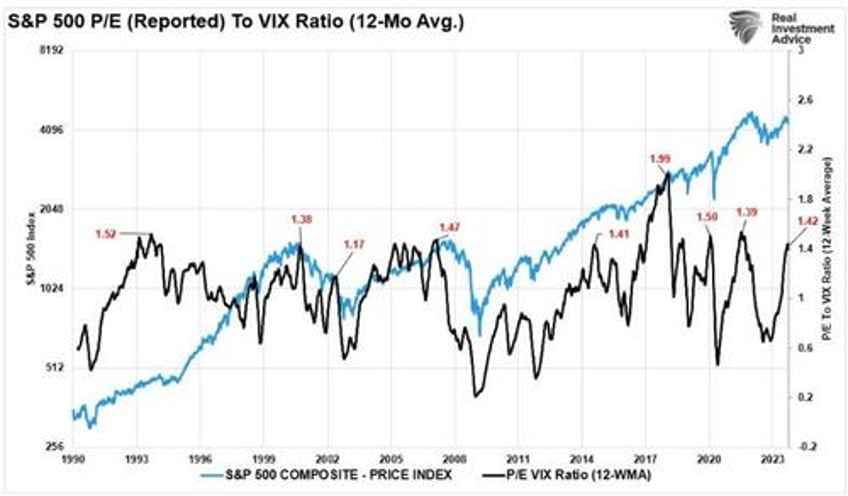

An interesting point was made on Twitter last week when I posted the following Valuation (P/E) to Volatility (VIX) ratio chart. The chart shows that when the ratio is elevated, such has often coincided with either more significant corrections or bear markets.

Unsurprisingly, I received the following comment.

Thomas seemed to forget the 20% decline in late 2018. However, suggesting that the indicator is “unreliable” over two historical instances is certainly hoping on the “this time is different” scenario.

At some point in the not-too-distant future, investors will likely discover the unintended consequences of overpaying for assets and ignoring risk in a high interest-rate environment.

As is always the case, “timing is everything.”

The Consequences Of Hope

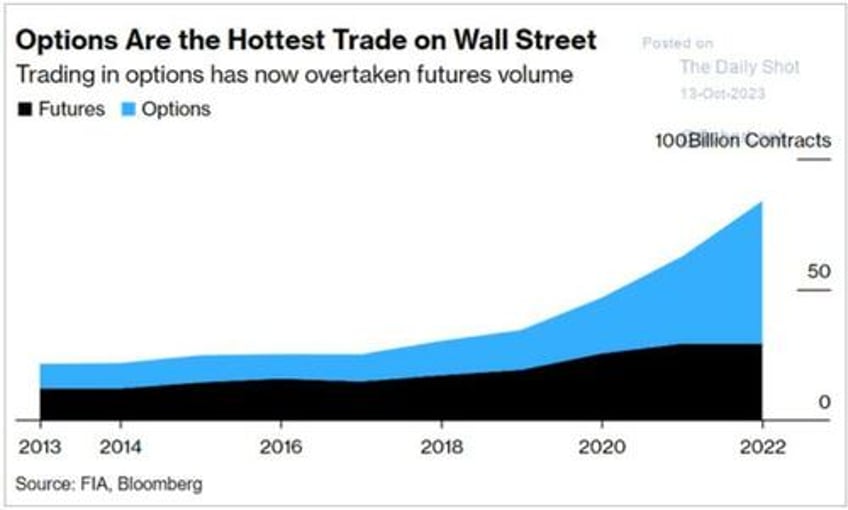

It is an exciting period that we live in currently. On one hand, a large contingent of investors hopes that stocks will continue higher indefinitely. Such is seen in the sharp rise in options trading over the last few years. Options and futures are some of the most speculative forms of assets as they have an expiration date.

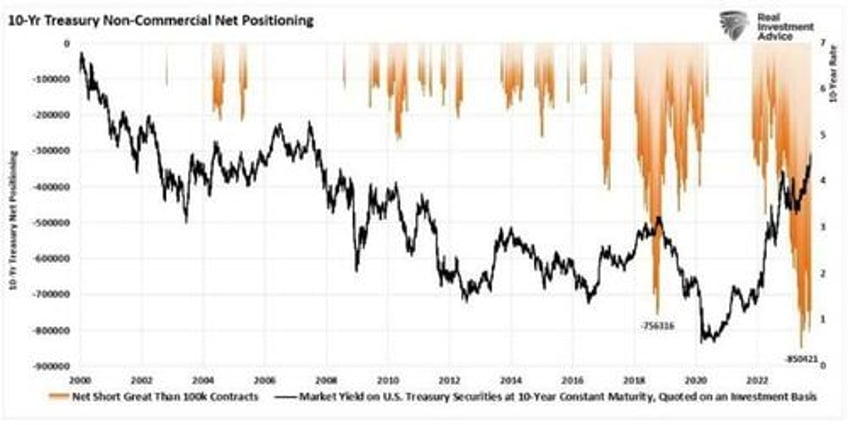

On the other hand, there is a significant “bearish” chorus betting on a continued bear market in bonds.

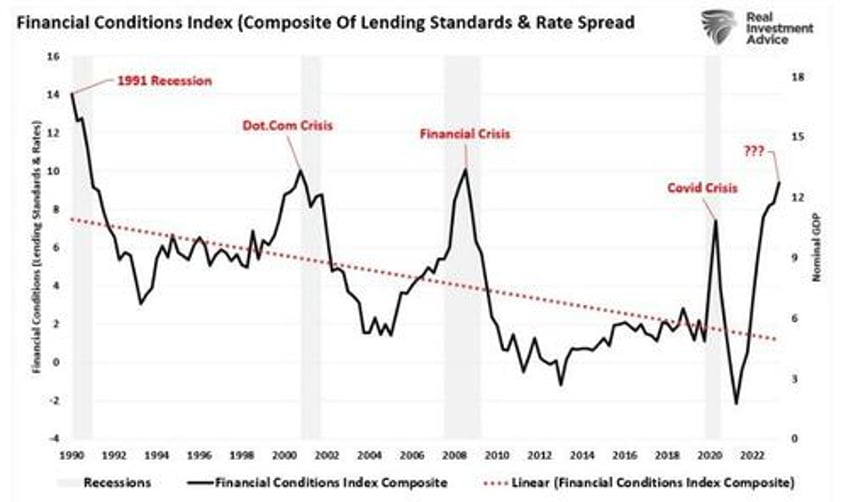

While each camp is betting on “this time being different,” it is unlikely that both will be right. The consequences of higher rates and tighter monetary policy are a drag on economic growth. As such, and unsurprisingly, such policies have always preceded economic recessions and financial events.

However, for those hoping for a “this time is different” scenario, one must believe the Government or the Federal Reserve can control outcomes to limit financial crisis events, bear markets, or recessions. In “The Unanticipated Consequences of Puposive Social Action” (American Sociological Review, 1936), Robert K. Merton proposed five possible reasons why the best-laid schemes of politicians and planners so often go awry:

Partial knowledge is “the paradox that, whereas past experience is the sole guide to our expectations on the assumption that certain past, present and future acts are sufficiently alike to be grouped in the same category, these experiences are in fact different.”

Error is “the too-ready assumption that actions which have in the past led to the desired outcome will continue to do so.”

The “imperious immediacy of interest” is the “instances where the actor’s paramount concern with the foreseen immediate consequences excludes the consideration of further or other consequences of the same act.”

“Basic values” are the “instances where there is no consideration of further consequences because of the felt necessity of certain action enjoined by certain fundamental values.” The example Merton gives is Max Weber’s Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism, where deferred gratification had the unintended consequence of accumulating capital and ultimately eroding Calvinist asceticism.

Self-defeating prophecy where the “Public predictions of future social developments are frequently not sustained precisely because the prediction has become a new element in the concrete situation … [so that] the ‘other-things-being-equal’ condition tacitly assumed in all forecasting is not fulfilled.” – Bloomberg

While this time may seem different in the short term, the unintended consequences of monetary polices have always manifested themselves in the long term.

This time is not different.