US fiscal policy is increasingly infringing upon the Federal Reserve’s independence, heightening already elevated secular inflation risks and condemning the dollar to an even deeper debasement in its value...

It was good while it lasted.

But the modern era of monetary policy independence is drawing to a close, with central banks reverting to their usual position of subservience to their fiscal overseers.

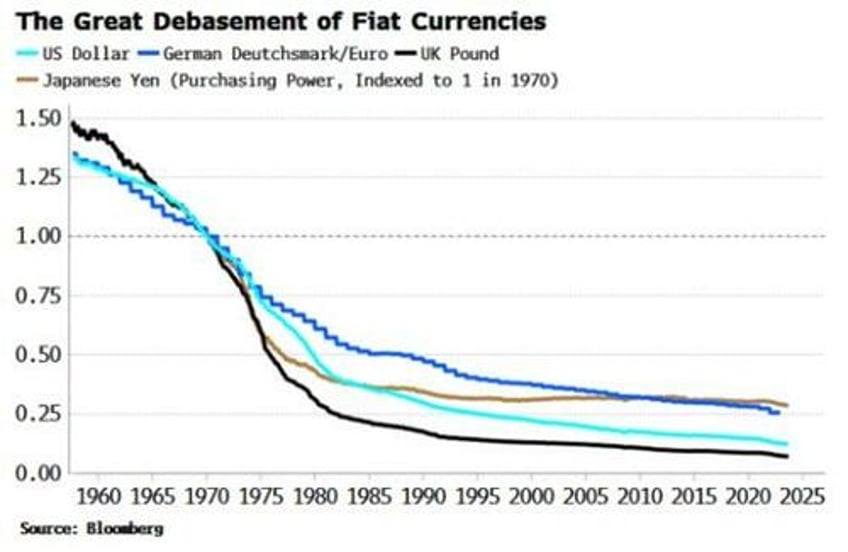

That’s a bad portent for fiat currencies, whose real value has already been decimated in the decades since the link with gold was fully severed.

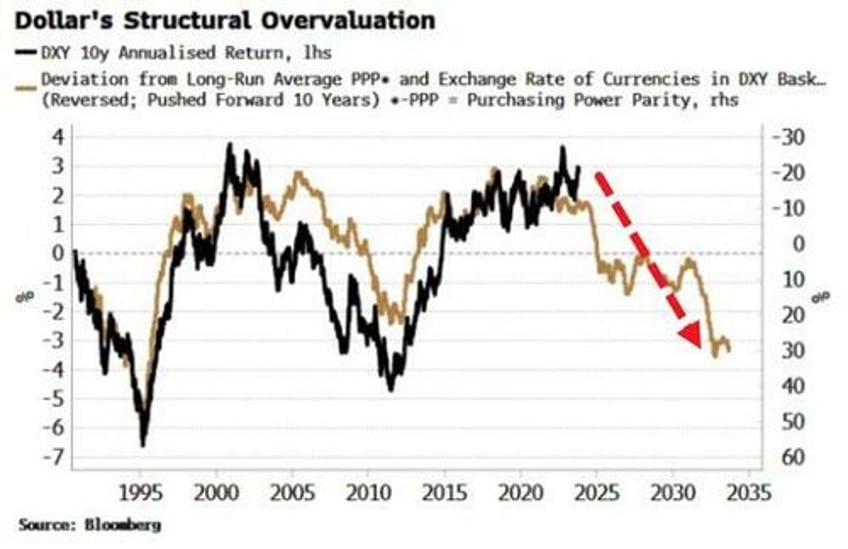

The exchange-rate value of the dollar has been rallying in recent months, but short-to-medium term leading indicators of the USD such as long-dated OIS show that, outside of a significant geopolitical-driven rally, it should soon begin trending lower again.

The dollar is also structurally overvalued. The chart below shows that the USD’s long-term growth rate will fall in the coming years if the currency follows its historical pattern and adjusts down to other DM currencies on an exchange-rate and purchasing-power-parity basis.

More relevantly for anyone who earns dollars, its real value is also fated to keep falling.

The dollar’s purchasing power along with several other major DM currencies has collapsed since the end of Bretton Woods in 1971, with the US currency buying barely a tenth of the goods and services it could buy you in 1970, and sterling only a fourteenth.

Unfortunately that trend is set to continue at an accelerated pace as governments increasingly encroach on monetary policy.

Fiscal dominance occurs when the size of government debt and deficits “dominate” the central-bank’s goal of keeping inflation in check. Equivalently, it happens when the central-bank’s maneuverability is circumscribed by the size and structure of the sovereign’s debt and borrowing needs.

The US is already some of the way there. Recent Fed comments have highlighted that the term-premium driven rise in longer-term yields will reduce the need for further rate hikes. Furthermore, fluctuations in the now large (+$800 billion) Treasury account at the Fed have a significant impact on liquidity.

None of this is much of an issue when the government is running fiscal deficits closer to their historical average. But the birth of the Treasury put has meant that what’s expected from governments, especially after the pandemic, has swollen greatly, and along with it sovereign spending and borrowing.

It’s similar in Europe, with an implicit acknowledgment of larger debt and deficits in new EU rules that will give countries greater flexibility in breaching the 3%-deficit and 60%-debt limits enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty (many countries are breaching them already).

The fiscal deficit in the US recently hit its widest peacetime, ex-recession level at 8.3% of GDP, while the debt-to-GDP ratio has risen to 129%, from 107% in 2019. The Treasury put means that debt and deficits are likely to remain elevated for the foreseeable future.

With such large financing needs, central banks rigidly trying to enforce an arbitrary inflation target become a nuisance.

Needs must, and central banks - already experiencing a chipping away at their de facto independence - will see its further erosion and, possibly, its eradication eventually in all but name.

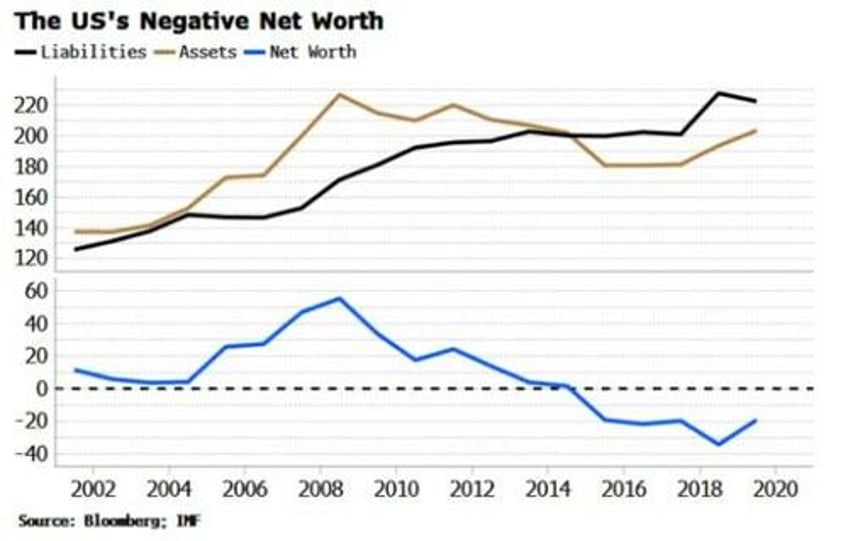

Large fiscal deficits are compounded by the dismal net-worth positions of many DM countries. The IMF attempts to calculate each country’s total assets and liabilities. Assets include buildings and land owned by the government, while debt is only one part of liabilities, which also include public-sector pension obligations.

The US’s net worth – total assets minus liabilities – is now firmly negative, at ~20% of GDP. Germany, Italy, France, the UK and Japan also have negative net worths.

DM countries’ fiscal positions will become further constrained from growing health and social-security costs. Central-bank independence stands little chance as governments borrow hand-over-fist to try to make up for expanding revenue shortfalls.

This is inflationary. As Charles Calomiris of Columbia Business School puts it: “Every major inflation in world history is a fiscal phenomenon before it is a monetary phenomenon.” When the public is no longer willing to fund the government (auction failure), governments move to fund their deficits with non-interest bearing debts, aka printing money.

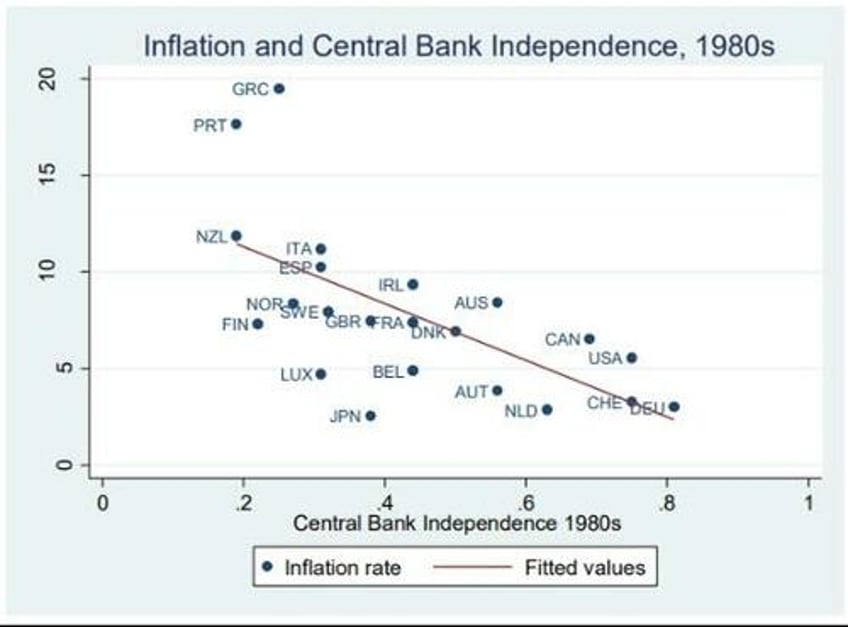

The Kennedy School at Harvard in a paper from 2018 found that from the 1970s to the 1990s there was a significant negative relationship between central-bank independence and the level of inflation, with less independent central banks associated with higher inflation.

Kennedy School, Harvard University

The likelihood the current bout of global inflation will be transitory as governments reclaim their dominance over monetary policy is becoming vanishingly small.

A secular rise in inflation in the US promises to further debauch both the purchasing-power and exchange-rate value of the dollar.

Said Keynes, “by a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate … an important part of the wealth of their citizens”.

As the Fed becomes an instrument of the government, the quality of the assets on its balance sheet will progressively worsen. That will happen either through owning ever more government debt of deteriorating quality through yield curve control-like policies; or from having to periodically backstop a system prone to more frequent financial crises in an elevated-inflation and high-rate vol environment (e.g. SVB in March of this year).

The dollar is but a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet.

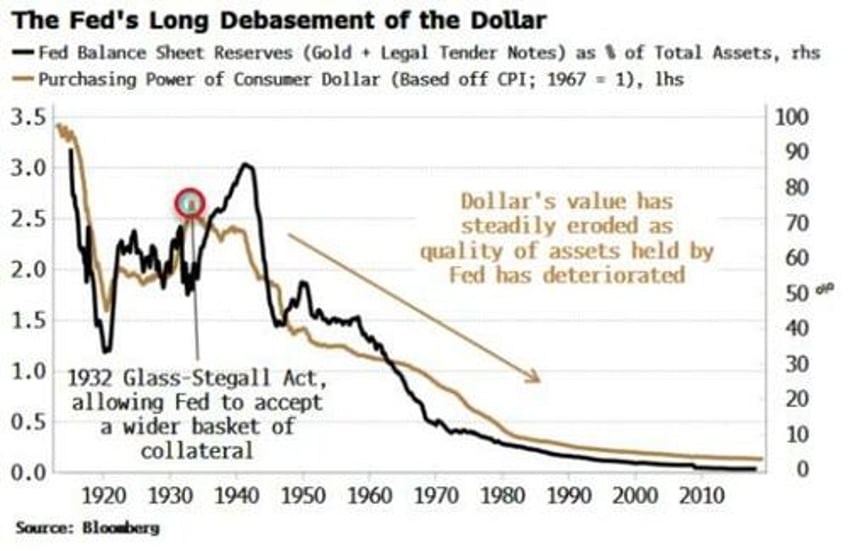

Before the Glass-Steagall Act of 1932, which allowed the Fed to borrow against a broader range of collateral, its balance sheet consisted mainly of gold.

As its size has mushroomed over the decades, it has also deteriorated in quality, consisting of more assets of a riskier nature (the Fed was willing to buy high-yield corporate debt during the pandemic), while the proportion of gold held has fallen to near zero.

That trend is set to continue as the balance sheet increasingly becomes subservient to the government’s borrowing needs, leaving the dollar facing no escape from its multi-decade debasement.