At a time when mainstream economists and FOMC policymakers are betting the farm on a "soft landing" for the US economy, an unexpectedly hard signal was just issued by none other than the Fed itself: for the first time in over a decade, the US central bank announced it would cut about 300 people from its payroll this year, a rare reduction in headcount for an organization that has grown steadily since 2010 - after all, it takes if not a village (with its own police force), then certainly thousands of workers to come up with catastrophically wrong economic forecasts and to keep the money printer primed and ready to pump out a few trillion at a moment's notice.

A Fed spokesperson said the cuts are focused on the staff of the Fed's 12 regional reserve banks and mainly hit information technology jobs, including some no longer needed because of the spread of cloud-based computer software, and positions connected to the Fed's various systems for processing payments, which are being consolidated. The staff cuts represented a combination of attrition, including retirements, and layoffs.

You learned to code? Now learn to cook.

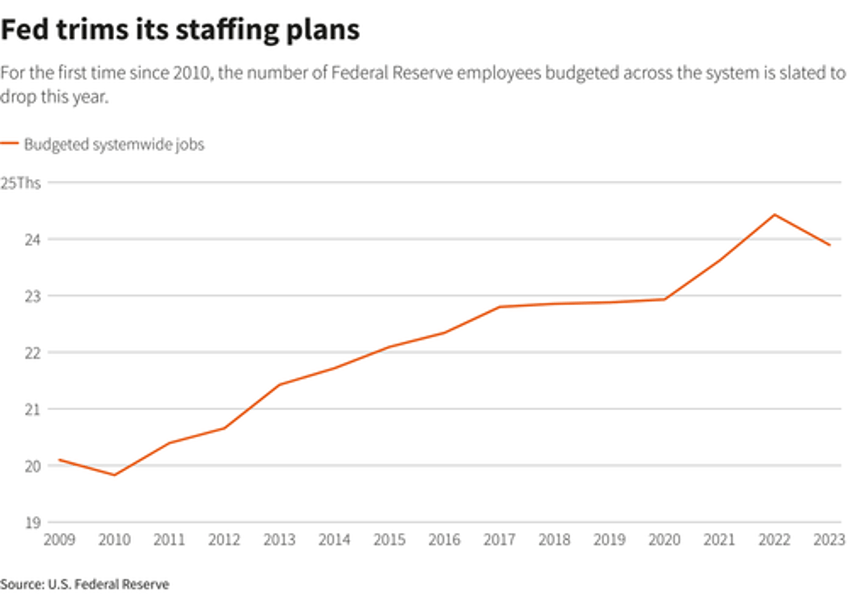

Reuters writes that according to annual reports and financial documents prepared by the Fed each year, the number of staff budgeted for the system, including its regional banks, the Washington-based Board of Governors, and three smaller units, is due to fall by more than 500 positions from 2022 to 2023, from 24,428 to 23,895.

And while small compared to the size of the Fed, it is the first time budgeted headcount has fallen since 2010.

Since actual employment in 2022 fell below budget - a December Fed memo cites "higher than-budgeted turnover and extended lags in filling open positions," notably in the area of bank supervision, as the reason - the number of positions being eliminated this year is somewhat smaller than the budgeted decline.

While the December memo from the Board of Governors division that oversees the regional reserve banks does not explicitly call for staff cuts, it highlights the need to stick with internal budgeting protocols, "with the most important focal points being alignment with long-term strategy and stewardship of public funds."

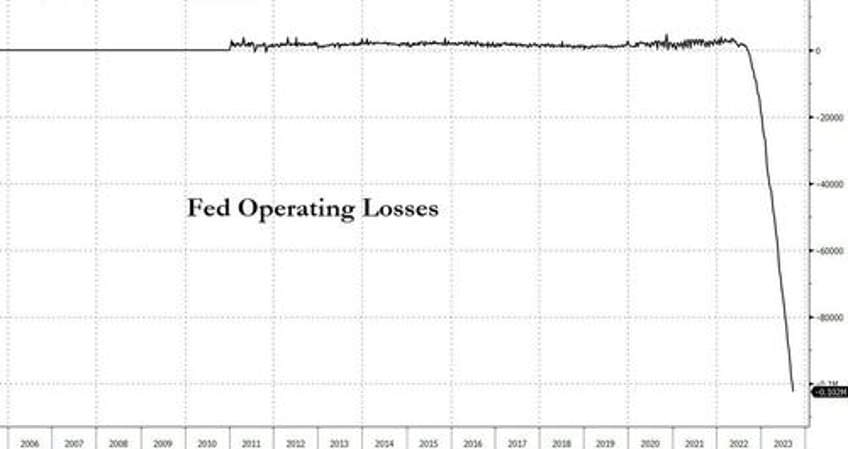

The staff reductions are happening at a sensitive time for the Fed. It has booked $100 billion in losses in recent months on operations that currently involve paying more in interest to banks on reserve deposits at the Fed than the central bank earns from its roughly $7.5 trillion portfolio of bonds and mortgage-backed securities.

Unlike federal agencies that spend tax dollars allocated by Congress, the Fed is self-funding. Its earnings from its asset holdings and fees charged to banks for a range of services are used to pay the roughly $6.3 billion in annual expenses of a system that employs nearly 24,000 people in Washington and other cities across the country.

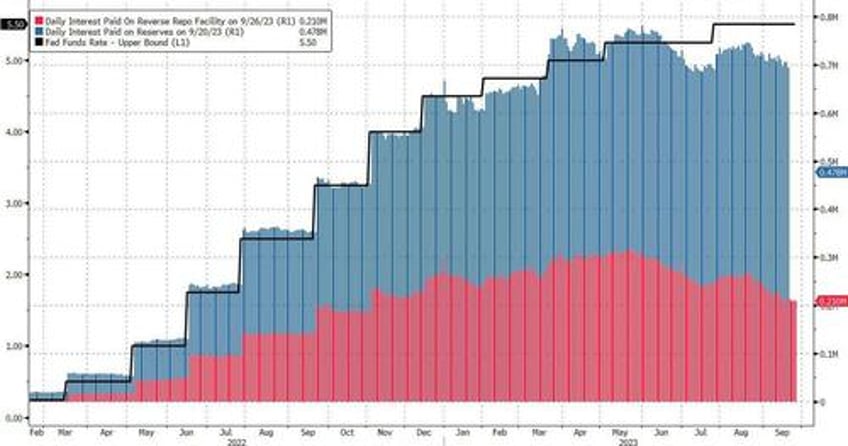

In most years the Fed generates a profit that is turned over to the U.S. Treasury. But since the central bank began to increase interest rates to control a surge in inflation, it has been spending more than it earns each year, and in effect gives the Treasury an IOU to be paid later. Most recently, the Fed was paying out over $700 million each day between interest paid on Reverse Repo and Reserves.

While the staff cuts are not directly tied to the Fed's losses, the central bank's operations have been under scrutiny among Republicans in Congress who have expressed concern about how deeply the Fed was delving into issues, like climate change and the economics of inequality, that seemed to them to be beyond its monetary policy and bank supervisory missions.

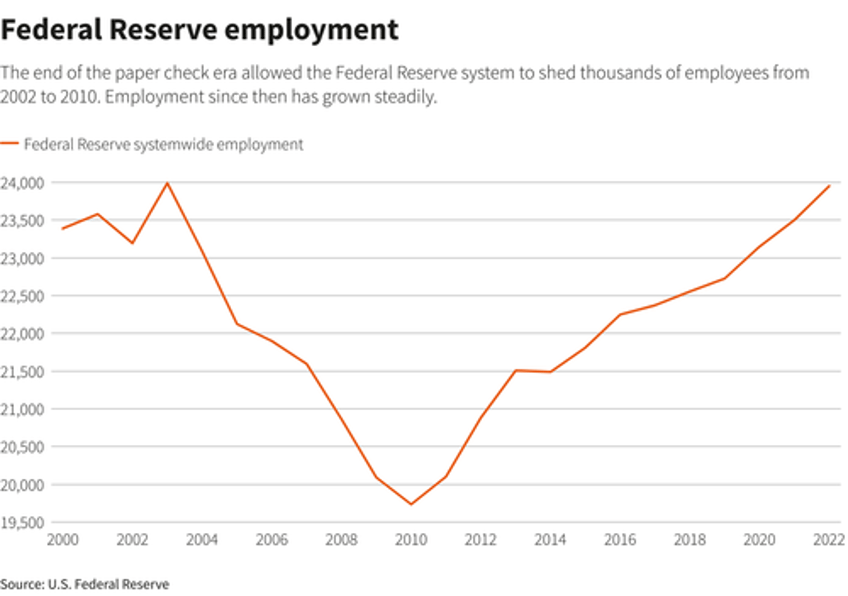

The number of system-wide jobs at the Fed had been falling earlier this century, from just shy of 24,000 as of 2003 to 19,735 as of 2010, as the end of the paper check era allowed the Fed to trim the legions of workers it took to clear and process those documents.

Since then, the Fed has unleashed the biggest balance sheet expansion and monetary experiment in history, and it now appears that creating all those imaginary, digital trillions in reserves was very labor intensive, pushing the Fed's workforce back to all time highs.