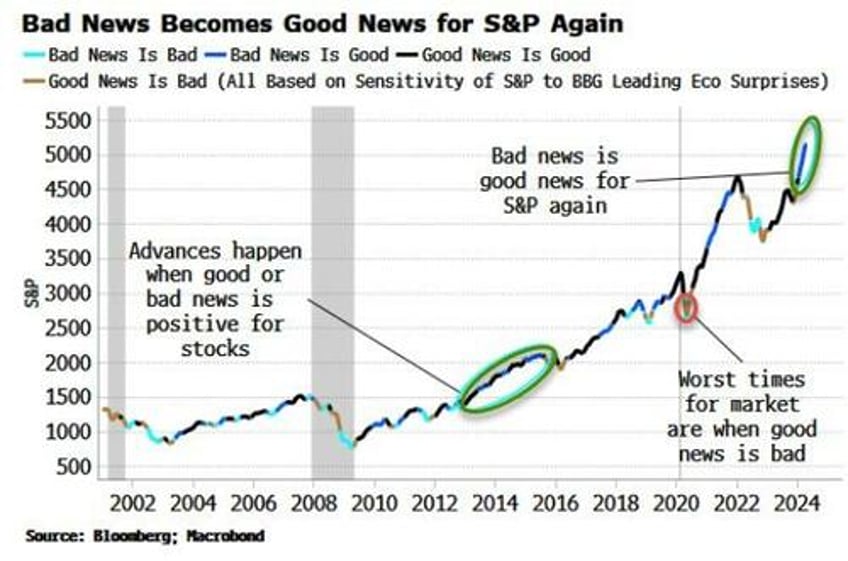

We’re back in a “bad news is good news” regime for stocks, where weak economic data prompts higher prices. That’s typically a supportive backdrop for equities, but investors should be alert for when stocks fail to rally on good news as this signals the economy is potentially in or about to be in a recession, with the stock market poised to see its worst returns.

“Bad news sells best. ’Cause good news is no news,” says Kirk Douglas’s journalist in Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole. But bad news isn’t just a boon for newspapers; stocks also frequently rally on news that intuitively should see them selling off.

Blame central banks for this perverse state of affairs, with their implicit backstop for markets.

Stocks have recently been rallying on the back of weaker economic data points, such as payrolls and the ISM.

But the “bad news is good news” shorthand used by the market needs a more rigorous foundation.

First, define exactly that we mean by statements like “bad news is good news”;

second, define the different regimes based on our definition;

and third, look at how the market has performed through the regimes.

Claude Shannon - the father of information theory which forms the basis of modern communication - invented the idea that information is surprise. The utility in information comes not from what is expected, but what is unexpected. That’s typically how markets behave with economic data, reacting not to the information itself, but by how much it surprises to the upside or downside.

Economic surprise indexes capture the number of surprises on a cumulative basis. When they are positive, economic data is on net beating expectations, and vice-versa when they are negative. Therefore we can define four regimes based on how stocks are changing in relation to economic surprises:

Good news is good news (stocks and eco surprises rising together)

Bad news is good news (stocks rise when eco surprises fall)

Good news is bad news (stocks fall when eco surprises rise)

Bad news is bad news (stocks fall when eco surprises fall)

I have used the Bloomberg surprise indexes, which are separated out by economic type, such as survey data and labor data. I took the median of these indexes, excepting those that have a negative relationship with the S&P over the whole sample period (we would expect a positive relationship overall, e.g. positive surprises causing the market to rally).

The chart above shows the S&P color-coded for the different regimes. As we can see, the market not long ago went back into a bad news is good news regime. Most of the S&P’s advance since October 2022 has either been in that regime, or the good news is good news regime. These two are typically dominant when the market is in a strong bullish trend – no wonder when stocks go up on good or bad news!

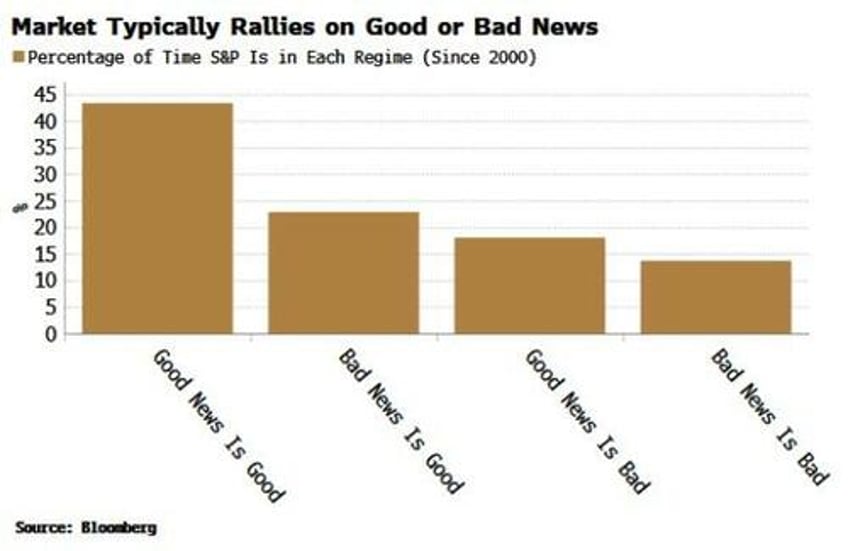

There’s no significant difference if we restrict the sample to the post-GFC period when Federal Reserve support for markets became more explicit, with the percentage of the time when bad news was good for stocks only rising marginally to 26% from 23%.

The market rallying on any news is what you would expect to see more often, given that the market generally rises over time. But if there were no Fed it’s a strong bet that stocks would rise less of the time overall as they would not be as insulated from bad news.

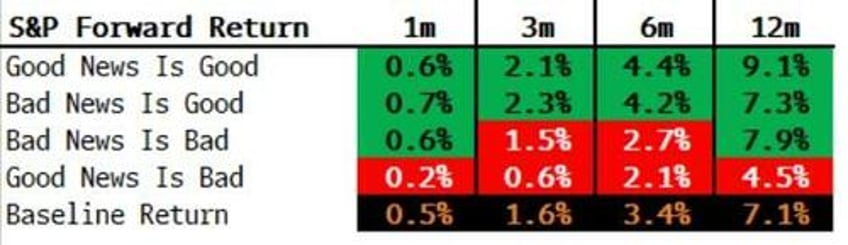

This is all quite interesting, but what does it tell us about stock performance? The table below shows the one, three, six and 12-month average forward returns of the S&P when in each regime, along with the whole-sample average returns for the same time periods.

We can see when stocks are rallying on good or bad news (top two rows in table), forward returns on all time horizons are above average. Thus the current regime is historically consistent with the S&P returning a little above its average over the coming months.

When stocks are selling off on bad news, that’s not great for forward returns, but when stocks can’t even rally when the news is good is when investors need to be most wary (bottom row in table).

It is in this regime that stocks consistently come in below average, performing poorly over the next one, three, six and 12 months.

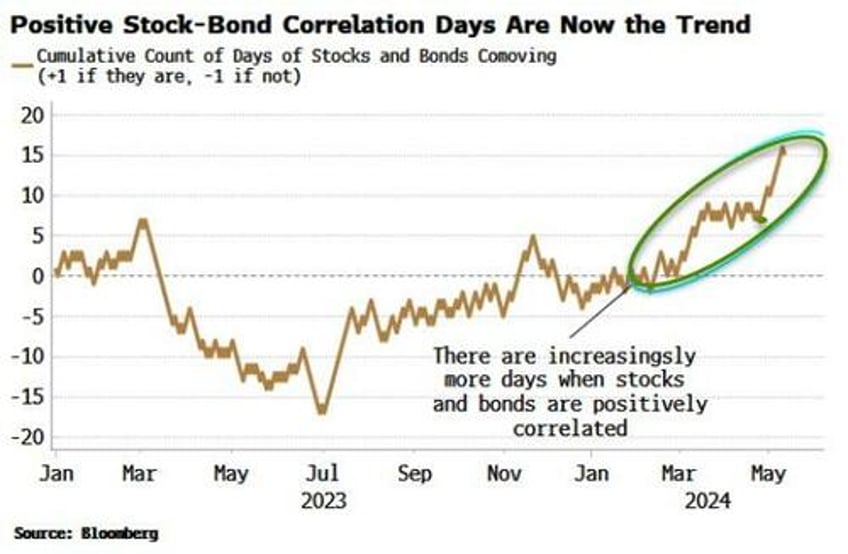

By what avenue does disappointing data cause stock prices to rise? One way is bad data triggering a flight-to-safety bid in bonds, or a lowering in Fed rate expectations, and the resulting lower yields boosting stock prices. We find that this “bad news is good news” regime is more likely when the stock-bond correlation is positive (on a rolling one-year basis) versus when it is negative.

But that’s not the only way. Positioning can mean stocks can rally as investors sell the rumor of weaker-than-expected data, and then buy the fact when the data comes in.

Nonetheless, in the current environment there are more days when stocks and bonds are positively correlated versus when they are not, increasing the likelihood the bad news is good news dynamic can persist for now.

That will help stocks as they face potential headwinds from an economy that may soon begin to look more recessionary. Unsurprisingly, during recessions even good news is bad for stocks, and it’s best to be out of the market altogether.