In the run-up to Nvidia’s earnings release late Wednesday, there was a palpable concern in the market that the AI boom’s flagship would disappoint lofty expectations; what is now Wall Street’s most heavily traded stock traded -2% down during the afternoon session. And then Nvidia did it again, exceeding expectations in terms of revenue, earnings and forward guidance. The stock promptly jumped 9% in after-hours trading, which helped to lift Nasdaq futures by 1.5%. And the bullish sentiment spread to Asia Thursday morning, where after a 34-year wait Japan’s Nikkei 225 finally edged above its December 1989 record high.

With the terminals a sea of green, the obvious question for investors is the one Louis raised a couple of weeks ago—will markets in general, and US growth stocks in particular, continue to Party Like It’s 1999? Or are we heading for a 2000-style crunch?

Put differently, will a good story be overcome by bad valuations?

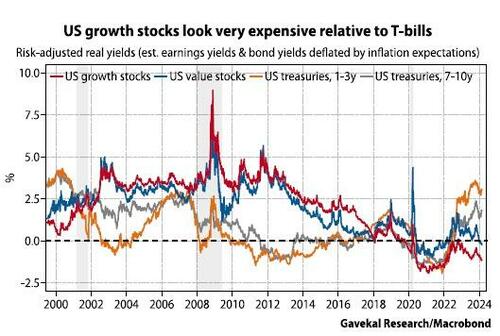

In the late 1990s, the story was that the internet was going to generate exceptional earnings growth for companies in tech, media, and telecoms. The TMT bubble inflated until by early 2000 the prospective earnings yield on US growth stocks was pitiful, both in absolute terms and when compared to the real yields in US fixed income (whether bonds or bills). Eventually, the valuation gap became too great and the market started to have doubts about when clicks would be converted into revenues, and the bubble burst. Investors fled growth stocks for fixed income, with growth stocks losing a quarter of their value in 2000, while bonds rallied. By the end of the year, risk-adjusted real yields on the two asset classes had largely converged (see the chart below). Meanwhile, value stocks, which never got anything like as overvalued, were flat for the year. It was not until the US recession began in March 2001 that value stocks joined the sell-off.

Fast forward to today and the relative valuation story is similar. Equities are generally expensive relative to fixed income. But the biggest gap is between growth stocks and short-term US treasuries.

Given this valuation spread, a continuation of the current rally in US growth stocks likely depends on one or both of the following:

(i) earnings continue to exceed expectations;

(ii) the Federal Reserve cuts rates and real bond yields fall—with no recession.

Either is possible.

On the earnings side, the strong recent economic data helps. January saw impressive payrolls growth and a pick-up in PMIs (February PMIs are out on Friday and will be worth monitoring). It is also encouraging that the leaders of this boom—Nvidia, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta etc.— have seen strong revenue and earnings growth, not just click growth. The balance sheets of these companies are also generally stronger than the balance sheets of the TMT bubble leaders, with less leverage and more cash. And as Louis has pointed out, unlike 1999-2000 there is little IPO activity today to leach away the liquidity supporting the stocks of the market leaders.

One big question is whether final demand for generative AI grows by as much as expected. Currently, Nvidia cannot make chips fast enough to meet the demand of its customers, and specifically of its four biggest customers— Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Meta—which account for 40% of its revenues. So long as final demand for generative AI continues to grow rapidly, these customers will likely continue to demand more chips from Nvidia and others, even as they are all developing their own AI chips. But if final demand for generative AI disappoints, today’s AI investment boom could result in overcapacity.

On the inflation front, the risk is that January’s uptick in US CPI and PPI inflation, along with the year-to-date rebound in oil prices, is not just noise but the start of a reversal from last year’s disinflationary trend. This is the subject of intense debate within Gavekal. From my perspective, I still believe the balance of evidence suggests inflation will remain benign.

But any more upside surprises in the inflation data will make the Fed more cautious about the timing and pace of rate cuts, because inflation remains the principal consideration determining Fed policy. If the Fed keeps short rates elevated while continuing quantitative tightening, the relatively high real yields on bonds and especially on bills could begin to weigh on US growth stocks. If inflation surprises on the upside, and the Fed confounds expectations for rate cuts, “T-bill and chill” will likely prove the investment strategy of choice.

The macro outlook for growth and inflation is always uncertain, and today is no exception. A continuation of the recent “soft landing” or “disinflationary boom” scenario is quite possible. The potential of generative AI appears great.

But given the extreme valuation gap between T-bills and growth stocks today, as in 2000 it is probably wise to take some profits on US growth stocks, and to buy more attractively-valued US value stocks, cheaper markets such as Brazil or China, or simply to load up on US T-bills.