Rates markets have begun to accept the higher-for-longer mantra from central bankers. But it may soon come undone if economies are nearer to recession than surface data implies.

Central bankers at last week’s Jackson Hole symposium did nothing to disabuse the notion that their intention is to keep interest rates elevated for an extended period.

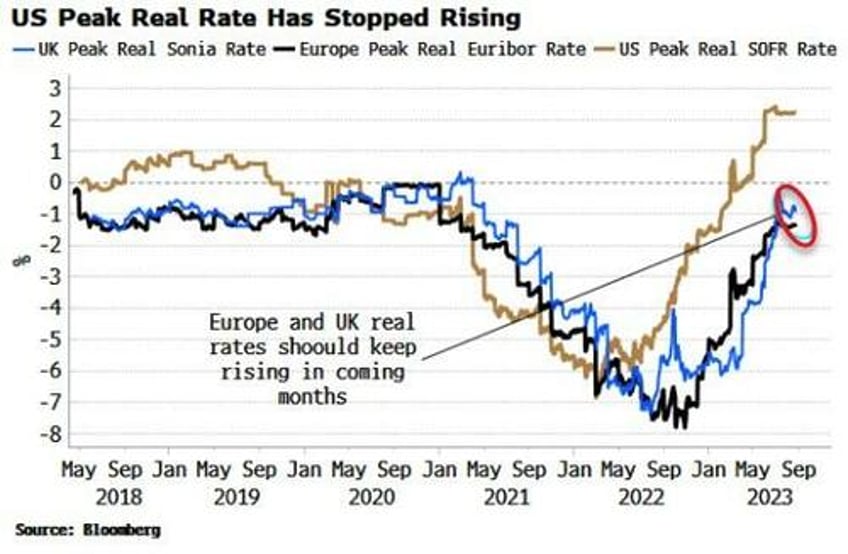

In the US, the real peak SOFR rate has remained over 2% since June. Short-term real yields are also historically elevated, with 2yr TIPS yields close to highs going back to 2004 (outside of their GFC spike).

Real rates in the UK and Europe are fast catching up to the US, but remain below zero. Indeed, based on where expected short rates and CPI fixing swaps are, the real policy rate of the both the BOE and the ECB will be positive by October.

The ECB’s real rate is expected to then remain around +1%, while in the UK it is expected to keep rising to well over +3% in the first half of next year. In the US the real rate is expected to remain at 2-3% over the next 12 months. The market is buying the higher-for-longer mantra for now.

But such tight conditions are about to collide with more recessionary-looking economies, testing central bankers’ resolve to keep rates elevated. Poor PMIs in Europe and the UK are a reminder that economies are very fragile. The problem with growth being so near to zero is that it doesn’t take much for the economy to be flipped into a recession.

Recessions happen suddenly, and typically when things look superficially OK.

Take the US.

Soft-landing talk is rife, but there are a number of reliable indicators that continue to be consistent with a near-term recession.

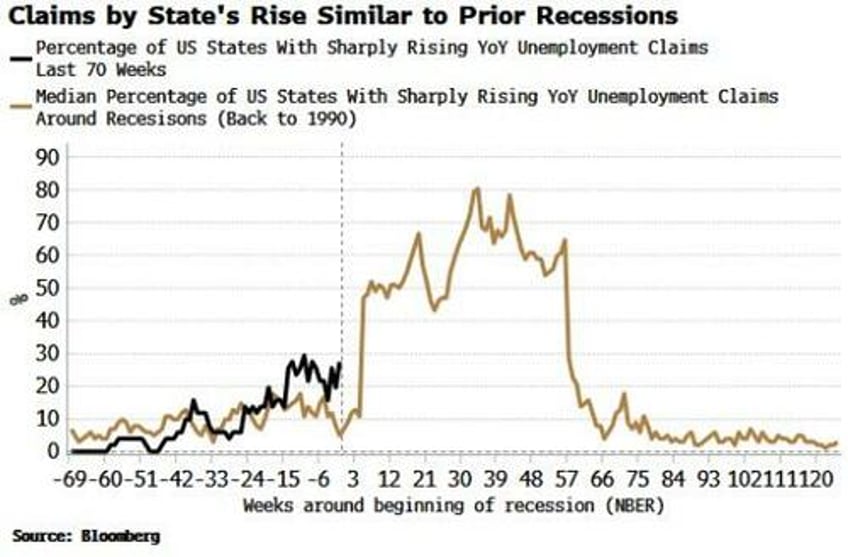

The chart below shows the percentage of US states with unemployment claims rising sharply on an annual basis for this year, and the median over recessions going back to 1990. The path for the last year or so (black line) is similar to the recessionary path (brown line).

That’s not to say a recession is a shoo-in. But such an indicator should also not be dismissed as it a) captures the pervasive nature of recessions (things get bad in lots of places at the same time); and b) it captures their phase-shift nature (things look fine…until they don’t).

Ironically the Fed at al may have to jettison higher-for-longer right at the time they have managed to get its message across.