By Dhaval Joshi of BCA Research

Summary:

The markets have been celebrating the killing of inflation without the killing of the economy, but they have popped the champagne corks prematurely.

Disinflation to date has been benign because it has come almost entirely from improving supply.

But the supply-side tailwind has exhausted, so the last mile of the journey to

2 percent inflation will be the hardest.

Our bullish structural stance on bonds is intact given Powell’s commitment that “we’re not declaring victory at all at this point, we think we have a ways to go.”

But tactically the bond rally went too far too fast, warranting a neutral stance.

If bonds consolidate, stocks are likely to consolidate too, also warranting a tactically neutral stance.

The markets, and the Wall Street commentariat, have been popping the champagne corks. They have been celebrating the killing of inflation without the killing of the economy. Yet this celebration is premature, at least in the US and the UK.

Through a simple sequence of charts, I will demonstrate that though the journey back to a sustained 2 percent inflation is possible without killing the US economy, it is not yet mission accomplished. The hardest part will be the last mile. I will then make a brief comparison with the UK and Germany.

Markets Have Popped The Champagne Corks Prematurely

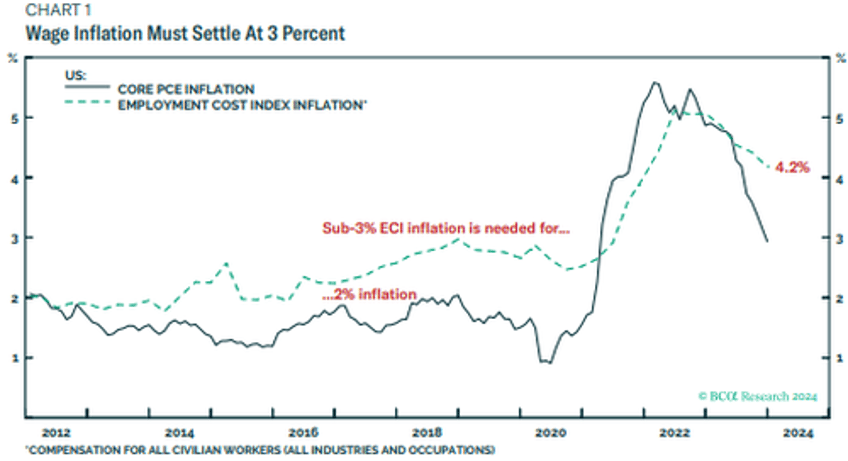

The first chart in the sequence shows that to return US inflation to a sustained 2 percent, wage inflation must return to 3 percent – which is still way below the current 4.2 percent, as measured by the latest US employment cost index (ECI).

Admittedly, over a shorter 6 months and 3 months, wage inflation is running at 3.9 percent and 3.5 percent respectively. But Jay Powell rightly counters that, given shorter-period inflation’s volatility and reliance on error-prone seasonal adjustments, “we need some confirmation that inflation is, in fact, coming down sustainably…” Which is why “12 months is our target.”

Another argument I hear is that the 1 percent gap between wage inflation and price inflation can be higher than its pre-pandemic average if productivity growth has gapped higher. But Powell correctly counters that this would be a dangerous presumption. Productivity growth will likely “shake out to back where we were (pre-pandemic).” Assuming this is true in other advanced economies, wage inflation must settle at 3 percent in those economies too.

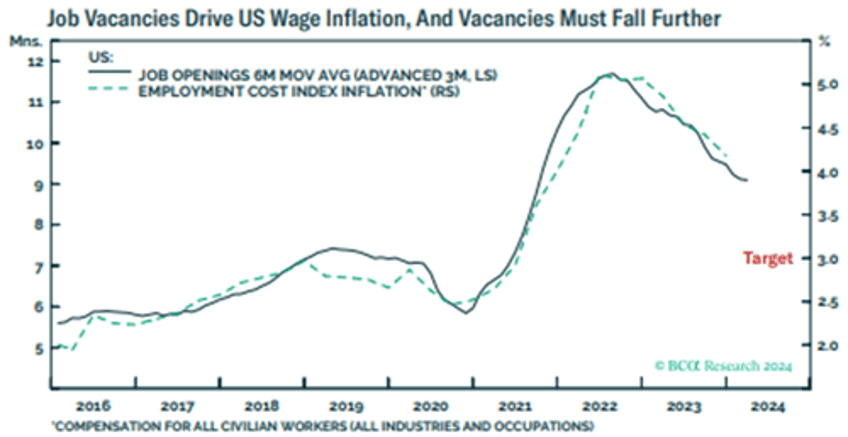

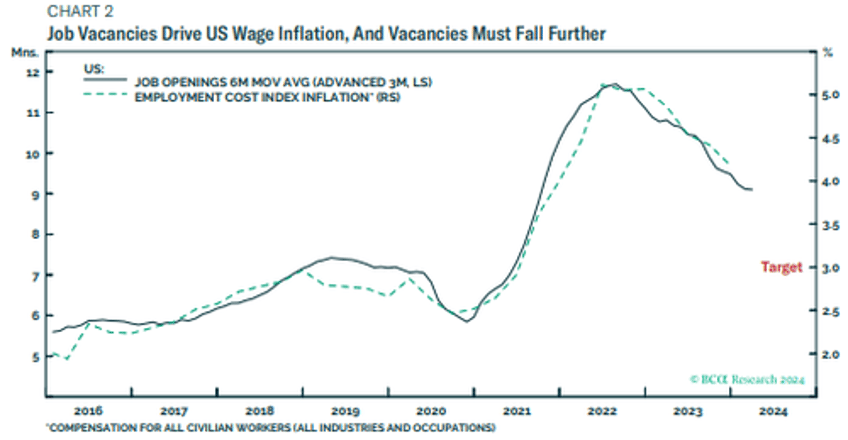

This brings us to the stunning second chart. For the past decade, the near-perfect driver of US wage inflation is simply the number of job vacancies.

The stunning simplicity of this chart makes perfect sense. By definition, a surplus of job vacancies reflects an excess demand for workers versus their supply, while wage inflation reflect the marginal price of workers. So, when the demand for workers far exceeded their supply, wage inflation surged. Then as the labour market rebalanced, wage inflation eased.

The important takeaway from this stunning chart is that vacancies need to come down further to achieve a sustainable 3 percent wage inflation and 2 percent price inflation. As Powell puts it, “although the jobs-to-worker gap has narrowed, labour demand still exceeds the supply of available workers.”

The Recovery In Labour Supply Caused The Benign Disinflation…

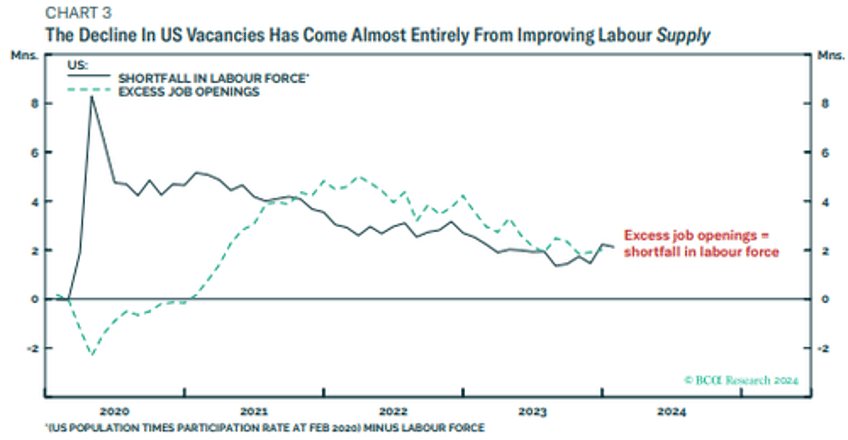

The third chart gets to the crux of our analysis. The imbalance in the US jobs market and its subsequent rebalancing – causing the surge in wage inflation and then a benign disinflation – has been almost entirely about labor supply.

We know this because, in 2021, when the economy reopened, the surge in the number of job vacancies precisely equalled the shortfall in the labour force that came from the collapsed participation rate. Likewise, the subsequent decline in vacancies through 2022-2023 has numerically tracked the declining shortfall in the labour force that came from a recovering participation rate.

As Powell puts it:

“We lost several million workers at the beginning of the pandemic from people dropping out of the labour force. And then when the economy reopened in 2021, you had a severe labour shortage and it was everywhere. But then, labour force participation came back strongly in 2023, and so did immigration. And those two (supply-side) forces have considerably lowered the temperature in the labour market.

…But The Benign Disinflation Has Run Its Course

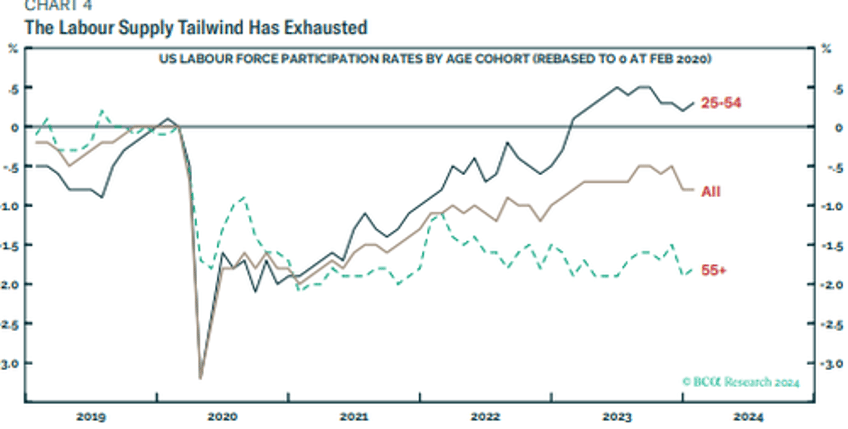

The fourth chart reveals the story’s denouement. The benign supply-side force – and the associated ‘immaculate disinflation’ – has run its course. The participation rate of prime aged (25-54) workers is now above the pre-pandemic level and topping out. Meanwhile, the participation rate of older aged (55+) workers remains stuck well below its pre-pandemic level reflecting the cohort of older workers who have permanently left the labour force. Meaning that the total participation rate is levelling out, below the pre-pandemic level.

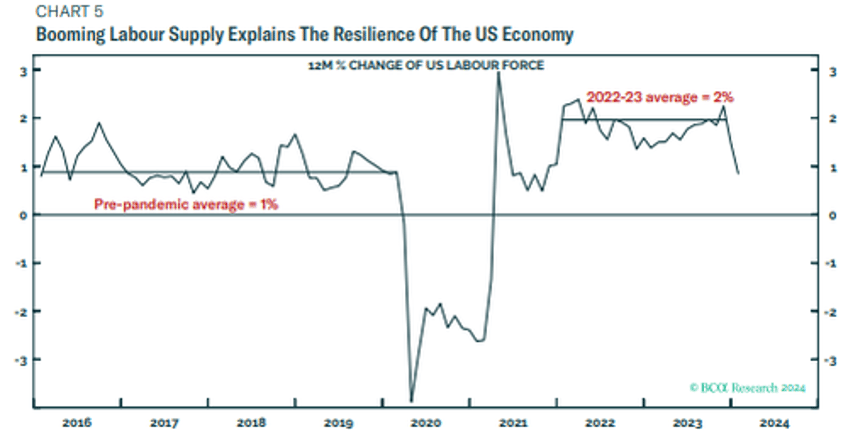

All of this also solves a puzzle that has been perplexing many economists. How has the US economy remained so resilient in the face of much higher interest rates?

The fifth chart provides the answer. Fuelled by the strong rebound in participation through 2022-23, the labor force grew at a heady 2 percent clip.

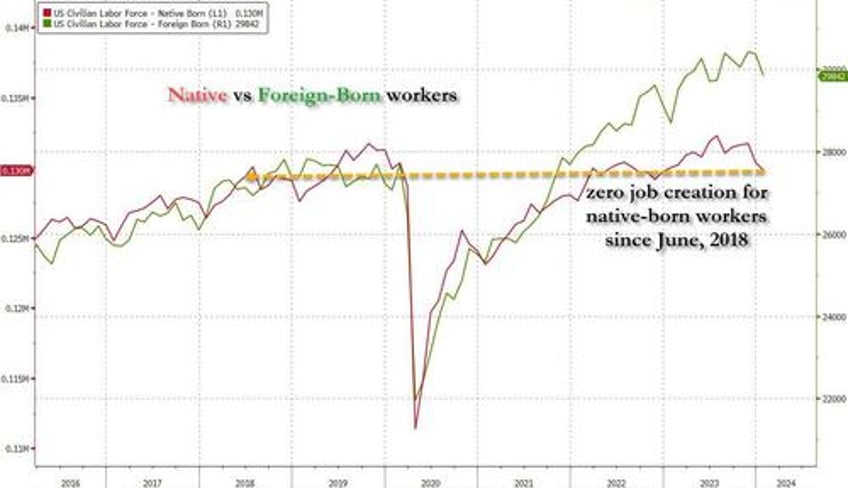

If we add in the unprecedented surge in illegal migrant workers who have crossed the Southwestern border, the true rate is likely closer to a blockbuster 3 percent.

Simply put, if the number of workers is growing at 3 percent, it is impossible for the economy not to show resilient growth! Even in the face of higher interest rates. To repeat though, this powerful supply-side tailwind is exhausted.

If the last mile of labour market rebalancing cannot come from a benign increase in participation, then there are three possibilities: It must come from a further increase in immigration – legal or illegal – which is political dynamite. Or, it must come from a malign decrease in labour demand, meaning a downturn, which is also political dynamite. The third possibility is, as Powell says, “that inflation would stabilise at a level meaningfully above 2 percent.” This would be politically easiest, but risk destroying the credibility of the central bank.

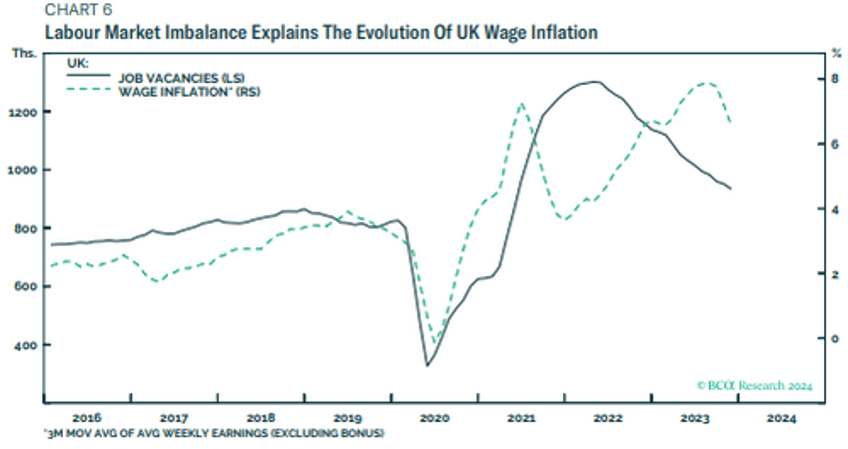

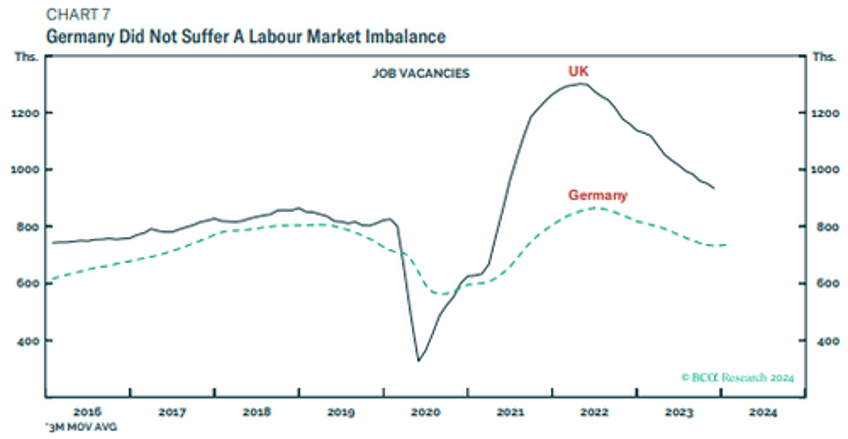

Turning briefly to Europe, the evolution in UK wage inflation is also largely the result of the post-pandemic imbalance between labour demand and the supply of workers, and its subsequent rebalancing.

However, as I explained last week in BCA Research - The UK And Japan Are At Wage Inflation Extremes. Why? the additional shocks of Brexit and the Russia/Ukraine war mean that UK wage inflation, at 6-plus percent, is still far above the 3 percent where it must settle.

As for Germany and the euro area, there has been no significant post-pandemic imbalance between labour demand and the supply of workers. Leaving the ECB with the luxury to cut interest rates before the Fed, and well before the BoE.

Some Investment Conclusions

Structurally, a bullish stance to bonds hinges on central banks not letting inflation stabilise at a level meaningfully above 2 percent and slip-sliding into an era of inflation akin to the 1970s. So far, this bullish structural stance is intact given Powell’s commitment that “we’re not declaring victory at all at this point, we think we have a ways to go.” But any reneging on this commitment would require a rethink.

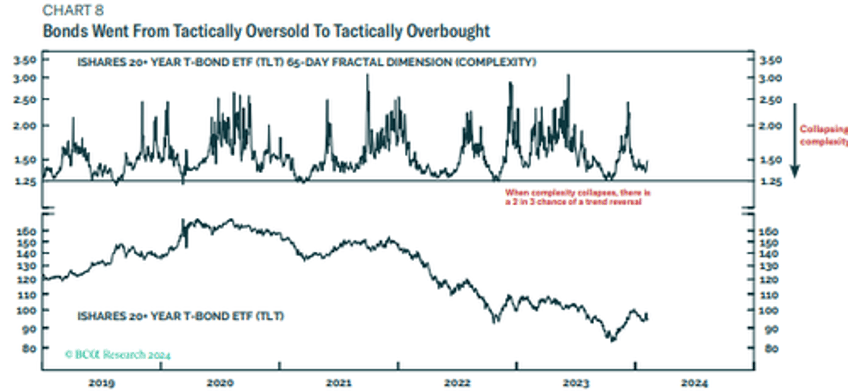

Tactically, our recommendation to buy bonds (TLT) on October 12 and take profits at an 8.5 percent gain proved to be shrewd. The sharpness of the bond rally, premised on the premature popping of champagne corks, went too far too fast – based on its collapsing short-term complexity. This implies a near-term consolidation, warranting a tactically neutral stance to bonds.

Meanwhile, while the S&P500 has grabbed the headlines for reaching an all-time high, the post-October rally is mostly on the coat-tails of the bond rally. So, if bonds consolidate, stocks are likely to consolidate too, also warranting a tactically neutral stance.

Lastly, USD/EUR has upside – because the Fed’s rate cuts will be pushed out further than the ECB’s and/or because any consolidation or sell-off in stocks will favour the haven greenback.