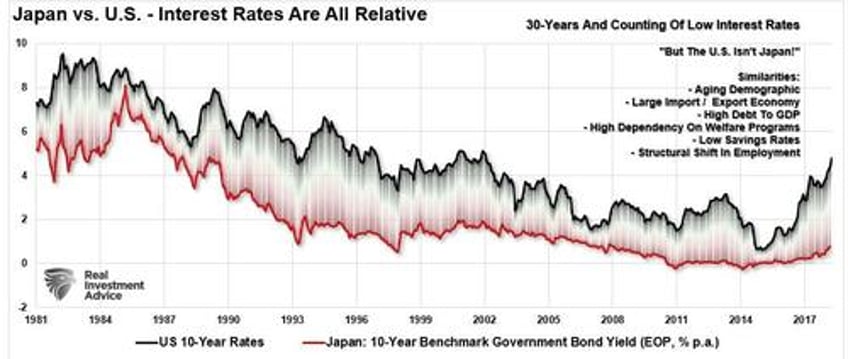

In a recent discussion with Adam Taggart via Thoughtful Money, we quickly touched on the similarities between the U.S. and Japanese monetary policies around the 11-minute mark. However, that discussion warrants a deeper dive. As we will review, Japan has much to tell us about the future of the U.S. economically.

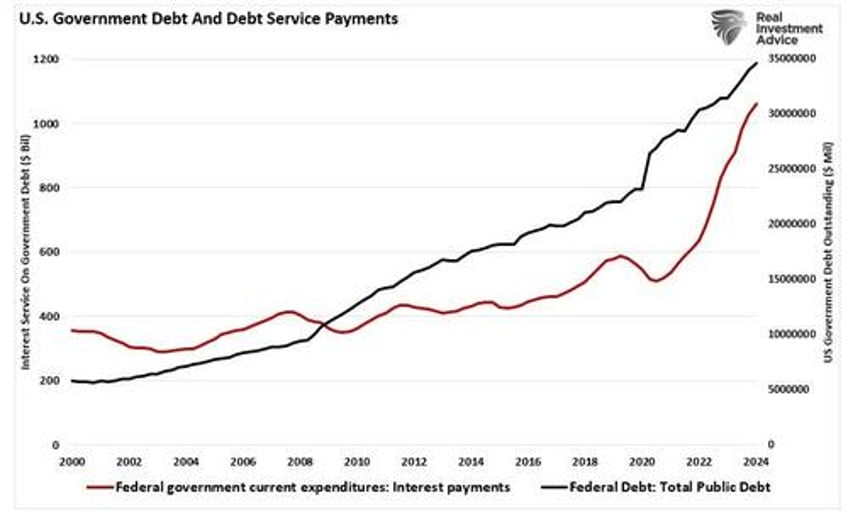

Let’s start with the deficit. Much angst exists over the rise in interest rates. The concern is whether the government can continue to fund itself, given the post-pandemic surge in fiscal deficits. From a purely “personal finance” perspective, the concern is valid. “Living well beyond one’s means” has always been a recipe for financial disaster.

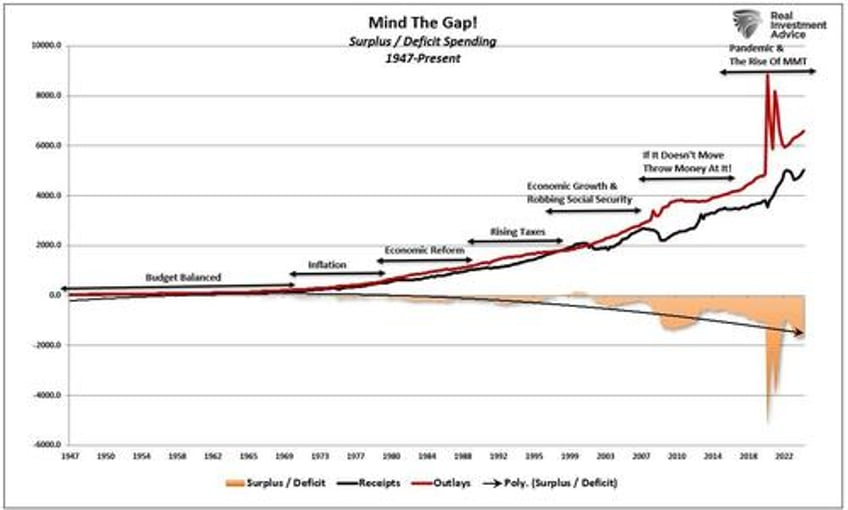

Notably, excess spending is not just a function of recent events but has been 45 years in the making. The government started spending more in the late 1970s than it brought in tax receipts. However, since the economy recovered through “financial deregulation,” economists deemed excess spending beneficial. Unfortunately, each Administration continued to use increasing debt levels to fund every conceivable pet political project. From increased welfare to “pandemic-related” bailouts to climate change agendas, it was all fair game.

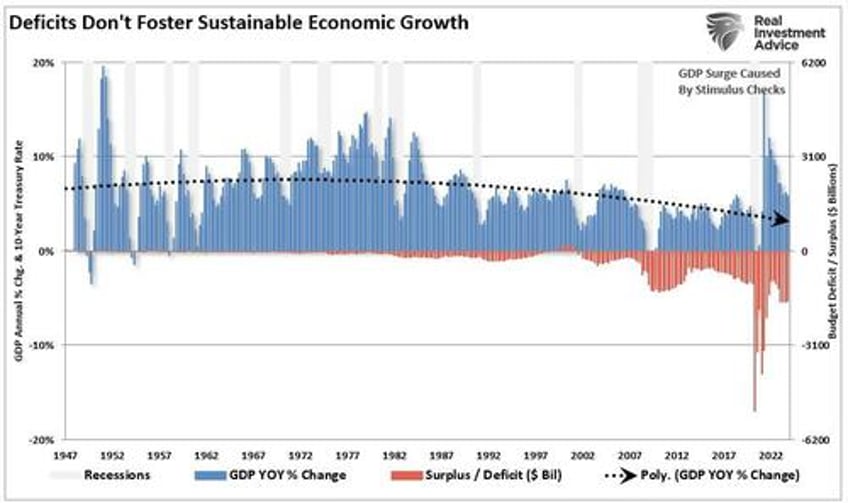

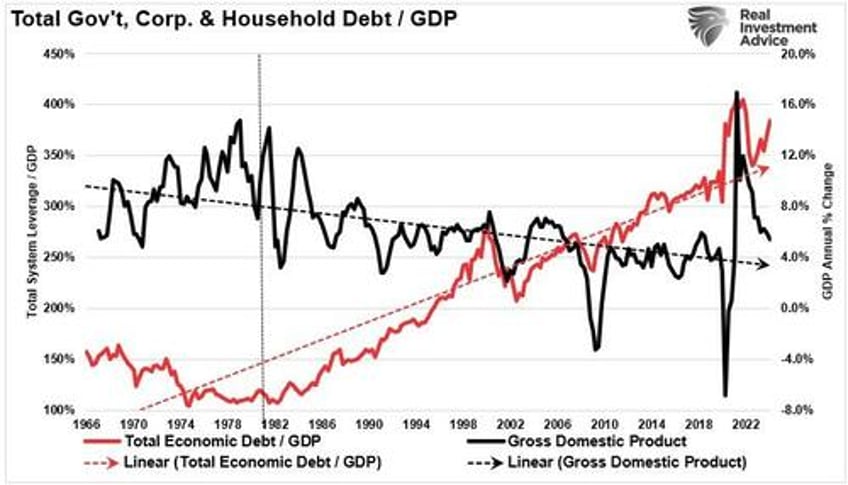

However, while excess spending appeared to provide short-term benefits, primarily the benefit of getting re-elected to office, the impact on economic prosperity has been negative. To economists’ surprise, Increasing debts and deficits have not created more robust economic growth rates.

I am not saying there is no benefit. Yes, “spending like drunken sailors” to create economic growth can work short-term, as we saw post-pandemic. However, once that surge in spending is exhausted, economic growth returns to previous levels. What those programs do is “pull forward” future consumption, leaving a void that detracts from economic growth in the future. That is why economic prosperity continues to decline after decades of deficit spending.

We agree that rising debts and deficits are certainly concerning. However, the argument that the U.S. is about to become bankrupt and fall into economic oblivion is untrue.

For a case study of where the U.S. is headed, a look at Japanese-style monetary policy is beneficial.

The Failure Of Central Banks

“Bad debt is the root of the crisis. Fiscal stimulus may help economies for a couple of years but once the ‘painkilling’ effect wears off, U.S. and European economies will plunge back into crisis. The crisis won’t be over until the nonperforming assets are off the balance sheets of US and European banks.” – Keiichiro Kobayashi, 2010

Kobayashi will ultimately be proved correct. However, even he never envisioned the extent to which Central Banks globally would be willing to go. As my partner, Michael Lebowitz pointed out previously:

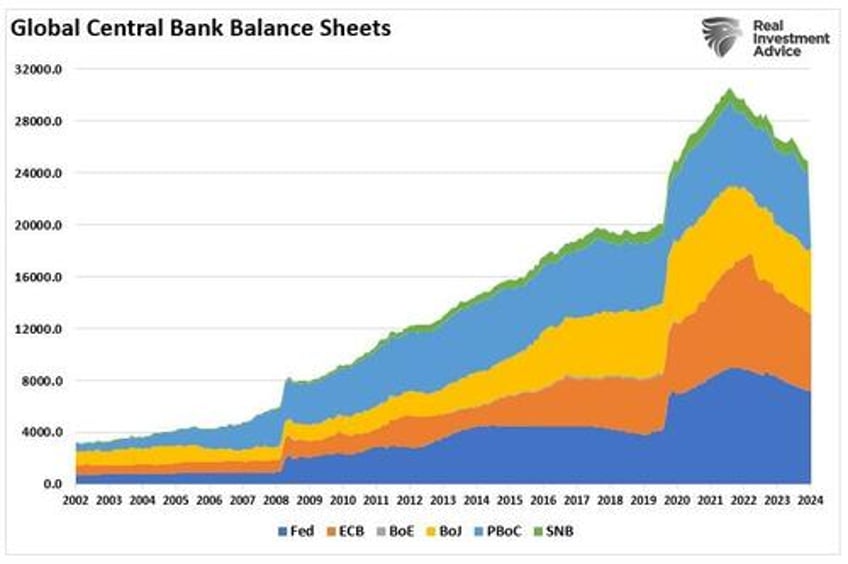

“Global central banks’ post-financial crisis monetary policies have collectively been more aggressive than anything witnessed in modern financial history. Over the last ten years, the six largest central banks have printed unprecedented amounts of money to purchase approximately $24 trillion of financial assets as shown below. Before the financial crisis of 2008, the only central bank printing money of any consequence was the Peoples Bank of China (PBoC).”

The belief was that driving asset prices higher would lead to economic growth. Unfortunately, this has not been the case, as debt has exploded globally, specifically in the U.S.

“QE has forced interest rates downward and lowered interest expenses for all debtors. Simultaneously, it boosted the amount of outstanding debt. The net effect is that the global debt burden has grown on a nominal basis and as a percentage of economic growth since 2008. The debt burden has become even more burdensome.”

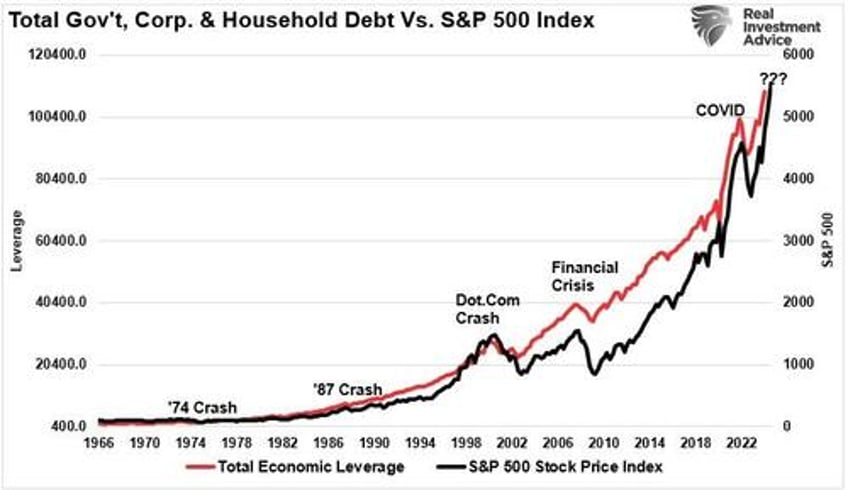

Not surprisingly, the massive surge in debt has led to an explosion in the financial markets as cheap debt and leverage fueled a speculative frenzy in virtually every asset class.

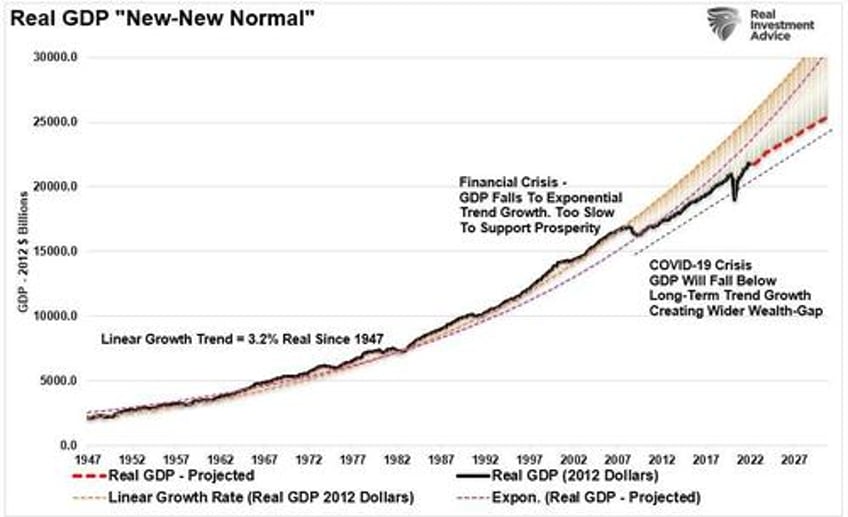

Soaring U.S. debt, rising deficits, and demographics are the culprits behind the economy’s disinflationary push. The complexity of the current environment implies years of sub-par economic growth ahead. The Federal Reserve’s long-term economic projections remain at 2% or less.

The U.S. is not the only country facing such a gloomy public finance outlook. The current economic overlay displays compelling similarities with the Japanese economy.

Many believe that more spending will fix the problem of lackluster wage growth, create more jobs, and boost economic prosperity. However, one should at least question the logic given that more spending, as represented in the debt chart above, had ZERO lasting impact on economic growth. As I have written previously, debt is a retardant to organic economic development as it diverts dollars from productive investment to debt service.

Japanese Policy And Economic Outcomes

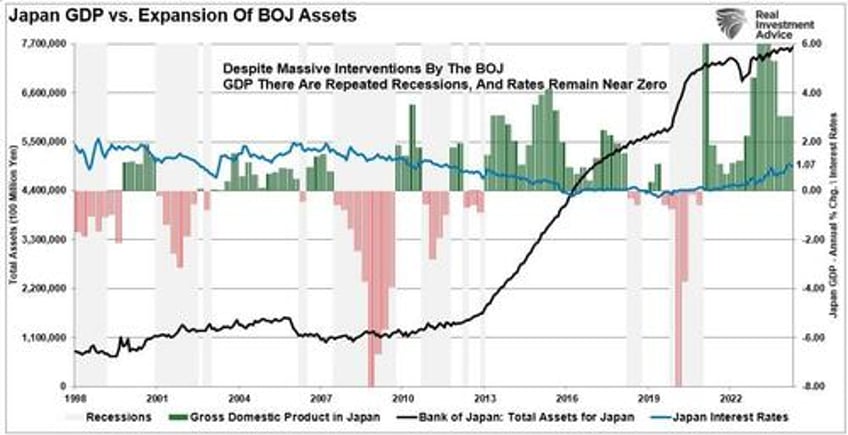

One only needs to look at the Japanese economy to understand that Q.E., low-interest rate policies, and debt expansion have done little economically. The chart below shows the expansion of BOJ assets versus the growth of GDP and interest rate levels.

Notice that since 1998, Japan has been unable to sustain a 2% economic growth rate. While massive bank interventions by the Japanese Central Bank have absorbed most of the ETF and Government Bond market, spurts of economic activity repeatedly fall into recession. Even with interest rates near zero, economic growth remains weak, and attempts to create inflation or increase interest rates have immediate negative impacts. Japan’s 40-year experiment provides little support for the idea that inflating asset prices by buying assets leads to more substantial economic outcomes.

However, the current Administration believes our outcome will be different.

With the current economic recovery already pushing the long end of the economic cycle, the risk is rising that the next economic downturn is closer than not. The danger is that the Federal Reserve is now potentially trapped with an inability to use monetary policy tools to offset the subsequent economic decline when it occurs.

That is the same problem Japan has wrestled with for the last 25 years. While Japan has entered into an unprecedented stimulus program (on a relative basis twice as large as the U.S. on an economy 1/3 the size), there is no guarantee that such a program will result in the desired effect of pulling the Japanese economy out of its 40-year deflationary cycle. The problems that face Japan are similar to what we are currently witnessing in the U.S.:

A decline in savings rates to extremely low levels which depletes productive investments

An aging demographic that is top-heavy and drawing on social benefits at an advancing rate.

A heavily indebted economy with debt/GDP ratios above 100%.

A decline in exports due to a weak global economic environment.

Slowing domestic economic growth rates.

An underemployed younger demographic.

An inelastic supply-demand curve

Weak industrial production

Dependence on productivity increases to offset reduced employment

The lynchpin to Japan and the U.S. remains demographics and interest rates. As the aging population grows and becomes a net drag on “savings,” dependency on the “social welfare net” will continue to expand. The “pension problem” is only the tip of the iceberg.

Conclusion

Like the U.S., Japan is caught in an ongoing “liquidity trap” where maintaining ultra-low interest rates is the key to sustaining an economic pulse. The unintended consequence of such actions, as we are witnessing in the U.S. currently, is the ongoing battle with deflationary pressures. The lower interest rates go, the less economic return that is generated. Contrary to mainstream thought, an ultra-low interest rate environment has a negative impact on making productive investments, and risk begins to outweigh the potential return.

More importantly, while interest rates did rise in the U.S. due to the massive surge in stimulus-induced inflation, rates will return to the long-term downtrend of deflationary pressures. While many expect rates to increase due to the rise in debt and deficits, such is unlikely for two reasons.

Interest rates are relative globally. Rates can’t rise in one country, while most global economies push toward lower rates. As has been the case over the last 30 years, so goes Japan, and the U.S. will follow.

Increases in rates also kill economic growth, dragging rates lower. Like Japan, every time rates begin to rise, the economy rolls into a recession. The U.S. will face the same challenges.

Unfortunately, for the next Administration, attempts to stimulate growth through more spending are unlikely to change the outcome in the U.S. The reason is that monetary interventions and government spending do not create organic, sustainable economic growth. Simply pulling forward future consumption through monetary policy continues to leave an ever-growing void. Eventually, the void will be too great to fill.

But hey, let’s keep doing the same thing over and over again. While it hasn’t worked for anyone yet, we can always hope for a different result.

What’s the worst that could happen?