When it comes to monetary and fiscal policy, Japan is doomed. Unfortunately it is also doomed demographically.

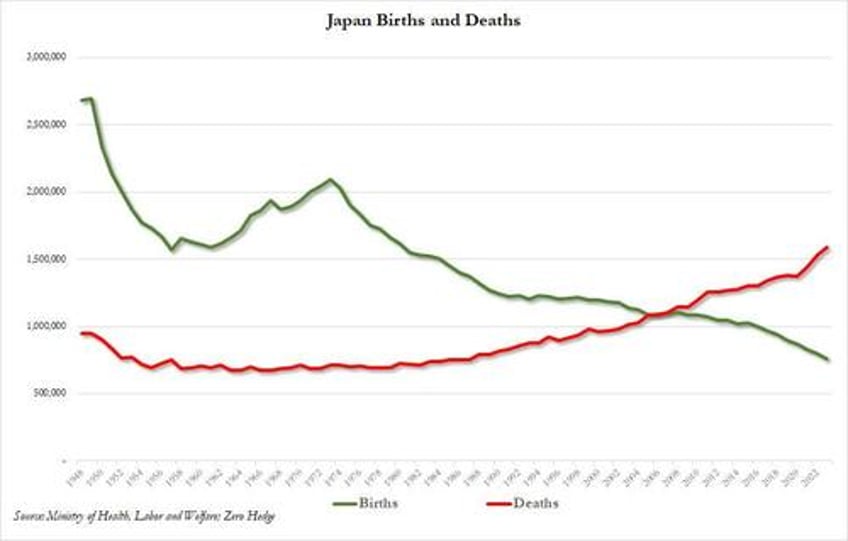

Extending what has long been the most dismal trend in Japan's civilizational history, government data showed that the number of babies born in Japan fell for an eighth straight year to a fresh record low in 2023, underscoring the daunting task the country faces in trying to stem depopulation.

The number of births in 2023 fell 5.1% from a year earlier to 758,631, while the number of marriages slid 5.9% to 489,281, the first time in 90 years the number fell below 500,000 - the last time the number was this low the US had just dropped the atom bomb over Hiroshima and Nagasaki - signaling even greater declines in the population as out-of-wedlock births are rare in Japan.

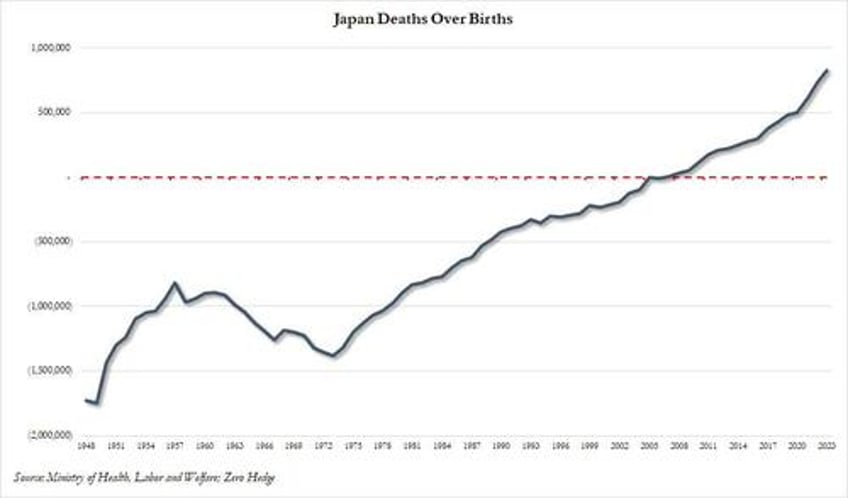

The drop comes more than a decade earlier than the government's National Institute of Population and Social Security Research forecast, which estimated births would decline to below 760,000 in 2035, according to Kyodo news.

Meanwhile, the number of deaths also hit a record - only in the other direction - rising to 1,590,503, while divorces increased to 187,798, up by 4,695.

As a result, Japan's population, including foreign residents, fell by 831,872, with deaths outnumbering births by a record 831,872, double where it was just five years ago.

Asked about the latest data, Japan's top government spokesperson said the government will take "unprecedented steps" to cope with the declining birthrate, such as expanding childcare and promoting wage hikes for younger workers.

None of those measures have led to any perceptive improvement in Japan's demographic bust in the past.

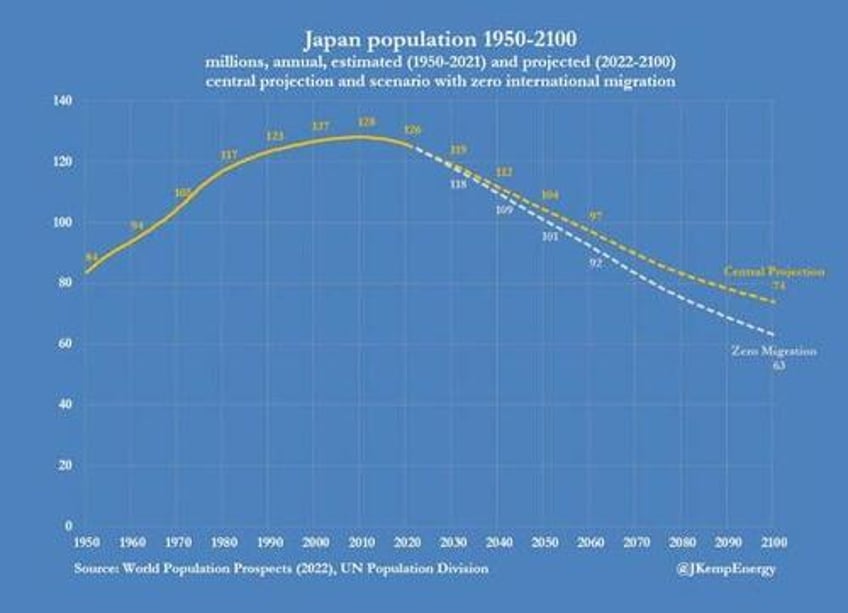

The fast pace of decline in the number of newborns has been attributed to late marriages and people staying single. The administration of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has called the period leading up to 2030 "the last chance" to reverse the trend; all Japan has to do is divert the millions of illegal immigrants entering the US every month through the southern border - with the expectation they will all become diligent Democratic voters - and give them a red carpet welcome.

"The declining birthrate is in a critical situation," Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi told reporters. "The next six years or so until 2030, when the number of young people will rapidly decline, will be the last chance to reverse the trend."

A fall in the number of marriages is clearly followed by a drop in births, said Kanako Amano, a senior researcher at the NLI Research Institute. In order to increase the number of marriages, the government must conduct labor reforms, such as increasing wages in rural areas and eliminating the gender gap, Amano said.

The government is planning on submitting related legislation, including a bill on boosting child allowances to combat the declining birthrate, to the current session of parliament.

The number of births has been on a downward trend after hitting a peak in 1973 at around 2.09 million babies. It fell below 1 million in 2016.

The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare is set to release possibly in June population data excluding foreign residents. The revised figure for 2022 showed births falling to 770,747, down about 30,000 from the preliminary figure. If a similar trend continues in 2023, the number of births excluding foreign residents is likely to total around 730,000.

Mindful of the potential social and economic impact, and the strains on public finances, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has called the trend the "gravest crisis our country faces", and unveiled a range of steps to support child-bearing households late last year.

Japan's population will likely decline by about 30% to 87 million by 2070, with four out of every 10 people aged 65 or older, according to estimates by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.