Back in 1989, Japan was taking over the world. The country’s economy had grown 6.7% in 1988. Sony had just bought Columbia Pictures, one of the largest Hollywood studios, for $3.45 billion. Japanese property company Mitsubishi Estate took control of Rockefeller Center in New York City that October. When land prices peaked in Tokyo, Japan’s Imperial Palace grounds were more valuable than all the land in Florida. – WSJ

At its height, in 1989, real estate in Tokyo sold for as much as $139,000 a square foot—more than 350 times as much as choice property in Manhattan. – Vanity Fair

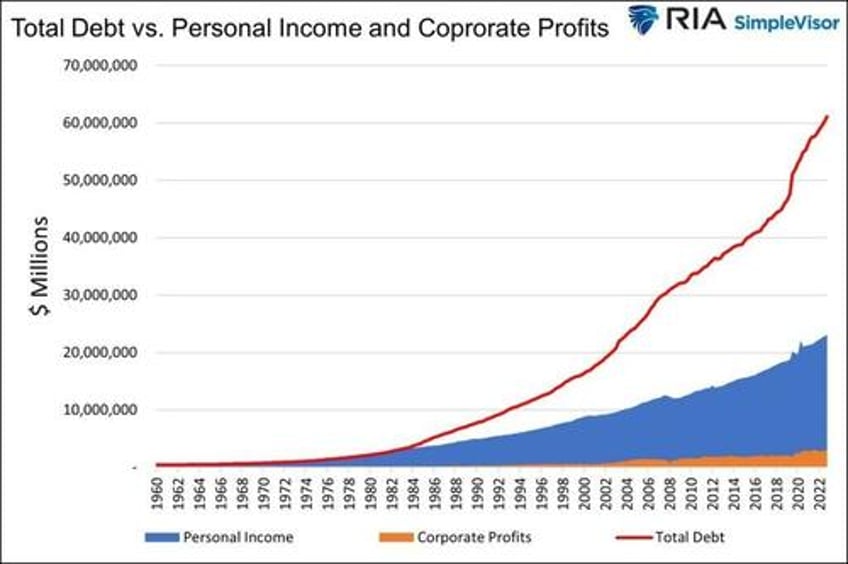

Some say the U.S. economy and financial markets are in epic bubbles. Undoubtedly, our increasing dependence on debt to fund economic expansion and years of prior debt is unsustainable without central bank intervention in markets. Furthermore, there are hints of irrational exuberance in the stock, credit, and crypto markets. While we are in a bubble of sorts, our current situation pales compared to Japan’s bubble and subsequent lost decades.

Japan’s situation then and ours now are in no way an apples-to-apples comparison. However, there are similarities. Accordingly, the lessons Japan learned and the price they continue to pay for extreme leverage and irrational exuberance are worth understanding in hopes we can take steps today and avoid Japan’s lost decades.

Japan’s Twin Bubbles

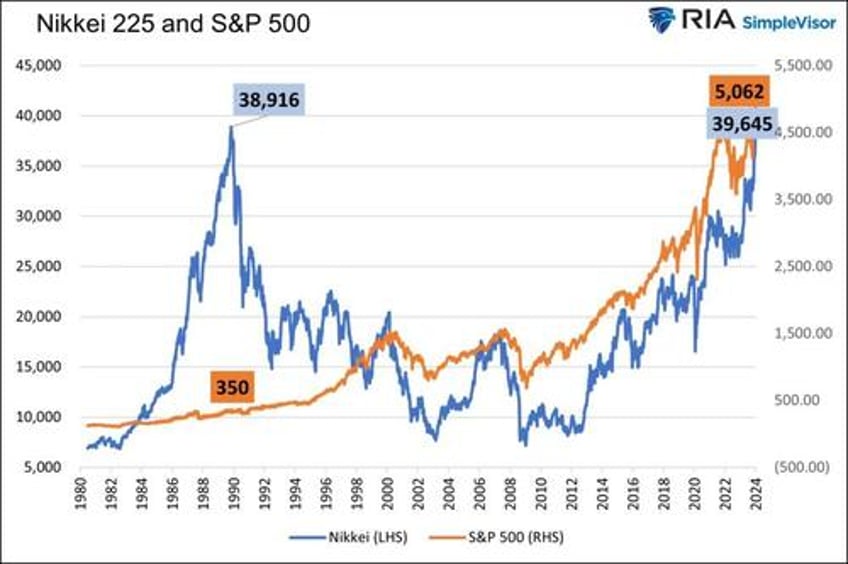

In the first week of January 1990, Japan’s Nikkei 225 stock market index peaked at 38,916. As shown below, the Nikkei index surged 488% in just ten years preceding that record high. At the time, its P/E ratio stood near 60. Today, thirty-five years later, the Nikkei has finally set a new record high. Over the same period (1990 to current), the S&P 500 has risen by 1350%!

It wasn’t just the stock market that was in a bubble in the late 1980s. Real estate values, bolstered by extreme leverage, were skyrocketing. At the time, it was estimated that the total property market in Japan was worth four times the United States’ property value. That is unbelievable, considering the U.S. has about 26 times more acreage. The real estate valuation stats in the opening quotes further highlight the mind-boggling valuations.

Out Of The Rubble And Into The Bubble

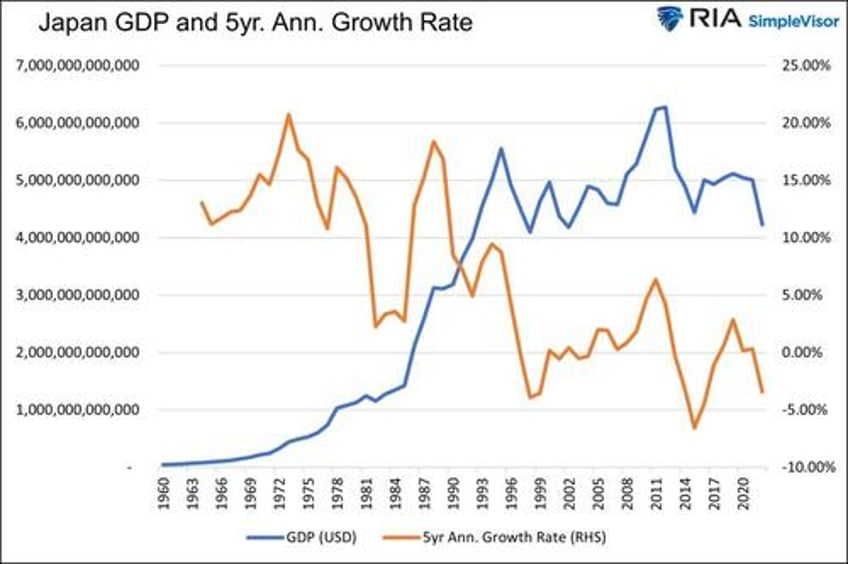

After rebuilding from the devastation of World War II, Japan embarked on an economic boom. It quickly became one of the world’s leading economic and financial powerhouses. In 1970, Japan’s GDP was $217 billion. By 1990, it had grown to $3.19 trillion, an astonishing 14.4% annual growth rate. In context, economists have marveled at China’s single-digit growth rate since 2000.

Their massive economic gains came to a complete halt in the mid-1990s, marking the beginning of “Japan’s Lost Decades.”

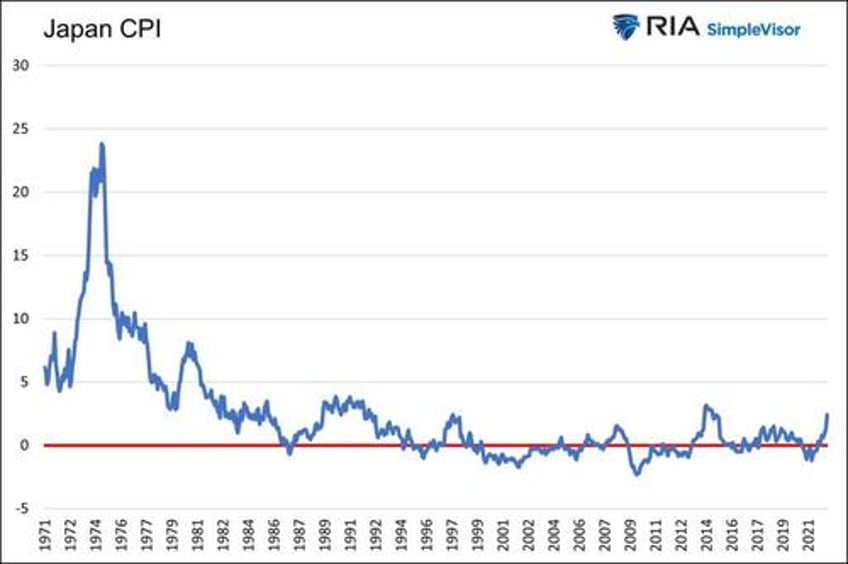

Since then, Japan has been plagued by economic stagnation and deflation. The first graph below shows Japan’s GDP has shrunk since 1995. Similarly, prices have been flat over the same period, with numerous bouts of deflation.

The Long Road To Recovery

There are many factors contributing to Japan’s lost decades.

At the bubble’s apex, in December 1989, the government and Bank of Japan (BOJ) implemented policies to prick its asset bubbles. Hindering the banking system’s ability to create new debt and refinance old debt put a pin in the stock and real estate bubbles. The banking system was in grave danger, with asset values falling precipitously and the loans backing said assets lacking sufficient collateral.

For better or worse, the government supported the banks to prevent catastrophic failures. Japan likely avoided a banking crisis and economic depression on par or possibly worse than our own experience in the 1930s. Unfortunately, the banks became zombies. They could not write off bad loans; thus, their ability to create new loans or refinance maturing loans was severely limited. Japan effectively avoided a massive depression but ended up with decades of economic stagnation. Pick your poison!

Lingering Demographic Effects

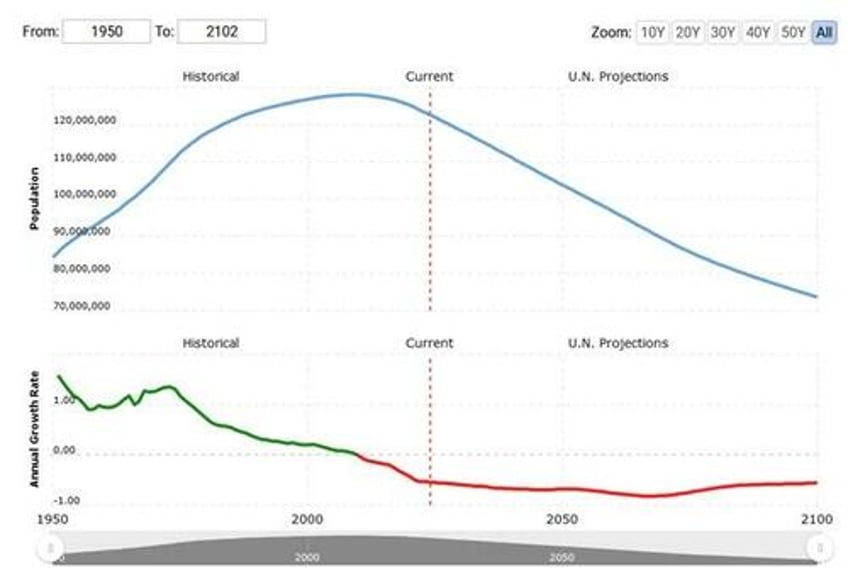

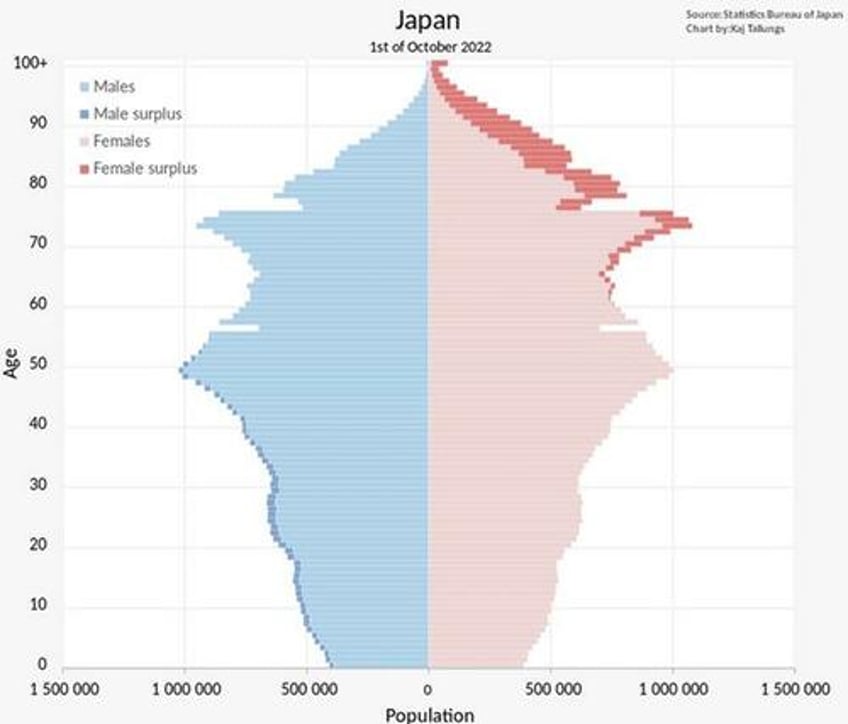

Further accentuating Japan’s lost decades of economic woe is its declining and aging population. The first graph below, courtesy of Macro Trends, shows that Japan’s population growth peaked in 2009 and has declined since. Further concerning, the second graph shows that a large percentage of their population is over 50 and supported by a shrinking base of younger people.

One significant consequence of Japan’s prolonged economic stagnation was its impact on the labor market and demographic landscape. High unemployment rates, particularly among the youth, and stagnant wages became the norm. The result was poor sentiment, which led to declines in personal consumption and confidence. Consequently, the desire to have children declined broadly across their population.

Many adult children continue to live with their parents and refuse to work or get married and start families.

Making demographic matters worse, Japan has strict immigration laws. Its net immigration rate is .74 per 1,000 people compared to 3 per 1,000 for the U.S. Given its low net migration rate, Japan has been unable to offset its negative birth/death rate with foreigners.

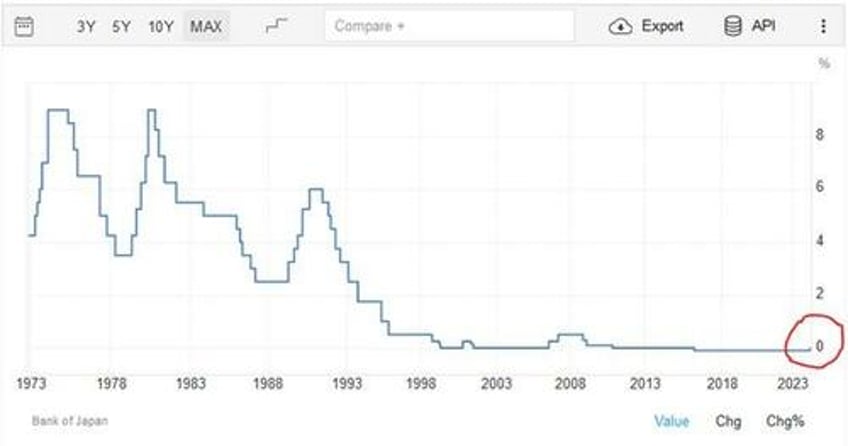

The BOJ

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has done everything it can to support the economy and banks. The graph below from Trading Economics shows that its key lending interest rate has been near zero for over 20 years. They recently raised their lending rate to 0-.10%. If you squint, you might see the rate increase highlighted with the red circle.

Furthermore, they have heavily relied on asset purchases (QE). The World Bank estimates that the BOJ’s assets are a stunning 89% of Japan’s GDP. That is nearly triple that of the Fed. Furthermore, the BOJ owns approximately 60% of the stock ETF market and is the top shareholder of over one-fifth of the Nikkei 225 companies. They also hold over half of the nation’s Treasury securities.

They claim they are trying to normalize policy. However, with the yen trading at 20-year lows and depreciating versus the dollar, the BOJ will have to prove its claim via higher rates and less QE. Is Japan’s banking system and economy able to handle such a normalization?

Summary

Japan made critical mistakes in the 1970s, fostering one of the largest financial bubbles in history. It can also be criticized for its handling of the bubbles’ fallout.

Their struggle to regain economic and monetary policy normalcy highlights how the bubble still dramatically impacts the nation.

It’s not too late for America to manage her finances better. Unfortunately, most politicians want to get re-elected and will not do what is best for America. Continuing down our path will eventually lead to Japan circa 1989. But do not mistake our situation with that of Japan forty years ago.