While La Ñina is helping ease the traffic knots at the Panama Canal, repeated attacks by Houthis — some fatal — have driven shippers to find alternatives to the Suez Canal, said Ryan Loy, extension economist for the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture.

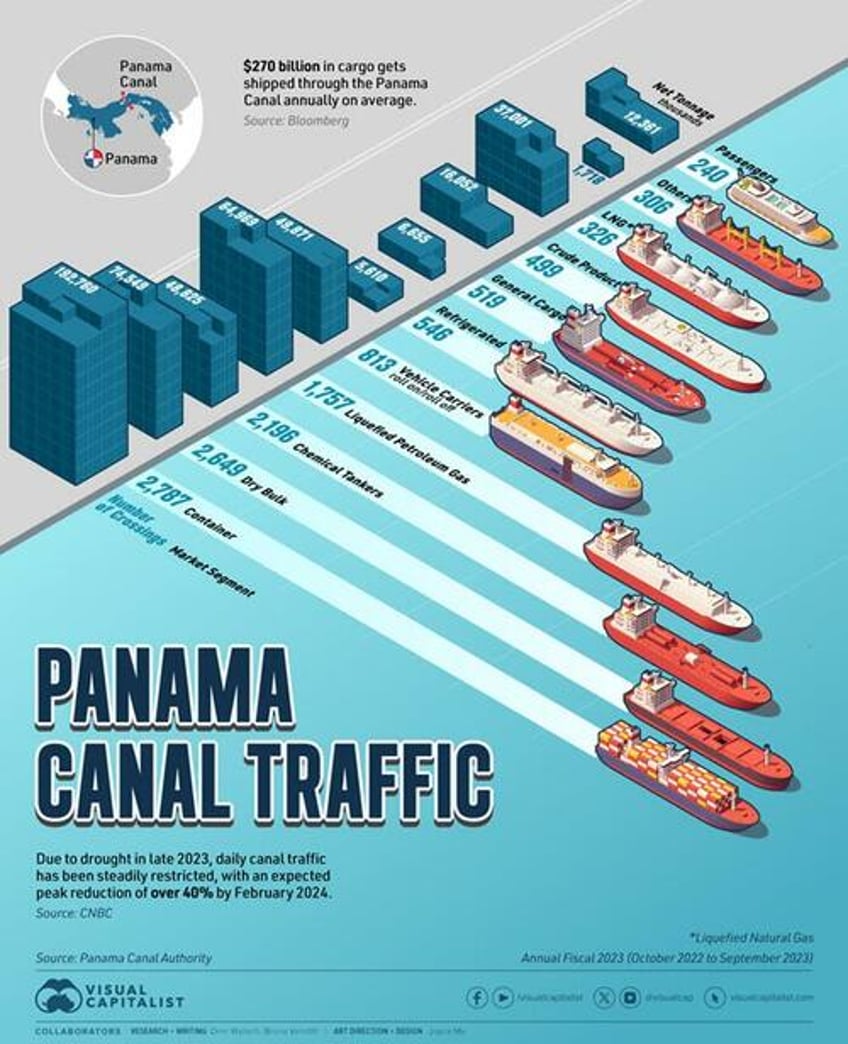

The Panama Canal is a key route for global trade, including for Arkansas commodities such as soybeans and corn. In March, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development said that traffic through the Panama Canal had dropped 49 percent since 2021 and 42 percent in the Suez Canal during the same period.

“About 26 percent of U.S. soybeans and 17 percent of U.S. corn is transported via the Panama Canal,” Loy said. “And this is important to us, especially in Arkansas, because a lot of our grain goes down the Mississippi River to the Port of New Orleans.”

Arkansas’s export soybeans and corn go through the Panama Canal to get to Asia, Loy noted.

Long-term drought across Central America was strangling the Panama Canal. While the passage connects two oceans, the water used to raise and lower ships between the coasts comes from Gatun Lake, a fresh water body. Each ship transit requires 52 million gallons of water. The lake fell to its lowest levels in five years last June, hitting 79.5 feet.

“It was a very dire situation,” Loy said. The alternative to the canal would mean sailing around Cape Horn at the bottom of South America, costly in fuel and fraught with dangerous weather.

Lower lake levels meant shallower water in the locks. The Panama Canal Authority ended up restricting the number of ships making transits. Ships that could make the trip had to carry less cargo to prevent their hulls from hitting bottom.

However, the return of La Ñina has meant replenishing rain for the lake and the canal authority has not only increased the number of ships allowed through, but also allowed heavier ships that sit more deeply in the water.

As of July 11, the canal authority was “increasing the number to 33 ships a day. Then on July 22, they’re going to allow 34 ships a day and on Aug. 5, they will open up one more spot for the Neopanamax ships.”

“Neopanamax” refers to the largest ships than can pass through the canal’s newest locks, which opened in 2016. These vessels can be up to 1,202 feet long, 168 feet wide and have a draft of 50 feet. Draft is the distance between the ship’s waterline and its lowest point.

“This is very close to what they used to do — 38 ships a day — so we’re getting close to normal,” Loy said. “Just for comparison, in November 2023, they were at 24 ships a day, so you can see how much we’ve kind of improved since then.”

Should drought return the canal to its restricted state and if China’s soybean crop is poor, “that leaves Brazil an opportunity,” he said.

Brazil is a key rival to the U.S. for soybean trade and doesn’t rely on the Panama Canal.

“Brazil can come in and say, we don’t need the Panama Canal. We can transport our grain via rail and trucks to the Pacific. They have a lot of it and it’s much cheaper,” Loy said. “So those are the kind of implications of what could happen if the drought comes back.”

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is a critical route, carrying an estimated 12-15 percent of global trade.

Since starting in November 2023, Houthi attacks in the Suez Canal have become fiercer, resulting in the deaths of four crewmembers from attacks on two ships, the MV True Confidence and the Tutor.

MarineTraffic.com, which tracks global shipping, reported a 79.6 percent reduction in dry bulk carriers — whose shipments include grain — passing through the Suez, just 24 ships in June, compared to 118 in June 2023. The amount of cargo passing through the canal in May was 44.9 million tons, down from 142.9 million tons in May 2023.

The U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency said many shippers were opting to avoid the canal and the Houthis, including British Petroleum, Evergreen, CMA CGM, Hapag Loyd and Maersk.

Maersk resumed its use of the canal in June, since taking the the Cape of Good Hope route around the tip of South Africa added an estimated $1 million in fuel costs and one to two weeks in additional transit time, according to the U.S. Naval Institute. Rounding the cape is still perilous, with one ship running aground and another losing cargo, according to Bloomberg.

The Suez Canal’s decreased traffic meant the port authority’s yearly revenues were nearly halved, from $648 million last year to $337 million, Loy said.

“The areas surrounding this are also impacted, too, because people’s jobs, people’s livelihoods depend on traffic through the Suez Canal,” he said, and “that’s tough for that region.”

Houthis are only attacking ships affiliated with the U.S., Israel and their allies, affecting insurance premiums for the carriers.

“The total premium for U.S.-based cargo is 1.7 percent of total freight on board,” Loy said. “Because they’re not attacking Chinese ships, the Chinese premium is just 0.2 percent of the value of total freight on board.”

Where does this leave consumers?

“I’m surprised that we haven’t seen much increase in items at the grocery store, even vehicles, or whatever it may be, anything besides grain, that are separate from our inflation issues,” Loy said. “The expected big ripple effect is having a little bit less of an impact than most people thought.”