By Peter Tchir of Academy Securities

Rates, “Credit”, and Geopolitical Inflation

Rates dominated the market this week. Equities seemed to follow rates around, but that correlation broke down on Friday afternoon as yields moved lower (and stocks slumped). We will address rates and the “credit” story (which is really about the credit of the U.S. government). We will also re-emphasize several sources of inflation that seemed to garner attention this week.

Rates

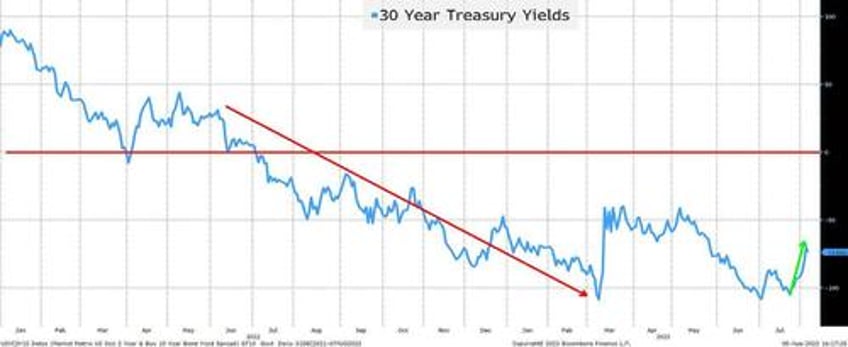

The 30-Year Yield Breaks Above 4%

For the second time since the Fed started hiking, the 30-year materially breached the 4% level. It had done that back in October 2022. At that time, the S&P 500 was at 3,600, a long way from today’s lofty level of 4,500. That move in Treasuries back in the autumn of 2022 was quickly followed by a move taking the 30-year Treasury back to 3.5%. It is unclear if that can or will happen again. It is also unclear if equities can be valued so highly now compared to then.

There are a few things that are “different” this time (yes, famous last words), but let’s first look at the other move in rates that caught my eye (and one that I’m completely on board with).

2-Year Yield vs 10-Year Yield Much Less Inverted

There are a few key differences in today’s environment compared to late 2022.

- Landing. A soft landing seemed like wishful thinking back then, and while I’m dubious that it will happen, it is impossible not to admit the real possibility that we’ve made it through the worst of the Fed and survived. Clearly this possibility is one of the biggest drivers and helps explain why (unlike in late 2022) the curves are becoming less inverted as yields rally.

- Fed.

- The Fed was looking for excuses to hike (and any excuse that they could find turned into hawkish rhetoric and a hike). We are in an environment where the Fed is increasingly reluctant to hike and seems willing to play the “long and variable lag” card if they need an excuse to pause or skip a meeting.

- The markets were willing to ignore the Fed’s insistence that they wouldn’t be cutting any time soon, but now they have been beaten into submission. The Fed has been effective at convincing markets that rate cuts are unlikely.

- While the Fed was comfortable creating a recession this year, my belief is that the Fed is less willing to force us into a recession in an election year. The Fed is apolitical, so I’m not sure how valid my belief is, but I’d argue that creating a recession in an election year would influence the elections (it tends not to be good for incumbents). This means that forcing a recession could be viewed as being political, so they’d want to avoid it. Yes, all a bit weird, but the lessons of President George H. W. Bush, who went from being wildly popular to losing his bid for a second term (at least in part due to a recession that occurred while he was in office) cannot be lost on the Fed and certainly not on the politicians who seem more and more comfortable trying to exert influence on the Fed via the media.

- Inflation. Double digit inflation is scary! Heck, even 5% inflation is scary and makes for great headlines. I’m not sure that 4% or even 3% strikes fear into the hearts of the American consumer or into the hearts of politicians craving soundbites to push the electorate one way or the other. While there is a lot of talk about sticky inflation (and some of the longer-term inflation risks that we’ve been discussing for ages), it will take a lot to motivate the Fed, the politicians, and the media. •

- Term Premium. There is a lot of chatter about term premium. This makes sense to me. The Fed is unlikely to cut. Given some longer-term inflation pressures, it is easy to see the Fed move its “terminal” rate higher. So, if the “terminal rate” (lower than today’s rate) moves up over time, that will support higher yields at the longer end. The longer it takes for the Fed to cut rates to the terminal rate, the more support there is to keep longer-term yields higher. But is that enough to take us above last year’s high yields? I suspect not.

- Debt Issuance. The growth in U.S. debt and the need to issue more bonds across the curve will put pressure on yields to go higher as a simple matter of supply and demand. But it also leads to some other questions.

"Credit"

Fitch downgraded the U.S. debt rating to AA+. At the time, I took the stance that “investors don’t buy Treasuries based on ratings”. That quotation was picked up by a myriad of financial publications (including Bloomberg, The New York Times, and the Financial Times). I completely stand behind that quotation and think that the downgrade was relatively trivial in the grand scheme of things.

I got some pushback, and maybe that is why stocks did poorly. The argument goes that if you make the “least risky asset” slightly riskier, than more risk premium must get priced into everything (from the long-end of the yield curve, to credit spreads, and also into equity valuations). I could have always “bought into” (or in this case “sold into”) the argument if something had really changed. But the difference between AA+ and AAA seems trivial to me. Sure, BB and AA are different, but what the heck is the difference between AAA and AA+? I’ve got more important things to worry about.

In an era where the NRSROs (Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations) have been looking to reduce the amount of debt that gets rated AAA, it isn’t at all surprising that the entities would take an opportunity to nudge ratings down slightly. If anything, the surprise to me is how long it took for another company to follow S&P’s lead.

I have no issue with the downgrade.

- We are growing debt at a rapid pace in bad times and good. Somehow, we seemed to have gone from a nation that went into deficit spending in times of trouble (but made efforts to rein it in during good economic times) to increasing debt during what looks like economic “boom” times. Once upon a time, we seemed to experience debt “hangovers” (where we woke up one morning and promised ourselves that we wouldn’t do that again). Now we are a nation that wholeheartedly embraces the “hair of the dog” concept. This seems to be a shift in our attitude towards debt and would make me nervous about rating our debt as AAA.

- Barely a pretense of worrying about debt and deficits. I read somewhere that the last time Congress completed all appropriation bills on time was over 20 years ago (in 1996). I’m not an expert, but that doesn’t seem good. The “debt ceiling” (which we will come to in a moment) is clearly not a “ceiling” in any way that you or I understand a ceiling. The party not in charge sometimes seems to hint about being concerned about debt, but the reality seems to be that they just don’t like that the debt is increasing on expenditures (other than the expenditures they want). When I think of D.C. right now, I think of “bread and circuses”. This was the Roman technique of keeping people happy by spending money that they didn’t have. This changing attitude seems to be worth something when considering the creditworthiness of the nation.

- Threatening not to pay on time. It seems ridiculous that periodically we get confronted with the so-called debt ceiling and that more and more we seem willing to test it out and see if they can push us into non-payment (even for a few days). It seems like this should be a non-starter, but we flirt with it periodically, and while it hasn’t gone past the flirtation stage, it is possible that we could move beyond it. This is another reason to think that AAA might be a bit too good.

- I do not understand why:

- Policies can be passed that will inevitably lead to breaching the debt ceiling. Why, if something would likely push us over the debt ceiling, is it allowed? Not passing policies that are guaranteed to breach the debt ceiling would be a more interesting (and possibly effective) approach to managing the debt ceiling.

- Why don’t we examine government policies and their impact on the budget for 10 years? Computers aren’t powerful enough to go beyond that? Since the debt ceiling isn’t really a debt ceiling, I guess that it doesn’t matter how far out we run our projections, but it seems weird to me that 10 years seems to be the limit of what is projected, which in turn, influences policy decisions.

I guess that is a long way of saying that I think the message being sent to D.C. by Fitch is that “we are heading in the wrong direction and while it isn’t remotely concerning from a risk standpoint today, we can’t just let you go down this path without at least raising our hand and trying to get your attention.”

Geopolitical Inflation

Our position on longer-term inflation is:

- Inflation will run 3% to 5% on average for 3 to 5 years.

That has been our position for some time now and is largely (but not totally) driven by the efforts that the country and companies are taking to make their supply chains “more secure”.

We first tried to hammer home the point that ESG is Inflationary in March of 2021. I view “ESG Inflation” as a subset of “Geopolitical Inflation”. The two main themes of “ESG Inflation” were:

- If it was the cheapest way to produce goods, then we’d already be doing it.

- Certain places produce goods more cheaply for the “wrong” reasons.

We had some conditions that would be required for “ESG Inflation” to gain momentum:

- Consumers willing to pay more for ESG friendly products.

- Investors willing to pay more for ESG friendly companies.

I think that we could substitute “ESG” with “Security” or “Geopolitical” and come to the same conclusions, which are:

- 1. Companies and countries are thinking about supply chains from more than just a simple “cost” analysis (and that is inflationary).

- 2. The conditions for companies to act exist (not having access to your products will do that to you).

This fits in perfectly well with our Battle for Rare Earths and Critical Minerals theme. Global Relations Cooling is another key element of all of this “Geopolitical Inflation”. We hit on many of these inflationary and problematic issues at our Geopolitical Summit West earlier this year.

I cannot believe The Recentralization of China is 2 years old or that World War v3.1 may be far more broadly applicable than originally thought.

The flipside of the coin is the potential risk to sales for U.S. corporations if we are correct in the Shift From Made in China to Made By China and their increasingly deft use of their currency to shift power away from the West. Potential lost sales by non-Chinese companies (especially into emerging markets) would hurt earnings power. It isn’t part of the “inflation” argument, but it is a real risk that should be aggressively addressed now before it is too late and we find ourselves well down a slippery slope.

I could, quite easily, link to even more reports, but I’m running out of time, and you get the gist – this is a subject that is near and dear to my heart and one I think that we all need to be thinking about.

In any case, I expect inflation to be persistently higher for longer than it has been in the past few decades as every step of creating “secure” supply chains will increase costs (at least until they have been rebuilt). The term “secure” can also apply quite broadly.

My 3% to 5% estimate for 3 to 5 years is admittedly a finger in the air estimate and maybe I’m too low (or too short), but that is my working premise on inflation.

Is the 80 Cent Widget More Expensive than the 1 Dollar Widget?

This is the analogy that we use in meetings. It is meant to provoke thought and discussion and I think that this is relevant to most companies.

A few years ago, if it cost 80 cents to make a widget (say in China), but $1 to make the widget in the U.S., the choice was obvious – China.

But now companies are examining the accuracy of that 80 cent cost. What isn’t being priced into the 80 cents? Shipping costs? Shipping availability? Pollution? Hazardous or unsavory work conditions? Ability to refuse to produce or ship? How much is the intellectual property theft costing (extra important if I’m correct in the shift to China selling “their” goods and brands globally)? Sure, some things can be insured (driving up the cost), but some of the costs are intangible. Things that we either ignored or dismissed as “unlikely” turned out to have real costs. Are they outliers, or could they be repeated? Maybe another pandemic is unlikely, but our relationship with China seems to be shifting and it is impossible to ignore their growing influence across the globe. So maybe that 80 cent widget really should be viewed as costing 90 cents. Difficult to account for, but maybe an accurate reflection of the true cost.

With a bit of government support maybe we can get that cost down to 95 cents domestically. Bills like the Chips Act are meant to address this.

Finally, if investors value companies which have taken steps to secure/make their supply chains more sustainable and customers are willing to spend a fraction more for such products, then maybe the stock price can go up, even while paying 95 cents instead of 80 cents.

A theoretical and simple analogy, but I think that this is what companies (and countries) are facing in their decision process.

Bottom Line

Geopolitical (supply chain, ESG, rare earths, or any other name) inflation is real and persistent. The downgrade of the U.S. shouldn’t affect risk premiums (as it was negligible) and it wasn’t a “wrong” step to take.

However, this time is “different” enough that even with all that is going on, I think that curves will continue to become less inverted (though driven more by 2-year yields drifting lower than longer yields heading higher). Maybe the new range is 4% to 4.25% on the long bond, but I struggle to get too bearish on Treasuries even with my geopolitical inflation view.