Political affiliation and wealth, it’s speculated, are making a recession look more likely than it really is by introducing systematic bias into the economic data. But this is a distraction. For the data that matters most in gauging the likelihood of a downturn, any potential bias matters little. A robust recession framework shows that the near-term risk of a slump remains low, but is prone to shifting higher quickly.

There is no such thing as unbiased data. How the data is procured and presented will always introduce user bias, and it’s no different with economic data. My colleague Simon Flint recently wrote that recession risk is being overstated due to data biases, while Cameron Crise has previously touched upon apparent political bias in survey data.

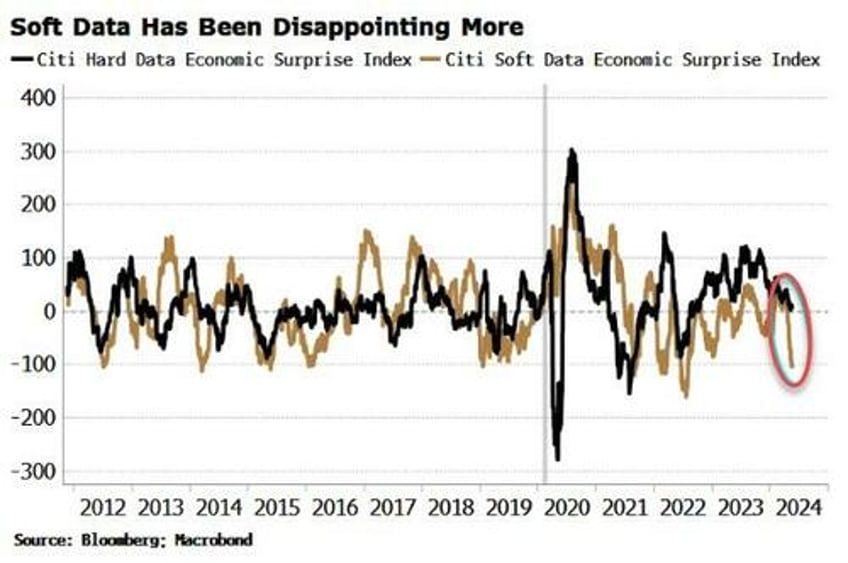

A reader also wrote in with an interesting conjecture that perhaps soft data is more geared to those who are less well off, and hard data the better off.

The recent worse performance of soft data – helping to inch up recession risks – is thus a reflection of worsening wealth inequality rather than a bona fide worsening in economic conditions.

We’ll get to these points, but first let’s answer what should be the prime question for investors, keen to avoid the worst equity-market drawdowns:

Is bias in the data overestimating recession risk?

The short answer is no.

Although there is some bias in economic data, it’s not enough to subvert recession prediction when done robustly. Near-term recession risk today remains low, but that risk could rise rapidly, independent of data bias.

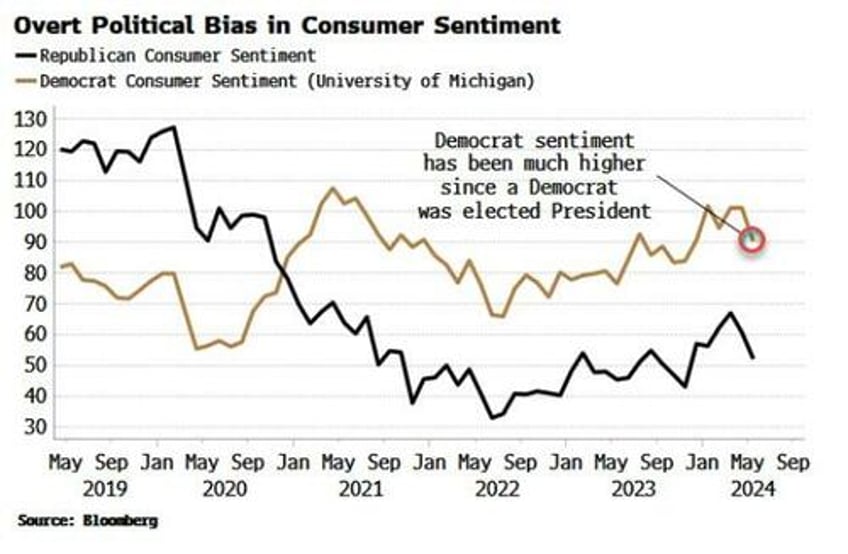

A prevalent bias in some economic data is political. When it comes to some survey data, it can be significant. The Michigan Consumer Sentiment Survey provides a breakdown of political affiliation. Sentiment is being overwhelmingly driven by those who identify as Democrats, and who are currently wildly more optimistic than Republicans.

I am not aware of an explicit breakdown of affiliation in other survey data, but Cameron notes there is an inferable potential skew in the NFIB’s Small Business Optimism Index toward being higher when a Republican is in the White House. Similarly with the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index.

This is all quite interesting, but the core question for investors remains: does it matter for when stock markets experience their worst falls, i.e. recessions?

To begin with, the Conference Board and Michigan’s gauges of consumer sentiment as well as the NFIB are tier-2 data when it comes to predicting downturns.

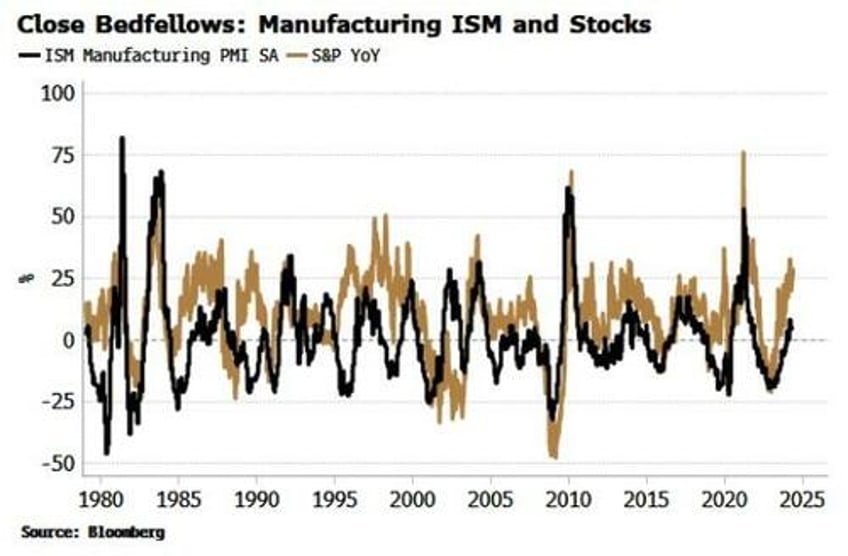

Much better is the manufacturing ISM. As a standalone indicator it excels at unequivocally turning down before a recession begins.

But that’s secondary; the ISM’s real importance stems from it sitting at the nexus between soft and hard data and how they interact to trigger recessions.

This is critical. Recessions metastasize when we get a negative feedback loop developing between hard and soft data. Hard data deteriorates, and this feeds into soft and market data. That in turn hits the wealth effect, which affects investment and spending and feeds back into worsening hard data. Unchecked, a recession typically develops.

The ISM’s role is as a key artery from survey data to the market, and thence ultimately into hard data. The other surveys simply don’t have the same influence, with all of them displaying a much weaker relationship with the S&P.

There is some reflexivity in that ISM-survey respondents’ level of optimism will be affected by the level of the market. But the market also responds to the ISM, as one of the first data points out each month.

Despite Cameron’s view that the ISM does not matter as much as it used to, it in fact remains one of the most important data points (I’ll write more on this very soon).

But we also needn’t overstate its importance. There is no single “killer” recession predictor. The ISM’s utility comes from it having a long history, being minimally revised, having an early release time and its role in facilitating recession-causing negative feedback loops. But other data matter too.

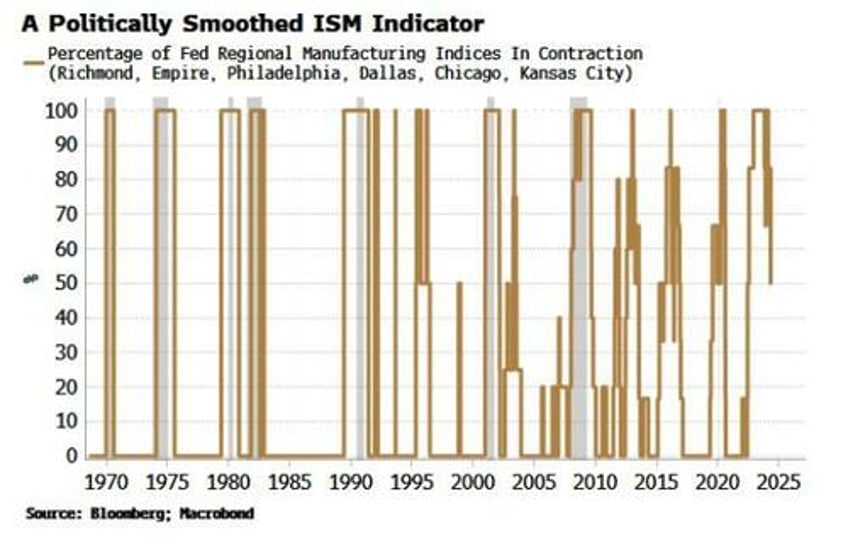

All that said, it would be problematic if the ISM displayed any systematic, significant political bias. There is no data on the political leaning of the survey’s respondents, but we can exploit another feature of recessions to get round any potential bias: their pervasiveness.

Things tend to start going bad everywhere at the same time in a recession. Several Fed member banks produce their own regional manufacturing surveys. The states they cover are fairly evenly balanced overall, with two Democrat strongholds, two Republican ones, and two states that are generally closely fought. This should help even out any potential bias.

A reliable and timely recession indicator, with only a few false positives, has been when all of the regional indexes have been in contraction. Even then this should not be used as a standalone signal. To reiterate, we need to see both hard and soft data self-reinforcedly deteriorating at the same time to trigger a recession.

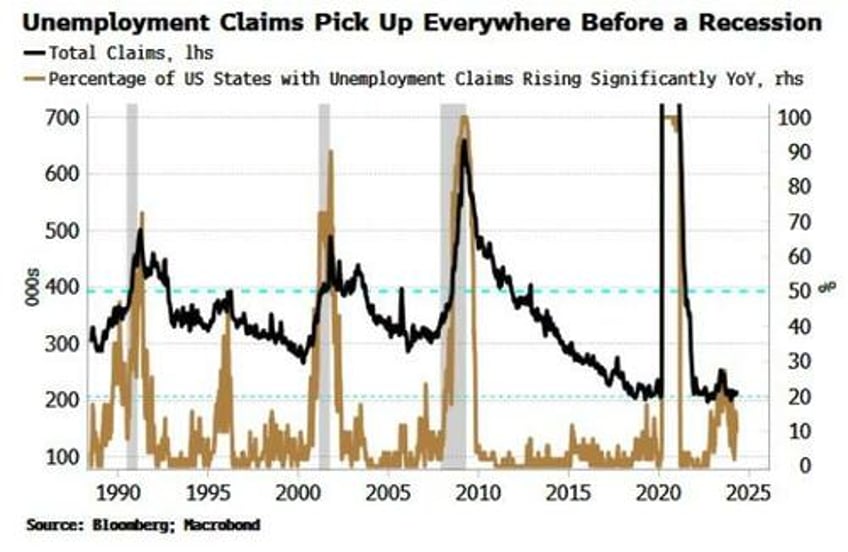

In addition, therefore, we look for a pervasive worsening in hard data too, e.g. the jobs market across states. Unemployment claims in multiple states have picked up sharply ahead of previous recessions.

What about the notion that hard and soft data are biased by wealth inequality, with hard data more geared to the better off, and soft data to the less well off?

Again, there is little bias we can discern. Both better and worse-off households by net worth show a negligible relationship with both hard and survey-based data (even if we use different lags in the data).

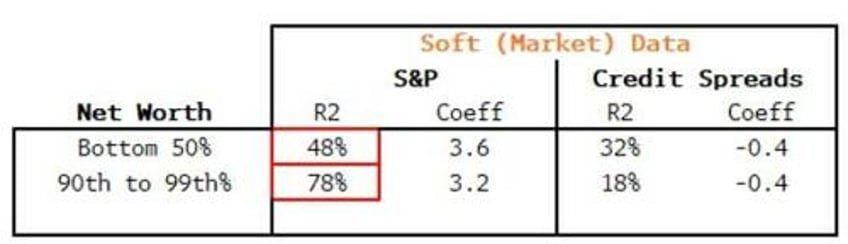

Soft, market-based data does have a much stronger relationship with net worth. But, as the table below shows, stocks have a higher, not lower, R^2 with better-off households than less well-off ones. This is anyway as you would expect given the higher exposure of the wealthier to financial assets.

However, the net worth of less wealthy households has a higher R^2 to credit spreads than better-off ones. That may seem odd at first but is likely explained by credit-spreads’ closer relationship to unemployment.

It’s hard to pinpoint any systematic wealth bias in the data, and likewise it’s hard to find political bias in data that matters for recession prediction, or if so any that we can’t smooth out by exploiting state heterogeneity.

So while it’s recommended to “know your data,” when it comes to what matters - avoiding steep market drawdowns ahead of downturns - investors need not get distracted by second-guessing who votes for whom, and how well-off they might be.