The hypothesis that the Anglo-Saxon axis is pivotal to the proxy war in Ukraine against Russia is only partly true. Germany is actually Ukraine’s second largest arms supplier, after the United States.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz pledged a new arms package worth €700 million, including additional tanks, munitions and Patriot air defense systems at the NATO summit in Vilnius, putting Berlin, as he said, at the very forefront of military support for Ukraine. German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius stressed, “By doing this, we’re making a significant contribution to strengthening Ukraine’s staying power.” However, the pantomime playing out may have multiple motives. Fundamentally, Germany’s motivation is traceable to the crushing defeat by the Red Army and has little to do with Ukraine as such.

The Ukraine crisis has provided the context for accelerating Germany’s militarization. Meanwhile, revanchist feelings are rearing their head and there is a “bipartisan consensus” among Germany’s leading centrist parties — CDU, SPD and Green Party — in this regard.

In an interview last weekend, the CDU’s leading foreign and defense expert Roderich Kiesewetter (an ex-colonel who headed the Association of Reservists of the Bundeswehr from 2011 to 2016) suggested that if conditions warrant in the Ukraine situation, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization should consider cutting off “Kaliningrad from the Russian supply lines. We see how Putin reacts when he is under pressure.”

Berlin is still smarting under the surrender of the ancient Prussian city of Königsberg [now Kaliningrad] in April 1945.

Stalin ordered 1.5 million Soviet troops supported by several thousand tanks and aircraft to attack the crack Nazi Panzer divisions deeply entrenched in Königsberg. The capture of the heavily fortified stronghold of Königsberg by the Soviet army was celebrated in Moscow with an artillery salvo by 324 cannons firing 24 shells each.

Nothing Forgotten in Berlin

Evidently, Kiesewetter’s remarks show that nothing is forgotten or forgiven in Berlin even after eight decades. Thus, Germany is the Biden administration’s closest ally in the war against Russia.

The German government has stated its understanding for the Biden administration’s controversial decision to supply Ukraine with cluster ammunition. The government spokesman commented in Berlin, “We are certain that our US friends did not make their decision lightly, to deliver this sort of munition.”

President Frank-Walter Steinmeier remarked, “In the current situation, one should not obstruct the USA.” Indeed, the top CDU figure, Kiesewetter, suggested in an interview with the Green Party-affiliated daily taz that Ukraine should be given “guarantees, and if necessary, even provided with nuclear assistance, as an intermediary step to NATO membership.”

Coinciding with the NATO summit in Vilnius on Tuesday and Wednesday, Rheinmetall, the great 135-year-old German arms manufacturing company, has disclosed that it is opening an armored vehicle plant in western Ukraine at an undisclosed location in the next 12 weeks.

To begin with, German Fuchs armored personnel carriers will be built and repaired while there are plans afoot to manufacture ammunition and possibly even air defense systems and tanks.

Rheinmetall’s CEO told CNN on Monday that like other Ukrainian arms factories, the new plant could be protected from Russian air attack. Germany has more than doubled the 2022 allocation of €2 billion for upgrading Ukraine’s armed forces. It now touches around €5.4 billion with further plans to increase to €10.5 billion.

Contending with Poland

Now, is this all about Russia? Germany cannot be unaware that Ukraine has simply no hope on earth to defeat Russia militarily. Germany is playing the long game. It is creating equity in western Ukraine where it is not Russia but Poland that is its contender.

Ever since the Tsarist army advanced into Galicia in 1914, Russia has had a difficult history with Ukrainian nationalists. If the current war in Ukraine spreads to western Ukraine, that cannot be Russia’s choice but out of some necessity forced upon it.

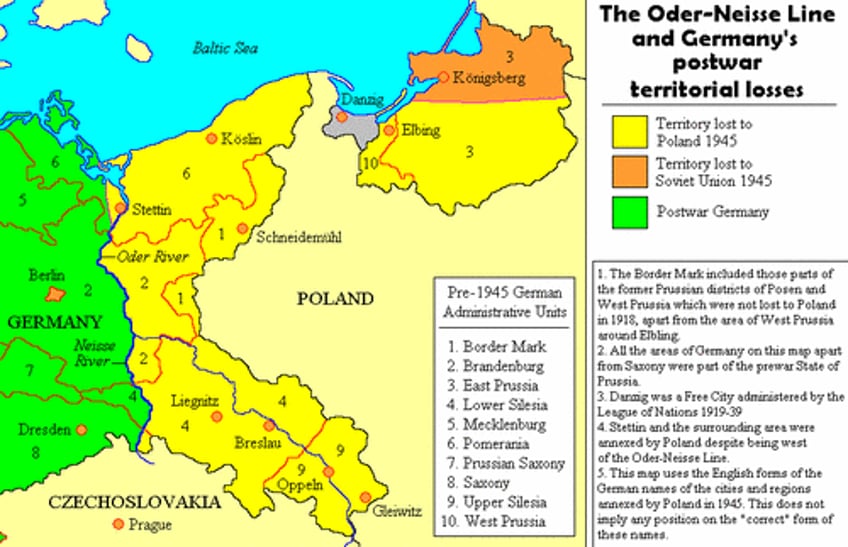

The Soviet victory in Ukraine in October 1944, the Red Army’s occupation of Eastern Europe and Allied diplomacy resulted in a redrawing of Poland’s western frontiers with Germany and Ukraine’s with Poland.

Simply put, with compensation of German territories in the west, Poland agreed to the cession of Volhynia and Galicia in western Ukraine; a mutual population exchange created for the first time in centuries a clear ethnic, as well as political, Polish-Ukrainian border.

It is entirely conceivable that the ongoing Ukraine war will radically change the territorial boundaries of Ukraine in the east and south. Possibly, it can re-open the post-World War II settlement with regard to western Ukraine as well.

Russia has repeatedly warned that Poland aims to reverse the cession of Volhynia and Galicia in western Ukraine. Such a turn of events will most certainly bring to the fore the issue of the German territories that are part of Poland today.

Perhaps, it was in anticipation of turbulence ahead that last October, eight months after the Russian intervention began in February 2022, that Warsaw demanded WWII reparations from Berlin — an issue which Germany says was settled in 1990 — to the tune of €1.3 trillion.

Under the Potsdam Conference of 1945, the “former eastern territories of Germany” comprising nearly one quarter (23.8 percent) of the Weimar Republic with the majority was ceded to Poland. The remainder, consisting of northern East Prussia including the German city of Königsberg (renamed Kaliningrad), was allocated to the Soviet Union.

Make no mistake about the importance of the eastern border for German culture and politics. Indeed, there is always something volatile about a “handicapped” Great Power when a whole new intensity appears in political, economic and historical circumstances, which prompts those in power to turn ideas into reality, and revanchist and imperialistic discourses that were quietly but steadily streaming below the surface of the carefully considered diplomatic efforts begin to probe pan-nationalist expansion.

In retrospect, Germany’s — in particular, then foreign minister and current President Steinmeier’s — diabolical role to align Germany with the neo-Nazi elements during the regime change in Kiev in 2014 and the subsequent German perfidy in the implementation of the Minsk Agreement (“Steinmeier formula”), as admitted as recently in February by former Chancellor Angela Merkel should not be forgotten.

Suffice it to say, even as Russia is winning the Ukraine war, the concern of the German foreign policy makers once again faces the need to redefine what was German.

Thus, the war in Ukraine is only the means to an end. Recent reports suggest that Berlin may be moving, finally, toward meeting Ukraine’s pending demand for Taurus cruise missiles with a range exceeding 500 kms and unique “multi-effect war head” that can be a game changer in the combat dynamics on the battlefield and create the prerequisites for victory.

Equally, German soldiers already comprise about half of the NATO battlegroup already present in Lithuania. Defense Minister Boris Pistorius said two weeks ago while on a visit to Vilnius that Germany is preparing the infrastructure to permanently base 4,000 soldiers (“a robust brigade”) to Lithuania so as to have the capability to maintain military flexibility at the eastern flank. The decision has support from both Germany’s governing coalition and its main opposition.

The CDU foreign policy expert and member of the Bundestag, Kiesewetter called the idea of establishing a German base in the Baltics a “decision of reason and reliability.”

Indeed, there have been past attempts, historically speaking, to create German rule in the Baltics based on revisionist claims towards the new states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania where German colonists had settled as far back as in the 12th and 13th centuries.

M.K. Bhadrakumar is a former diplomat. He was India’s ambassador to Uzbekistan and Turkey. Views are personal.