By Stefan Koopman, Senior Macro strategist at Rabobank

Things Can Only Get Better

Let’s go back to Wednesday afternoon. In a moment of political irony, UK Prime Minister Sunak stepped out of his office to announce an election, hoping for a reset after a series of failed attempts, only to be met with a downpour that seemed to mock his unshielded stance. As he spoke of trust and strategy, the rain drenched him, visually contradicting the message he tried to convey. The situation even turned tragicomical when music from a campaigner’s sound system interrupted him, playing “Things Can Only Get Better” and adding a soundtrack to the faltering speech.

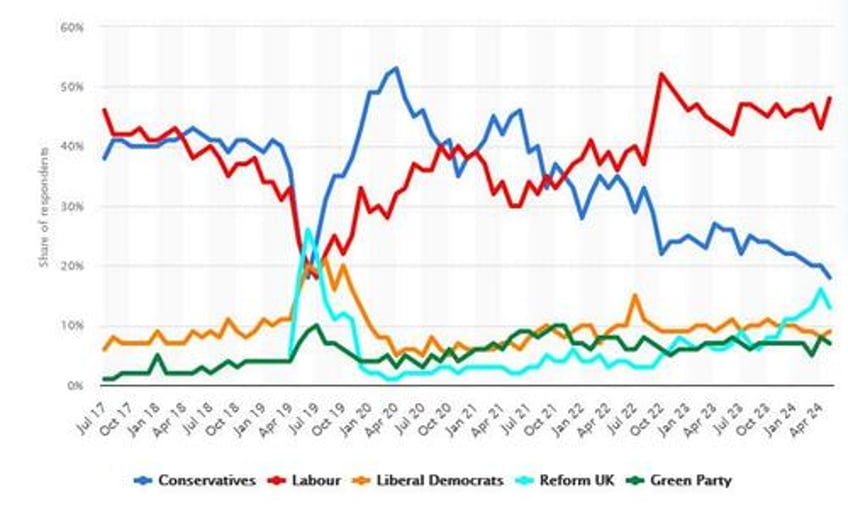

The polls indicate a landslide victory for the Labour Party, with a possible 200-seat majority over the Conservatives. Some polls show a +25% lead, others a 15-20% lead. Either way, it would be enough for a decisive Labour victory. It could be that the early election announcement will provide the Conservatives a slight boost, potentially at the expense of the Reform Party, but in our view it remains unlikely to significantly alter the overall outcome.

Markets hardly moved – this week’s inflation data and PMIs had a much larger impact. Indeed, one could easily make the argument that everything has been ‘priced in’ at this stage. And when examining the long-term historical performance of GDP, inflation, unemployment, sterling, or UK equity indices under various Conservative and Labour governments, it is indeed hard to identify any statistically significant differences that point to a clear advantage or disadvantage for either party.

However, in the UK, things can only get better. A fresh start under Labour could boost consumer, business, and investor sentiment. The UK has clear prospects to effect change through policy. The potential is there: many of the UK’s strengths are inherent, such as its island location next to Europe, its cultural soft powers, its moderate climate, its reasonably large population, or its language as the lingua franca. And many of its challenges are a matter of choice, such as planning, infrastructure, housing, and of course Brexit. This indeed still represents a self-inflicted issue that continues to harm the economy. The fact that Wednesday’s inflation news (2.3%, still higher than expected) is being used as a campaign talking point is concerning in and of itself.

A decisive victory for Starmer’s Labour would indicate there is limited public appetite for sustained, entrenched polarization on all sorts of issues, including economic ones. In our view, a government that acknowledges this general fatigue with conflict will create better policies. Such a shift to boring-but-better would then be beneficial for UK assets, lowering its risk premium relative to jurisdictions where this isn’t taking place.

Now we’re at it, let’s dig a little deeper still. The post-Brexit economic and political landscape shows the UK experiencing “deconvergence,” where it is trailing and falling behind some of its peers in various ways. It has led to higher UK-specific risk premiums. The idea of solving deconvergence was a central theme in Shadow Chancellor Reeves’ Mais Lecture. In that lecture, she contended the UK is currently in a moment of flux, with general agreement that laissez-faire economic strategies have failed but a new consensus yet to be formed. It is exactly within this state of transition that the potential for substantial shifts in an economic framework exists.

Reeves advocated for comprehensive supply-side reforms, a package she calls Securonomics. We’ll have to wait for the election manifesto to see real policy proposals, but she envisions an economy bolstered by the government’s proactive involvement, steered by a three-pronged strategy encompassing stability, investment, and reform. She argues:

- Stability should entail establishing a consistent economic and regulatory climate conducive to investment and expansion, which includes managing inflation, complying with fiscal rules, and providing clear policy direction.

- Investment needs to be galvanized through increased public-private partnerships within the framework of a green industrial strategy, augmented by government-led infrastructure expenditures.

- Reforms should unleash the workforce’s potential by tackling inequality, enhancing education, and promoting skills development, while the overhaul of institutions, planning systems, and governance structures should facilitate progress.

Labour’s economic ideas are strongly influenced by economist Dani Rodrik’s concept of “productivism”. This stresses the spread of economic opportunities to all regions and segments of society, with an active role of the government in steering towards this goal. It diverges markedly from neoliberalism by de-emphasizing markets and prioritizing the creation of quality, productive employment. Such an economic model is also skeptical of large multinational corporations and of globalization.

The implication is that Labour will try to reshape the economy to support national priorities, even if it means imposing barriers to production, trade or finance that would otherwise be considered inefficient by global market standards. Protectionism could therefore be a feature of Labour’s economic policy, even as they don’t want to label it that way. It also requires a higher inflation tolerance, as it tries to effect change in an economy that is already supply-constrained.

This would lead to an acceleration in nominal GDP, through a combination of growth and inflation – of course you’d hope to see more of the former than the latter. That is a positive factor for sterling, but also one that keeps policy rates at a higher level for longer. That’s not to say we won’t see a couple of rate cuts in the upcoming quarters, but it may leave the UK at a higher terminal rate than it otherwise would have had. We now forecast 3% ourselves. However, as we’ve seen in the US with Bidenomics, if done for the ‘right’ reasons, this is not necessarily a negative for risk assets.

Finally, if things can only get better, does this also mean a reversal of Brexit? No. Sure, we will see an overture towards Europe, with the UK-hosted European Political Community Summit on 18 July already being flagged as a first step of a charm offensive. And it’s also reasonable to expect more EU-UK cooperation across a spectrum of areas, predominantly in matters that tend to fly under the radar. However, the prospect of the UK’s reintegration into European markets, or even more formal arrangements like rejoining the Single Market, would be entirely inconsistent with Securonomics. That neoliberal flagship has sailed.