By Russell Clark, former CIO of Horseman Global Capital and author of the Capital Flows and Asset Markets substack

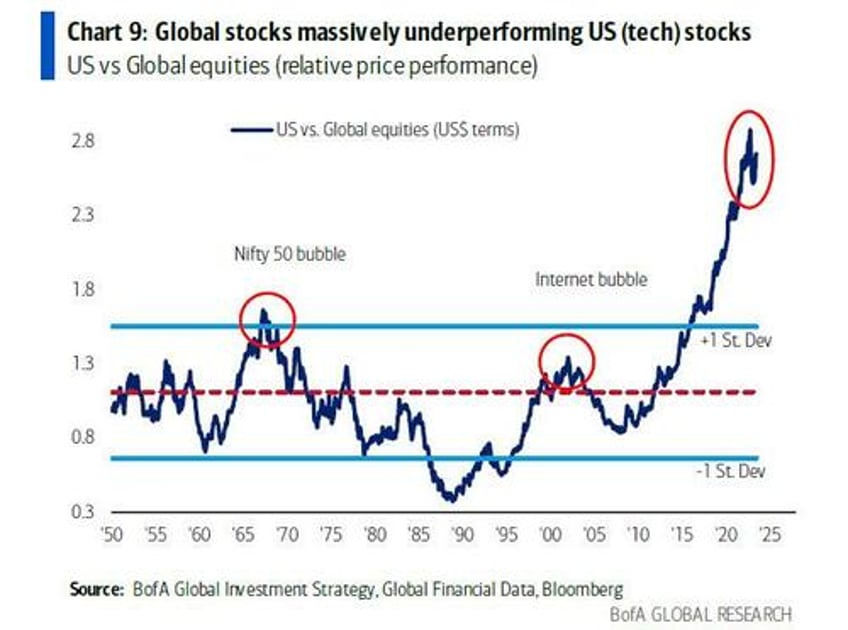

For professional fund managers, fading extremes was a very successful, if risky, investing and business strategy. At least in my working lifetime, from 1990 onwards, fund managers that faded the extreme of the 1980s Japanese bubble prospered. In 2000s, fading US and tech, while playing commodities and emerging markets worked best. However, trying to fade the US, and particularly US tech, has been foolish for quite some time.

Michael Hartnett of Bank of America produces “The Flow Show” report which is good. If you can access this, then most major investment banks can and do produce similar products. The one that is most important now, is the outperformance of US stocks to world stocks.

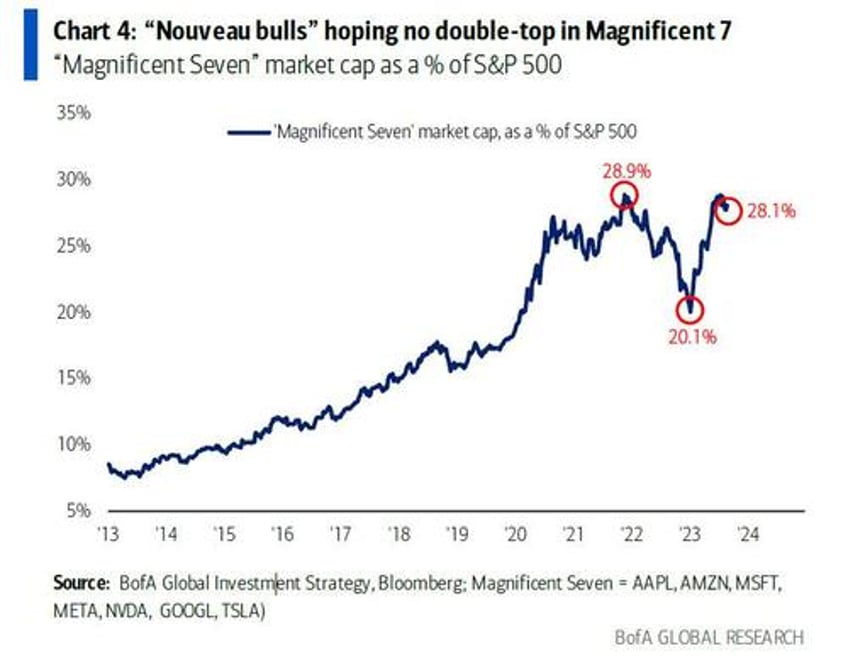

A more nuanced variation of this is the market capitalisation that is taken up by the “Magnificent Seven”. This in essence is saying that from 2016 onwards, these 7 stocks (AAPL, AMZN, MSFT, META, NVDA, GOOGL and TSLA) have dominated returns.

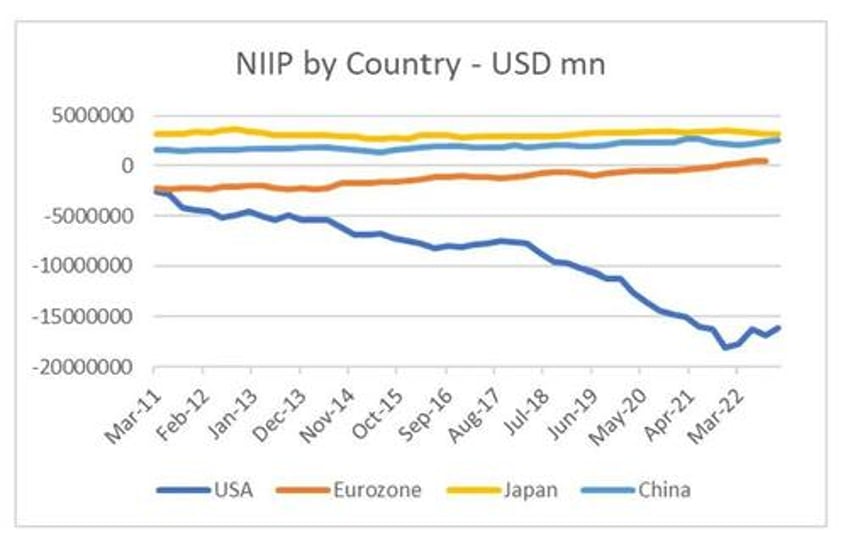

Historically, extreme investor bullishness would show up in net international investment position (NIIP), and much like the above charts has been pointing to extremes that should be faded since 2016. The Eurozone got into trouble when its NIIP was USD4 trillion deficit. the US has been well past that for over a decade.

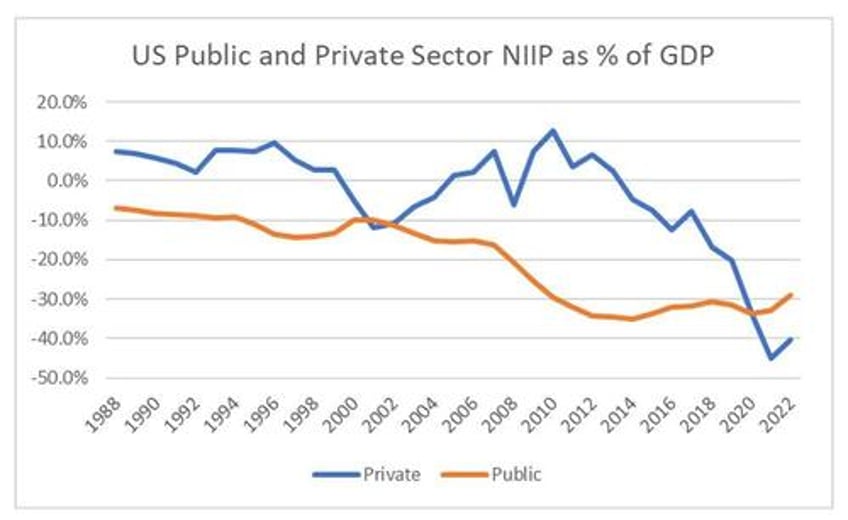

Even adjusting US NIIP for public and private sector extremes and GDP, we have been well past the private sector extreme seen in 1999. Fading extremes has become a losing strategy.

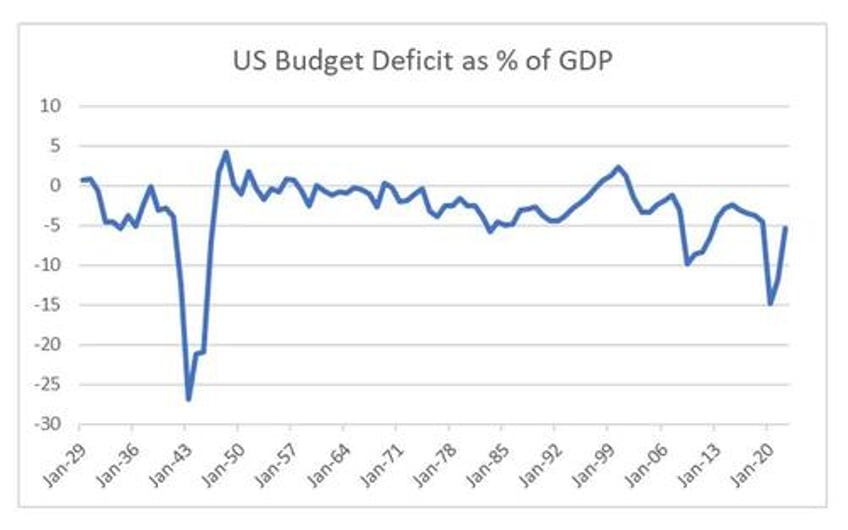

Why does fading extremes no long work? Well there are some other differences to this US bull market than to the others we have seen. It generates no fiscal surplus. In 1929, the US ran a fiscal surplus. Likewise in 1965, the Nifty Fifty bull market, and in 1999 during the dot com bubble. In 2023, we are looking at 5% of GPD deficit.

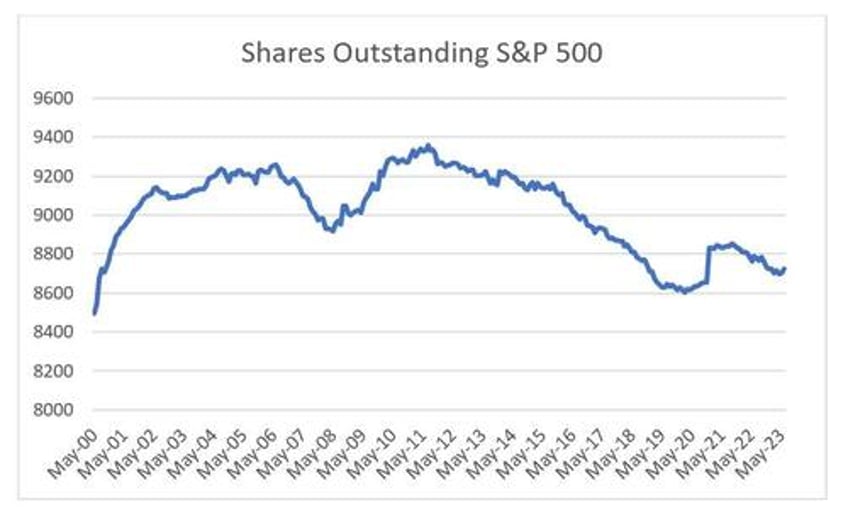

Another big difference is that shares outstanding in the S&P 500 is continuing to fall even as valuations and share prices continue to soar.

So how do we put all of these extremes into something that makes sense. Well as I have been pointing out, the US tax systems rewards US corporates for reducing its overseas tax, particularly in Europe. For tech companies, this is particularly easy to do, as core software and brands can be easily housed in tax friendly jurisdictions likes Ireland and Luxembourg. As more and more of the economy has moved digital, this means more and more of the corporate tax base has shifted to a “tax free zone”. This cash cannot be easily returned to US shareholders, as its offshore, but it can be used as collateral for loans to buy back shares. This has the added benefit of being tax friendly for shareholders. In essence. A large chunk of corporate profits are essentially untaxed, but the majority of the companies that have untaxed profits are listed in the US.

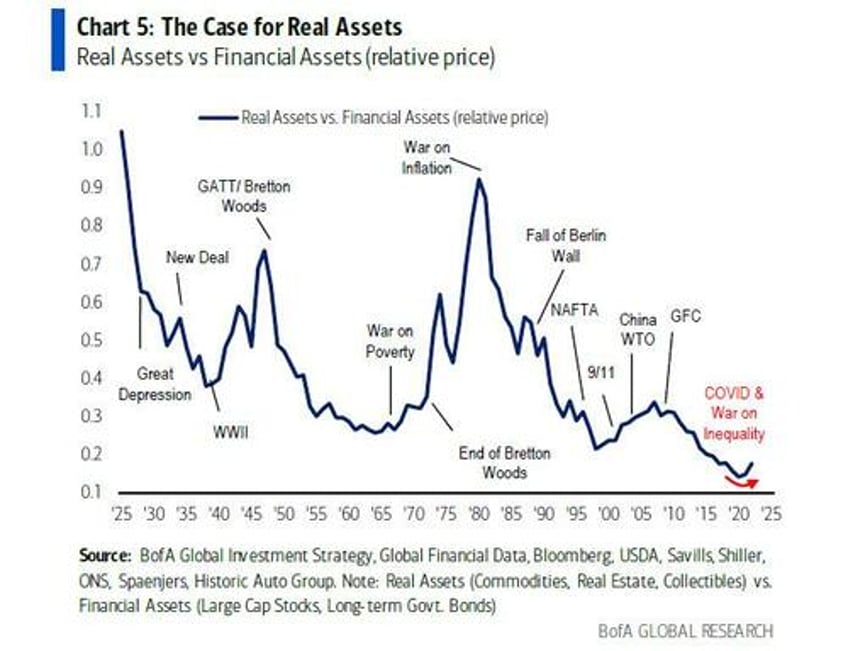

This means that even though we look at the Magnificent Seven as US stocks - they are in fact global stocks, that are based in the US for tax reasons. This means that US stocks will always outperform the rest of the world, and that valuation metrics mean little. Fading extremes is a failed strategy. In essence, the US capital markets increasingly dominated by the activities of international tax arbitrage and capital return in a tax efficient manner. And in many way, this realises the dream of both Reagan and Thatcher, and the pro-capital policies they instituted from 1980 onwards. But as Michael Hartnett adds in a chart, real assets have substantially underperformed financial assets. Buying financial assets with the rise of Reagan and Thatcher was very correct.

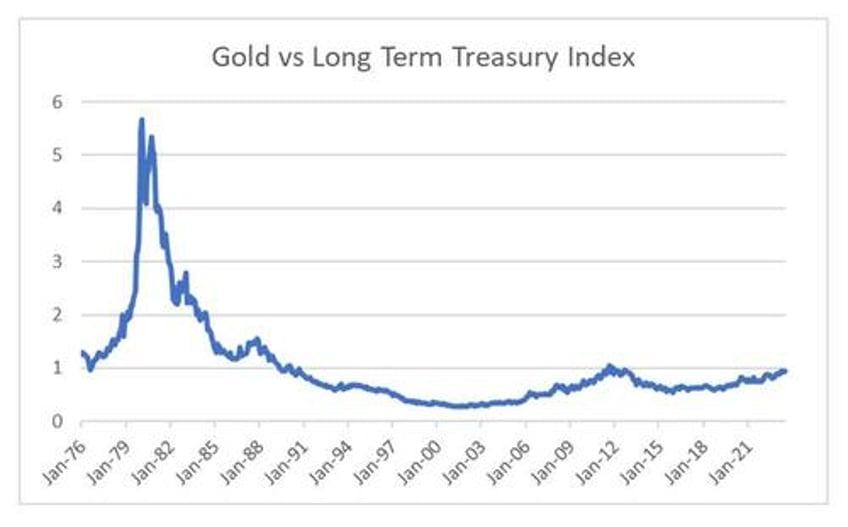

For me, I think this chart is too broad. The above analysis points to exactly the problem that the “pro-capital” trade suffers from. The richest and most successful firms pay little tax, and the richest and most successful people also pay little tax. As more and more business is digitised and moved into this “tax free zone” at some point governments will be forced to act. Most likely when the relative value of government credit deteriorates. For me, this is what the gold versus treasury return index is already indicating. This has a far more bullish (or bearish) chart that Hartnett’s.

One reason that US stocks continue to do well is that the magnificent seven have done a great job in pushing back government initiatives to tax them more, or to break them up (in stark contrast to China). But one day, politicians will have to choose between taking on corporates, or being voted out of power. And if there is one thing politicians love more than money, its power. Also corporates are violating my first rule of a happy life. Always give when you can, because if you force people to take, they take far more than you would have needed to give. US corporate tax policy is a short sighted policy that is headed for failure.