Interest-rate traders have managed to shake off the extreme conviction they had before the start of the year that the Fed would cut rates as soon as March.

Now, they are starting to ponder whether the central bank will have sufficient incentive to loosen policy in May.

While Jerome Powell reiterated his stance that a rate cut in the winter is unlikely in his much-anticipated CBS interview, anchor Scott Pelley remarked that the Fed Chair suggested the first cut could happen in the middle of the year -- even though it wasn’t to be found in the transcript of the interview.

And remember the interview was conducted a day before the release of the non-farm payrolls data for January, which showed the labor market expanded at almost twice the forecast pace, while the number for December was revised considerably higher. Not to mention that average hourly earnings growth showed an unexpected acceleration to 4.5%, hardly a number that is compatible with a headline inflation target of 2%.

If the Fed is convinced that cutting rates in March is too soon, Friday’s data set is unlikely to persuade the policy committee that May is the time to do it either.

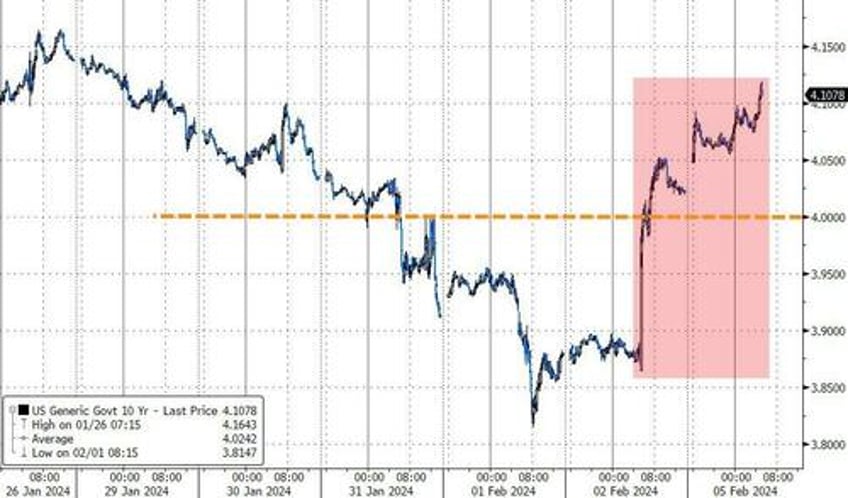

Little wonder that Treasury yields got a jolt after those numbers, but even after Monday’s follow-through increase, the correction isn’t done.

Fed fund futures, which were pricing in some 34 basis points of rate cuts by the time of the May meeting, now reckon about 20 basis points is all they can assign during that review.

It strikes me that unless the labor market goes into some kind of abrupt cataclysm, we may not get a rate cut in May, for the Fed is looking for incontrovertible evidence that the inflation genie is firmly back in the bottle. Inflation needs to be mellow for sufficiently long for the policy committee to act, and the strength of the jobs market together with earnings inflation doesn’t suggest that the smell test will have been met by then.

So it may well be that we get a rate cut in June, September and December — a trajectory that would be consistent with the Fed’s dot plot.