A friend’s mother was fond of saying there’s no good way to do a bad thing, and no bad time to do a good one. It’s true of public policy as of life generally, which is why both the public and politicians should talk more about principles and less about motives or tactics. And just as I was wrestling with applying this maxim to the current fiscal mess, someone Xed the classic Milton Friedman line to “Keep your eye on how much the Government is spending, because that is the true tax.”

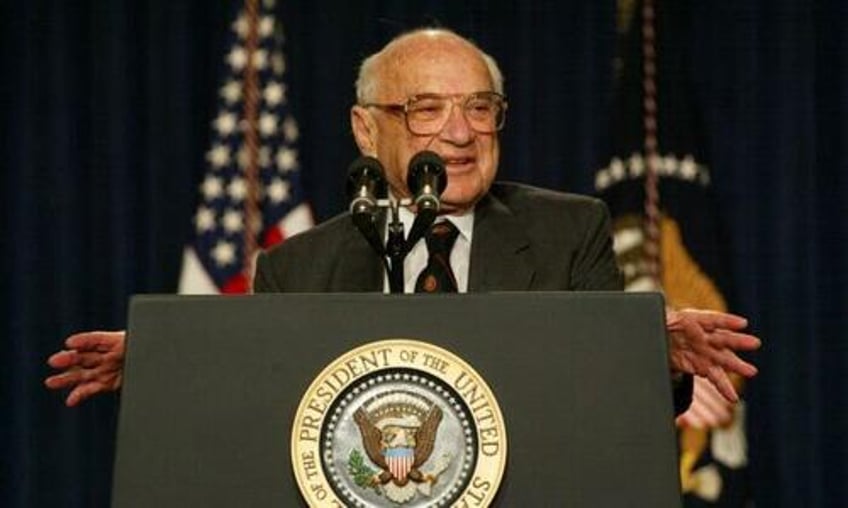

I’m not sure when Friedman said it. But he died in 2006 aged 94, and the clip shows him in middle age, so it was around half a century back. We should have listened, because it has applied consistently since and still does.

In fact, I’d just read a column by my former colleague Randall Denley about an administration of ostensibly conservative inclinations touting its “prudent, responsible” fiscal management while “tracking a clear path” back to a balanced budget from its current massive scary deficit. As Denley added tartly, “As it turns out, tracking a balanced budget is like tracking a unicorn. The tracking is easy, but finding one is hard.”

Indeed. Or at least indeed re the finding. The tracking isn’t as easy as it ought to be, because government budgets are infamously tangled forests of accounting conventions, focus-grouped prose, economic projections, and jiggery-pokery regarding long-term liabilities. And because neither the authors nor most of the audience adhere to Friedman’s wise words about what exactly we should be keeping an eye on as we navigate these deep dark woods.

As was his wont, Friedman compressed much potentially complex truth into short, clear, vivid words, immediately adding, “There is no such thing as an unbalanced budget.” Which is not addled but Chestertonian in its paradoxical brilliance because, Friedman went on, “You pay for it either in the form of taxes, or indirectly in the form of inflation or debt.”

Exactly. The budget is, by definition, balanced by one of those proper accounting conventions that says for every dollar of assets in the ledger there must be a corresponding dollar in liabilities, and vice versa. Thus, what looks like cash the state dropped from heaven as we wandered the desert beyond the Red Ink seeking the promised land of social justice, is actually offset somewhere by something. It must be. There’s no magic money tree in Ottawa, in Washington, in Toronto, in Victoria, or for that matter in Moscow, Beijing, Pyongyang or Teheran. Whatever governments spend, they must take in somehow.

This maxim does not, of course, necessarily mandate my own preferred minimal “night watchman” state that defends the realm, suppresses force and fraud, and otherwise leaves adults to work out their own salvation in fear and trembling or whatever décor and mood seems best to them. But it does require that we discuss what the government is doing, and weigh its costs against its benefits, with a clear sense of what both entail.

The benefits of public spending, or especially regulation, which takes and uses property in ways harder even to track than, say, the long-term debt of Ontario Hydro, now lurking in the books of the Ontario Electricity Financial Corporation that I doubt one voter in 100 has heard of, are rarely as great as proponents claim. And they are especially hard to measure when expressed in vague “The return on that investment in terms of what that will do and what it will pay for will be tremendous” decades later verbiage or “those are where the jobs are going to be, not just a couple of years from now, but a decade from now, a generation from now” rhetoric. How politicians know where jobs will be a generation hence is not obvious. But I digress.

The point is, there is a fairly clear way of measuring the cost. At least there would be if we were straightforward in our accounting and in our approach to funding, and put all spending into the on-book budget and all liabilities into the on-book debt. As Friedman also said, and this one I know was in 1977, “The true cost of government is what government spends, not what is labeled as ‘taxes.’” Shifting it to borrowing, the central bank printing press, or some “Crown corporation” doesn’t make it less burdensome. It just makes it harder to grasp and discuss, which makes it more burdensome partly because we can be persuaded, or can persuade ourselves, to ignore it longer.

So here’s my plea. In debating what government should attempt, and how big it should be, let’s agree that its real size, its real cost, is what it spends, and keep that side of the ledger as clean and clear as humanly possible.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.