By George Lei and Jacob Gu, Bloomberg Markets Live reporters and analysts

Russian President Vladimir Putin traveled to China for the Belt-and-Road Forum this week in a rare trip abroad after an arrest warrant was issued against him by the International Criminal Court. While the visit is full of political symbolism, it’s also taking place in the context of booming trade links between the two countries.

Twenty months into the Ukraine war, Beijing and its northern neighbor have become more economically entwined than ever before. The trend looks inevitable in the years — if not decades — to come, despite some degree of reservation on the part of Moscow.

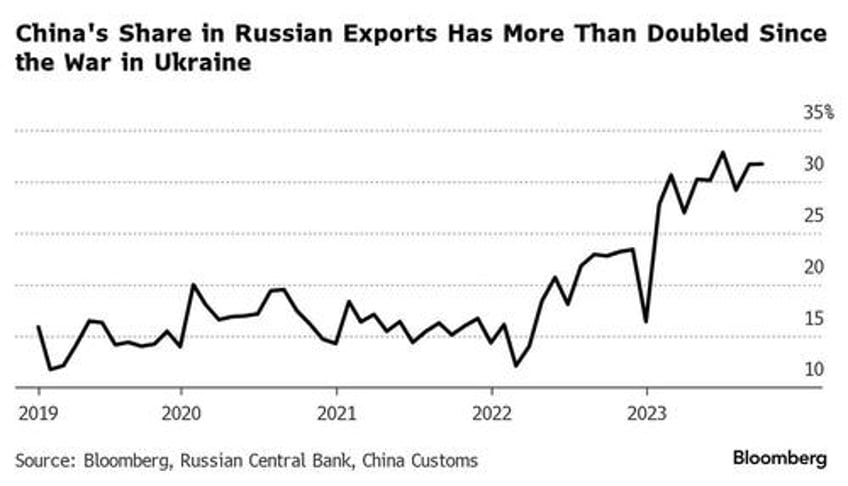

Prior to the war in Ukraine, China’s share of Russian exports had fluctuated in the 10-20% range for several years. Since February 2022, the share has more than doubled as Western sanctions crippled Russian commodity exports and multinational companies decamped en masse. China’s purchase of Russian goods surged in August by the most ever in dollar terms, with the country now accounting for roughly one-third of Russia’s merchandise exports. The interconnectedness, however, is still dwarfed by trade relationships in North America: Canada sends roughly half its exports to the US and the number is over 80% for Mexico.

The deepening ties are a winning proposition for China, according to Philipp Ivanov, a China specialist and senior fellow at the Asia Society in New York. Beijing gets access to Russian commodities and agricultural products at discounted prices while Chinese brands such as Huawei, whose operations are significantly curtailed in the West, expand their presence in a large market without significant competition. “The trend started well before the war and has accelerated afterward,” Ivanov said.

“A new Russia-China trade axis is forming,” Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance, tweeted early this week, citing a chart that shows a divergence in Chinese export growth between Russia and advanced economies. Even though the Kremlin understands the predicament, it doesn’t have a lot of choices with deepening economic dependency on Beijing, Ivanov noted.

China's exports to advanced economies (blue) are weak as global consumers front-loaded goods buying during COVID. So this weakness says nothing about western decoupling from China. But China's surge in exports to Russia says something; a new Russia - China trade axis is forming. pic.twitter.com/LlwWvZ0oHU

— Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) October 16, 2023

As of July, the Chinese currency accounted for over one-third of Russian imports and one-quarter of exports, according to central bank data. “Virtually all purchases by China of Russian oil, coal and metals are now settled in the yuan,” said Ivanov, who believes that even when the Ukraine war ends and sanctions are lifted, “the lessons learned from the economic blockade will endure among Russian policymakers.” With its pile of yuan cash, Russia has a wide plethora of Made-in-China products to choose from. That’s in stark contrast to trade with India, which is using its own currency to pay for Russian oil and leaving Moscow with billions of excess rupees with nowhere to spend.

Cooperation between the two is not always smooth. On Wednesday, President Xi pushed his Russian counterpart for a breakthrough in a new natural gas pipeline between both countries and Mongolia, seeking “substantial progress” as soon as possible. It appears like a win-win solution that helps China diversify its energy sources and lets Russia redirect natural gas from fields that used to feed Europe. Despite blessings from the very top, few details on the new pipeline emerged on Thursday as state-owned energy companies of the two nations signed a deal to boost gas supplies.

Still, the sheer size of China and demand for Russian resources means Beijing will remain an attractive market for Russia “for decades to come” and trade settlement in the yuan will likely stay in place, according to Asia Society’s Ivanov.