Says Italian American group, 'We look at Columbus Day as a symbol of the strength and motivation we needed to overcome obstacles'

The left’s annual hate on Christopher Columbus Day

Laura Ingraham discusses the left’s yearly tradition to attempt to kill Christopher Columbus Day on ‘The Ingraham Angle.’

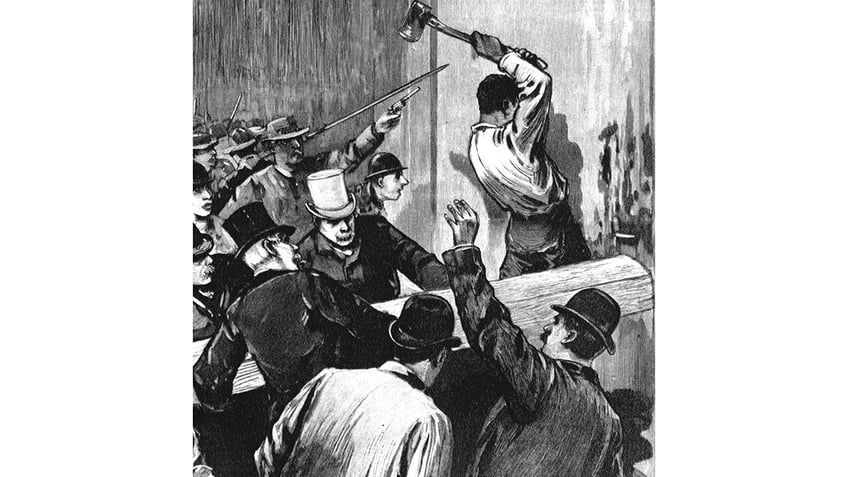

The story of Columbus Day was written with the blood of 11 Sicilian immigrants, who were savagely lynched by an angry mob in New Orleans in 1891.

"Most of them had been shot through the brain," The New York Times reported in a front-page story on March 15, 1891, the day after the mass murders.

The bodies of several victims "were laid out in a row ... and made a horrible sight as they lay weltering in blood and brains."

Other victims were hung and their dead or dying bodies desecrated.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

The same publication also published an editorial that seemingly celebrated the vigilantes: "These sneaking and cowardly Sicilians, the descendants of bandits and assassins … are to us a pest without mitigations," the editorial said in part.

Yet domestic outrage and international pressure helped turn the horrific murders in 1891 into a powerful testament to the importance of multicultural tolerance in an immigrant nation.

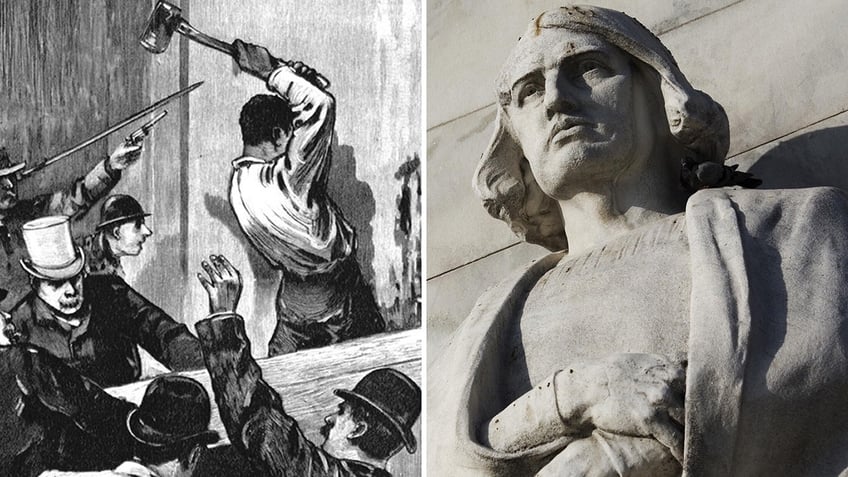

Portrayal of armed mob that stormed New Orleans prison and lynched 11 Italian immigrants on March 14, 1891. The outrage caused by the savage murders encouraged President Benjamin Harrison to proclaim the first Columbus Day in October 1892, the 400th anniversary of the famous first voyages to the Americas by Italian sailor Christoper Columbus. (Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

"Those who orchestrated and carried out the lynching went free, sparking a diplomatic crisis between the U.S. and Italian governments," Basil Russo, president of the Italian Sons and Daughters of America (ISDA), reported in 2022.

"To help resolve the issue and curry favor with Italian American voters, U.S. President Benjamin Harrison held the first national Columbus Day celebration in 1892, 400 years after the navigator’s historic discovery of North America," Russo also said.

The Italian Sons and Daughters of America (ISDA) is fighting the cancel-culture mob attempting to tear down statues of Christopher Columbus.

Russo's group, based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, has undertaken an "aggressive" effort in recent years, he told Fox News Digital ahead of this year's Columbus Day, to challenge the factually suspect woke narrative of the holiday and to fight the cancel-culture mob attempting to tear down statues of Christopher Columbus, a daring Italian explorer who reshaped world history.

The ISDA's effort includes several lawsuits, educational campaigns and even a demand that The Times retract and apologize for its congratulatory coverage of the savage murders.

The events of March 1891

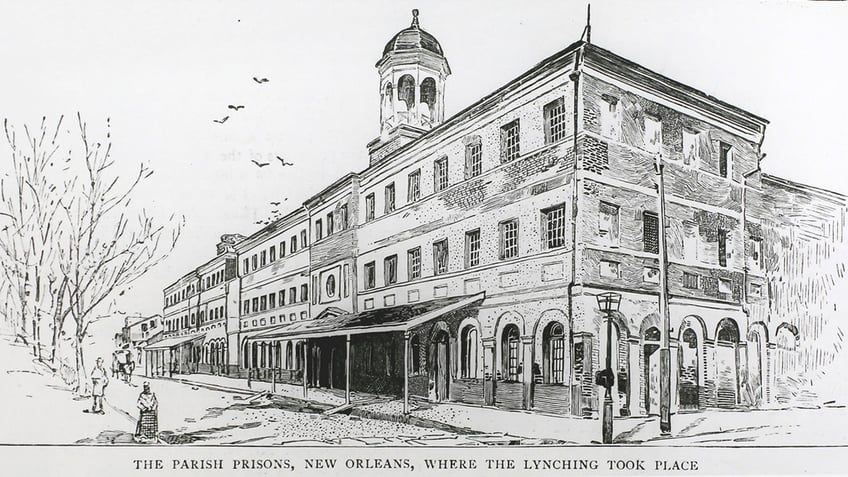

An armed, angry mob, numbering as many as 10,000 vigilantes, stormed Parish Prison on March 14, 1891.

Assault to the prisons of New Orleans and the lynching of 11 detainees — Italian Americans who were held responsible for the killing of David C. Hennessy, police chief in town, March 14, 1891. (SeM/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

They chased off cops "under a fire of mud and stones," smashed the prison doors with a massive wood beam and dragged out an unconfirmed number of men who were Italian and Sicilian immigrants.

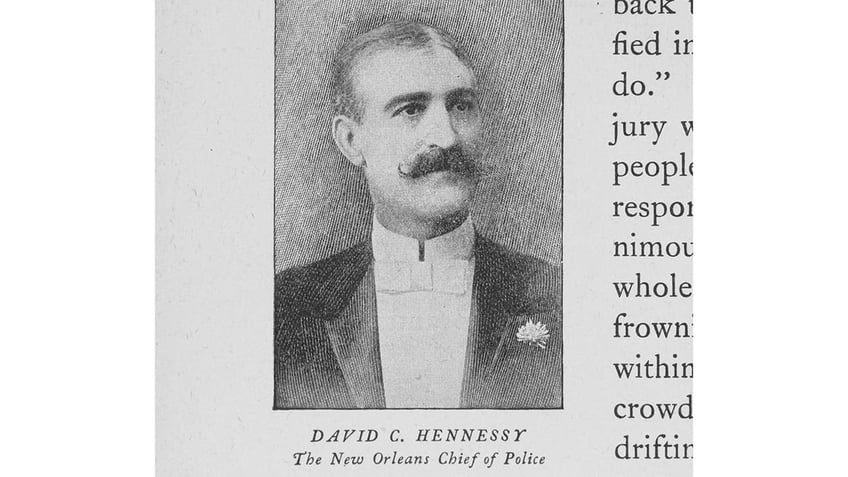

The mob was seeking revenge for the murder a year earlier of the city’s police chief, David Hennessy Jr.

‘PREHISTORIC FOOTWEAR’ WAS DISCOVERED IN SPANISH CAVE BY MINERS, SCIENTISTS REVEAL IN NEW STUDY

He reportedly uttered a highly offensive racial epithet toward the Italians in his last breaths, pointing a finger at the city’s burgeoning Sicilian immigrant community.

So many Sicilian immigrants flooded New Orleans in the years before that it became known as Little Palermo.

One lynching victim identified as "Polizzi" — most likely a street vendor named Emmanuele Polizzi — was shot in his cell before he was savaged by the mob.

"He was not killed outright and in order to satisfy the people outside who were crazy to know what was going on within, he was dragged down the stairs and through the doorway by which the crowd had entered," The Times reported of the carnage.

"To help resolve the issue and curry favor with Italian American voters, U.S. President Benjamin Harrison held the first national Columbus Day celebration." — Basil Russo

"A rope was provided and tied around his neck and the people pulled him up to the crossbars. Not satisfied he was dead, a score of men took aim at him and poured a volley of shot into him …"

Three of the men lynched by the mob were tried in the murder of Hennessy and acquitted; cases against two other victims ended in mistrial, according to the ISDA. Four other men were charged in Hennessy's murder and also acquitted, according to other reports.

A statue of Christoper Columbus was erected in Manhattan on Oct. 13, 1892. The towering New York City landmark stands at the intersection of Broadway and West 59th Street outside the southwest corner of Central Park, the area now known as Columbus Circle. The Columbus Day holiday, and Columbus statues, have faced growing challenges from officials in recent years. (Kerry J. Byrne/Fox News Digital)

Each man was returned to prison despite the lack of conviction, apparently part of a conspiracy to seek justice by other means, allegedly supported by local and state political leaders.

The conspirators acted fearlessly, announcing the gathering point in New Orleans newspapers, as The Times reported the following day.

"All good citizens are invited to attend a mass meeting on Saturday, March 14, at 10 o’clock a.m. at Clay Statue to remedy the failure of justice in the Hennessy case," the announcement read. "Come prepared for action."

The Times account of the murders was posted under the headline: "Chief Hennessy avenged," followed by a sub-headline proclaiming the guilt of the un-convicted victims.

Wrote Russo of the ISDA last year, "The horror of that night shocked the world, but today one will be hard-pressed to find the story in high school or college textbooks."

He told Fox News Digital this week, "We look at Columbus Day as a symbol of the strength and motivation we needed to overcome these obstacles and become assimilated into American society."

The Parish Prison, New Orleans, where 11 Italian and Sicilian immigrants were lynched by a mob on March 14, 1891. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

"It was established to help make Americans more accepting of immigrants. The Columbus controversy today has united all Italian American organizations."

Christopher Columbus gave the citizens of the United States a real historical figure from Italy whom they universally agreed was foundational to the events that led to the creation of the world’s first constitutional republic — and the first nation built upon universal ideals and the rule of law, rather than race, ethnicity or language and rule by force.

"We look at Columbus Day as a symbol of the strength and motivation we needed to overcome these obstacles and become assimilated into American society." — Basil Russo

As part of the group's effort to challenge the growing cancel-culture efforts to rewrite Columbus Day, ISDA attorney Michael Santo told Fox News Digital that he hand-delivered 30 packages to New York Times counsel in 2019.

The letter asked that the paper retract, explain and apologize for its 1891 coverage.

The letter from ISDA cited "the long lingering ramifications and the stain that the lynching left on the national Italian American community."

David C. Hennessy the New Orleans chief of police, 1897. Hennessy's murder in 1890 was blamed on Sicilian immigrants, 11 of whom were lynched by a mob seeking revenge in 1891. Their murders helped lead to the creation of a national Columbus Day celebration in 1892. Creator: Unknown. (Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images)

Santo said he did not receive a response.

In October 2019, five months after the letters were delivered, Brent Staples, a member of The Times editorial board, did write a lengthy feature under the headline "How Italians became 'white.'" It mentioned the lynchings.

The feature acknowledged and even quoted some of the publication's most racists statements in 1891 about the lynchings.

Leaders in Washington, D.C., appear to have taken notice of the Columbus Day origin story.

"Our own rattlesnakes are as good citizens as they," the paper wrote in 1891, as quoted by Staples. The Times added in its editorial from that year: "Lynch law was the only course open to the people of New Orleans to stay the issue of a new license to the Mafia to continue its bloody practices."

New York Times spokesperson Danielle Rhoades wrote on Sunday in a statement to Fox News Digital in response to a query on the topic, "Brent’s editorial makes it clear that we do not hide from past lapses. Instead," she added, "we cover them unflinchingly for our readers."

Biden administration mentions murders

Leaders in Washington, D.C., appear to have taken notice of the Columbus Day origin story.

The Biden administration has mentioned the New Orleans murders in its Columbus Day proclamations each of the past two years.

A mob smashed down the doors of a New Orleans prison in 1891 to kill 11 Sicilian immigrants. The outrage that this caused led to the first Columbus Day holiday in 1892. (SeM/Universal Images Group; and MANDEL NGAN/AFP, both via Getty Images)

"In 1891, 11 Italian Americans were murdered in one of the largest mass lynchings in our Nation’s history," the White House wrote in a statement on Friday.

"For so many people across our country, that first Columbus Day was a way to honor the lives that had been lost." — White House statement

"In the wake of this horrific attack, President Benjamin Harrison established Columbus Day in 1892. For so many people across our country, that first Columbus Day was a way to honor the lives that had been lost and to celebrate the hope, possibilities, and ingenuity Italian Americans have contributed to our country since before the birth of our republic."

Russo of the ISDA summed up what he said is the feeling of Italian-Americans across the country today.

"Don't take away our statues and don't take away our holiday," he told Fox News Digital.

For more Lifestyle articles, visit www.foxnews.com/lifestyle.

Kerry J. Byrne is a lifestyle reporter with Fox News Digital.