It Will Take 10 Years To Rebound

“Unless you know for certain that you can hold your investments, without fail, for the next decade at least, it’s time to sell… many of today’s top tech stocks will develop incredible products and grow revenue and profits substantially into the future. But… the cheapest of these high-quality businesses is trading at 25 years’ worth of profits. Most of this success has already been “priced in.”

I’m not saying stocks are going to crash tomorrow. But I think it’s very foolish to believe that stocks, on average, are likely to do well over the next decade.”

To explain further…

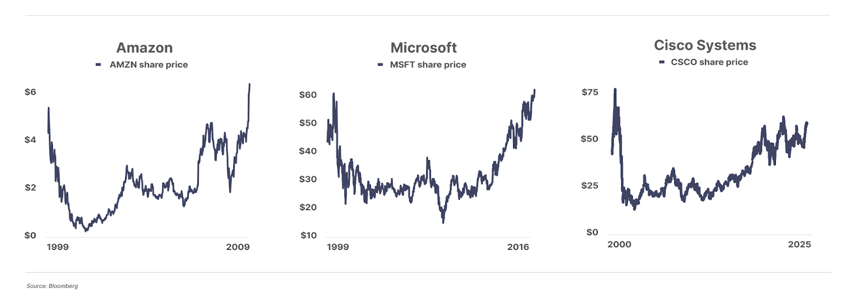

I believe we are at a multi-decade, perhaps even century-high, average level of equity prices. As such, I think it will take at least a decade for many of today’s S&P 500 members to “grow” into their current valuations. Consider, for example, the shares of Amazon (AMZN), Cisco Systems (CSCO), and Microsoft (MSFT) from the year 2000. The internet did indeed change the world. And those firms did indeed build virtually all of the critical infrastructure of the “new railroad.”

But, purchased at their peaks in early 2000, those stocks didn’t earn a dime for investors for years. Amazon’s share price didn’t recapture its 1999 peak until 2009… it took Microsoft 17 years to reclaim its 1999 highs… and today, Cisco shares are still 26% below their 2000 peak. That’s 25 years ago!

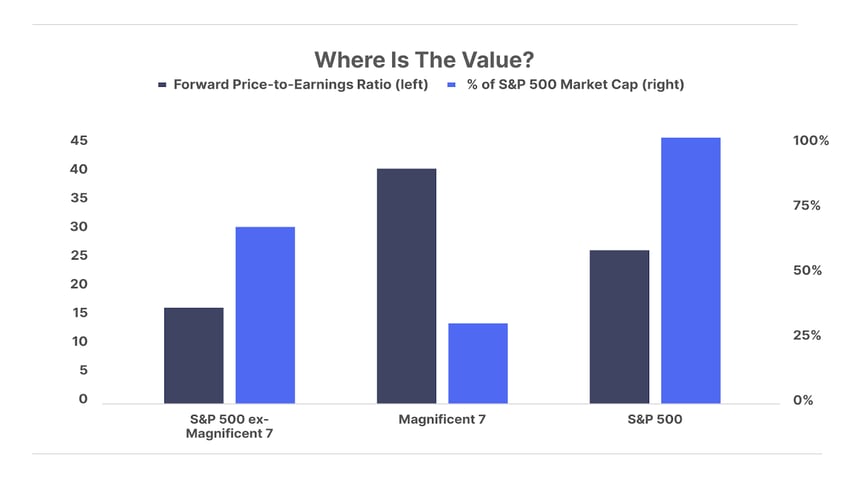

You should also remember that there are thousands of equities that trade on the various exchanges in the U.S. Not all of them are overvalued. In fact, as I pointed out, there are many businesses now out of favor that seem relatively attractive for investment.

Nevertheless, because so much capital is now being invested “automatically” in S&P 500 index funds and because so much of that index is now crowded into so few stocks and because those “Magnificent 7” stocks are very richly valued, a reasonable correction to those stocks’ multiples could easily trigger a panic that impacts all stocks, even those that are reasonably valued.

Right now, the Magnificent 7 account for 33% of the S&P 500 (that’s an historically unprecedented level of concentration of the biggest stocks). They trade at an average forward price-to-earnings ratio of 40. And the other 493 stocks in the index? They’re a relative bargain at a P/E of 17.

A sharp decline is likely not only because of the valuation issue, but also because I expect interest rates to continue to rise. I do not believe the government will be able to cut spending. And I think inflation is going to continue to increase to levels we haven’t seen since the 1970s.

But, whether I’m right or wrong about that, I believe the odds that stocks will continue to increase at 20% a year are very close to zero. And, the odds that, at some point in the next 10 years, stocks become vastly less expensive is pretty close to 100%.

So, I’m very confident in this prediction. But, I do not have a crystal ball. I can’t tell you when. Nor can I tell you how high those stocks might go from here before they correct.

What I can tell you is what Warren Buffett did the last time the stock market was this overpriced: he raised a huge amount of cash by selling 21% of Berkshire Hathaway (!).

Let me tell you the story in some detail:

Buffett bought General Re in December 1998. The deal closed in March 1999 – about one year before the market’s ultimate peak, at 44x CAPE ratio. (CAPE is the Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings ratio of the S&P 500… it compares the market value of every stock in the S&P 500 to the net income of those businesses, on average, and adjusted for inflation, over the previous 10 years.)

At the time, General Re was the largest property & casualty insurance business in the U.S. and the third largest in the world.

Buffett spent 272,200 shares of Berkshire to finance the transaction, which was 21% of Berkshire at the time. The deal valued General Re at $23.5 billion. This was the largest deal Berkshire has ever done (as a percentage of its market capitalization). Buffett’s largest-ever insurance acquisition prior to General Re was buying the rest of GEICO (49%) he didn’t own. That was a $2.3 billion deal, in 1996. The General Re deal was 10x larger! In fact, General Re was an even bigger transaction than Buffett’s purchase of BNSF Railway 10 years later ($22.5 billion), by which point Berkshire was much, much larger.

In other words, this isn’t any ordinary deal. This was a freakin’ Hail Mary. This was a financial mayday call.

Why would he do this deal?

Because General Re held $24 billion in cash and securities, including its insurance “float.”

Insurance “float” are funds that are held in trust for the payment of insurance claims. You can think of this capital as being akin to bank deposits. The insurance company doesn’t own these funds, but it is allowed to keep all of the proceeds from investing these funds. And, assuming good underwriting, these funds will continue to grow, which means, they become a de-facto asset of the business, even if they’re not a legal asset of the business.

Buffett specifically made sure that General Re brought over only cash: he had the company sell its entire $20 billion equity portfolio (about 250 stocks!), which generated capital gains taxes of $1 billion. Buffett was buying cash (and short-duration fixed income.) And paying 21% of his company for it!

He was hedging his entire portfolio, without having to sell any of the stocks in his portfolio. (He did sell one stock – it was a terrible mistake – but he didn’t have to sell any.)

After the merger:

- Berkshire had a net worth of $57.4 billion

- Its portfolio of common stocks was valued at $37 billion

- It held $15 billion in cash directly, plus another $22 billion in cash “float”

Buying General Re, with stock, had the impact of increasing the amount of cash Berkshire controlled as a percentage of its equity portfolio to around 60%.

So, to summarize, the last time stocks were this expensive, Buffett altered his allocation substantially by adding around $20 billion in cash against $37 billion of equities.

He did so in a very clever way.

Perhaps there’s a way for you to raise more cash too.

Or, you could simply move 60% of your portfolio into very well-run insurance stocks, like W.R. Berkley (WRB). That would probably produce a similar increase in the amount of fixed income you hold, indirectly. (Insurance companies are generally valued by the size of their fixed income holdings, including float.)

What stock did Buffett sell? McDonald’s (MCD)! What a huge mistake!

Buffett knew it, and wrote about this mistake later: “… my decision to sell McDonald’s was a very big mistake. Overall, you would have been better off last year if I had regularly snuck off to the movies during market hours.”

Let me know what you think by sending comments to

Regards,

Porter Stansberry

Stevenson, MD

Get Porter in your inbox… Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, Porter Stansberry will deliver his Porter & Co. Daily Journal directly to your inbox. He puts his 25+ years of investment knowledge into every punchy, fresh, and insightful issue… that’s free, with no strings attached. Everything is uncensored, and nothing is off limits. To get the Daily Journal, click here