With chronic illnesses soaring across the United States, a group of doctors and nutrition researchers say it’s time to reconsider the foundation of American dietary advice—starting from the bottom up.

In a peer-reviewed paper published in Nutrients, the authors contend that the traditional carb-heavy diet has not only failed to safeguard public health but may be contributing to rising rates of obesity and Type 2 diabetes. They propose a new low-carbohydrate food pyramid designed for the vast majority of American adults showing signs of metabolic dysfunction.

Their model—built on protein, full-fat dairy, and healthy fats—challenges decades of federal guidance and reignites a long-simmering debate about dietary fat’s role in chronic disease.

Rethinking the Pyramid

The original food pyramid, introduced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1992, stacked grains at the base, fruits and vegetables in the middle, and fats and oils at the top.

Though replaced in 2011 by MyPlate—a graphic that uses a dinner plate divided into five food groups (fruits, vegetables, grains, protein foods, and dairy)—the original pyramid’s grain-centric emphasis still lingers in public messaging and perception.

The paper calls that framework outdated and potentially harmful. Its 24 authors, including physicians, dietitians, and metabolic researchers, say the traditional model overlooks growing evidence linking high carbohydrate intake to obesity, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses.

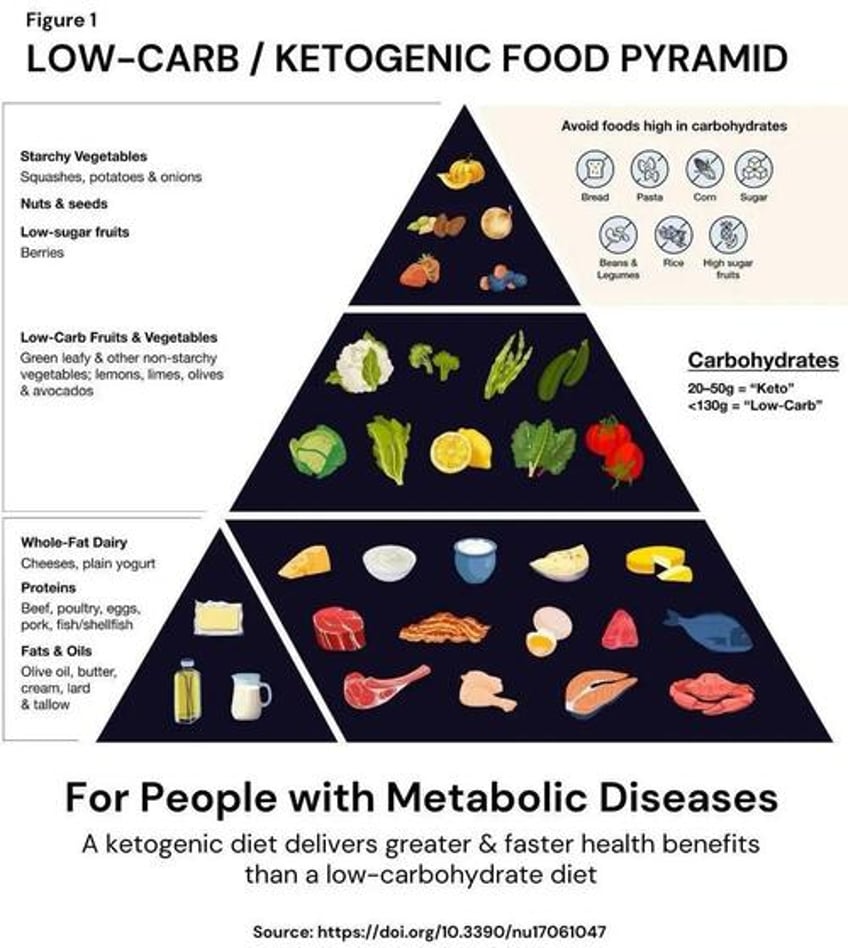

In its place, they introduce a striking alternative: the first low-carbohydrate food pyramid. At its base are foods once discouraged—meat, eggs, full-fat dairy, and healthy oils. Non-starchy vegetables and low-sugar fruits occupy the middle tier. At the top are starchy vegetables, higher-sugar fruits, and nuts, recommended only in limited amounts. Foods high in carbohydrates—such as grains, rice, beans, and added sugars—are excluded entirely.

The authors describe the model as both low-carbohydrate and ketogenic—terms they use interchangeably in the paper. A ketogenic diet typically restricts carbohydrate intake to between 20 and 50 grams per day, shifting the body into a fat-burning state called ketosis.

Source: Teicholz et al., Nutrients 2025

But some experts caution against treating all carbohydrates as equal. “Whole grains are associated with better health outcomes, while refined grains are the opposite,” said Alex Leaf, a nutrition writer with a master’s degree.

Current guidelines, he noted, blur that line by suggesting only “at least half” of grains be whole. “This framing dilutes what could be a clearer public health message.”

Supporters of the new model argue that most Americans already show signs of metabolic dysfunction and need dietary guidance that reflects that reality.

“This pyramid is for the 88 percent of American adults with metabolic diseases,” Nina Teicholz, the study’s lead author, told The Epoch Times. “The USDA food pyramid was created based on flawed scientific evidence and, when tested in clinical trials, has never been shown to prevent any chronic disease.”

Teicholz and her co-authors assert that the low-carb model aligns more closely with today’s science and better suits the nutritional needs of most Americans.

A Model With Deep Roots

For its advocates, the low-carb approach isn’t new—it’s a revival of therapeutic diets with deep roots in medical history.

“We have a long tradition in Western medicine for neurological conditions such as epilepsy (and both type 1 and type 2 diabetes treatment since the late 1700s) to be successfully treated without medications with ketogenic diets,” wrote Dr. Anthony Chaffee, a physician and nutritional medicine expert, in an email to The Epoch Times.

He also cited a 2005 Institute of Medicine report, which found no minimum requirement for dietary carbohydrates as long as protein and fat needs are met.

Chaffee pointed to early human history, noting that Arctic populations during the last Ice Age survived entirely on meat and fish, with no access to plant-based carbohydrates. “People live harm-free without carbohydrates generationally,” he said.

A Therapeutic Case for Cutting Carbs

The paper references thousands of clinical trials suggesting that low-carb, high-fat diets can improve insulin sensitivity, reverse Type 2 diabetes, and reduce reliance on medication.

Major health organizations—including the American Diabetes Association, Diabetes Canada, and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes—now endorse low-carb diets as one option for managing Type 2 diabetes.

The American Heart Association has similarly acknowledged that very low-carb diets, compared with moderate-carb diets, “yield a greater decrease in A1c, more weight loss and use of fewer diabetes medications in individuals with diabetes.”

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is a blood test that reflects average blood sugar levels over the past two to three months and is commonly used to monitor diabetes control.

The underlying biology is well known: Cutting carbs shifts the body into burning fat for fuel, a process called ketosis. This metabolic state also supports weight loss, as fat and protein increase satiety and often reduce overall calorie intake.

The authors say low-carb diets supply all essential nutrients—often in more bioavailable forms than fortified grains. They also cite evidence that the body can generate glucose on its own through gluconeogenesis.

“Many studies have established that people with chronic diseases suffer from carbohydrate intolerance,” the paper states. “Thus, in the same way that people with gluten intolerance avoid gluten, those with carbohydrate intolerance must limit carbohydrates.”

A Question of Fit—and Food Itself

While the study makes a strong case for low-carb eating, some experts warn against treating it as a one-size-fits-all solution.

“Many different kinds of diets support good health,” Marion Nestle, professor emerita of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University, told The Epoch Times. “The preponderance of evidence supports minimally processed foods that balance calories and include both plants and animal products.”

Nestle noted that nutrition studies are notoriously difficult and often reflect idealized eating habits. In reality, few Americans follow the food pyramid—or MyPlate. Most diets are dominated by ultra-processed foods high in added sugar, refined grains, and industrial fats.

Others question the long-term effects of cutting carbs so drastically. Anna Herby, a registered dietitian with the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, said that the low-carb pyramid lacks fiber, a key nutrient for digestion, weight management, and blood sugar control.

“All of these foods are high in saturated fat and cholesterol, two components of foods that are linked with heart disease, diabetes, dementia, and stroke,” she told The Epoch Times.

While low-carb diets can help manage Type 2 diabetes, some experts argue that the real driver is weight loss—not carb restriction alone. “A low-carbohydrate diet can be an effective tool,” said Leaf. “But it isn’t intrinsically superior. What matters most is finding something that a person can sustainably stick with.”

Nestle also raised environmental concerns, noting that low-carb diets often emphasize animal-based foods. “Beef cattle are the largest food contributors to greenhouse gas emissions,” she said.

The authors argue that low-carb diets don’t require heavy red meat consumption. They point to regenerative agriculture as one way to reduce the environmental footprint of animal-based foods. The EPA estimates livestock accounts for 3.9 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, though experts disagree on whether that figure overstates or understates the true impact.

Nestle emphasized that dietary advice should serve broad public health goals. While low-carb diets may help some people, she said, they shouldn’t overshadow a more inclusive message focused on whole, minimally processed foods.

Will Guidelines Change?

Despite a growing body of research on low-carb diets, it’s unclear whether it will impact the U.S. dietary guidelines.

In its latest report issued in December 2025, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) ranks legumes, beans, and seafood as preferred protein sources—placing red meat, poultry, and eggs lower on the list. It maintains support for low-fat dairy but stops short of taking a position on ultra-processed foods despite mounting evidence linking them to obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

Supporters of low-carb diets call the DGAC’s advice outdated. Critics, meanwhile, argue it reflects the best available science.

“I’ve seen large amounts of evidence supporting this approach,” said Nestle. “The diet proposed in this paper is not aimed at healthy people; it is aimed at people with metabolic diseases. Avoiding rapidly absorbed carbohydrates is a good idea for such people.”

Leaf also questioned the usefulness of a one-size-fits-all food pyramid. “It tries to cram everyone into a single box,” he said. “I’d like to see it recommend several healthy options geared towards different dietary preferences—standard, low-carb, vegan, etc.”

That raises a broader question: Should national dietary guidelines prioritize those already dealing with metabolic conditions—or aim to serve the general, healthy population?

“My one concern is that it will be interpreted as advice for everyone,” Nestle added. “The evidence still greatly supports diets that replace animal foods with plants—in variety—as a good approach. This does not change that.”

Teicholz sees it differently. She cites a University of North Carolina study estimating that 88 percent of Americans show signs of metabolic dysfunction.

“It should be the USDA-HHS food pyramid for people with metabolic diseases,” she said.

Chaffee argues that science isn’t the barrier—visibility is.

“No big company profits from people cutting carbs and getting healthy,” he said. “We don’t have multimillion-dollar ad budgets, drug reps in hospitals, or sponsored conferences to promote the data.”

He pointed to Australia, which recently designated ketogenic diets as “best practice” for managing Type 2 diabetes—proof, he says, that change is possible when the evidence is acknowledged.

With Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. overseeing this year’s federal dietary review, whether the recommendations will change remains to be seen.

However, as chronic disease rates rise, so does pressure to revisit long-held dietary assumptions. Whether or not the guidelines shift, the low-carb food pyramid has reignited the national conversation about what Americans should eat—and why.