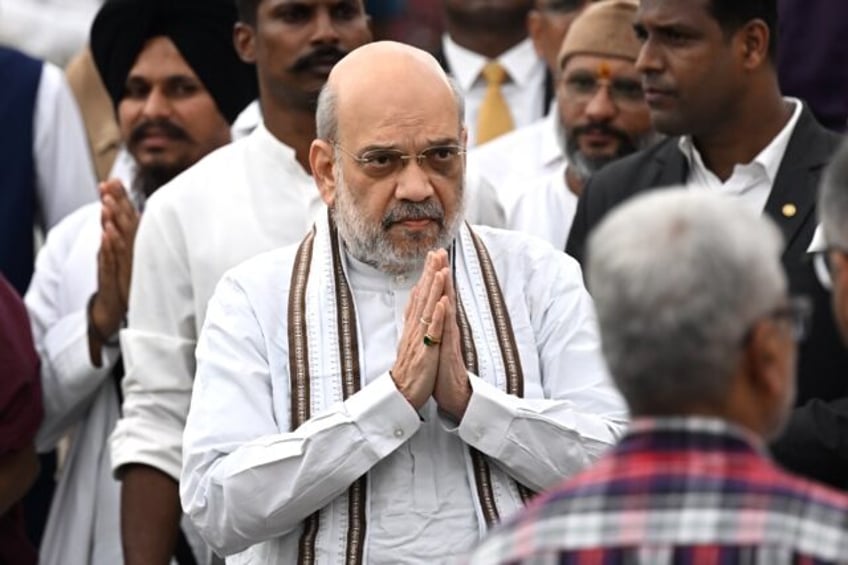

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s most trusted and important lieutenant, Amit Shah, has been accused by Ottawa of authorising attacks on Canadian Sikh separatists on Canadian soil.

New Delhi on Saturday defended Shah, who oversees the nation’s internal security forces as home minister, terming the allegations “absurd and baseless”.

Shah, 60, is often called India’s second-most powerful person after Modi, whom he has served loyally for decades, and has a fearsome reputation including accusations that he once orchestrated a series of murders.

Their enduring partnership has cemented the Hindu-nationalist worldview of their ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Modi is considered the charismatic frontman mobilising the masses behind the BJP, while Shah is seen as the enforcer keeping subordinates in line.

“The party is now completely dominated by Narendra Modi — and of course also by Amit Shah… who has been his right-hand man for over 20 years,” political scientist and India expert Christophe Jaffrelot said in 2024.

Both men began their political careers in Ahmedabad, the biggest city in the western state of Gujarat, where Modi took Shah — 14 years his junior — under his wing.

Modi was Gujarat’s chief minister and Shah was a junior lawmaker when in 2002 the state was rocked by some of the worst religious violence in independent India’s history.

A fire in a train carriage that killed dozens of Hindu pilgrims set off reprisals that killed at least 1,000 people, most of them Muslims.

Modi was accused of helping stir up the unrest and failing to order a police intervention — claims he denies — and the fallout saw him banned from entering the United States and Britain for years.

But the BJP won that year’s Gujarat elections in a landslide. Modi appointed Shah to the state’s powerful interior ministry.

Murder and exile

The following year was the start of a political storm that threatened to cut short Shah’s career.

Haren Pandya, one of Shah’s predecessors at the home ministry and an outspoken critic of Modi’s conduct during the 2002 riots, was shot dead during a morning walk in Ahmedabad.

The case was never officially solved but suspicion fell on gangsters Sohrabuddin Sheikh and Tulsiram Prajapati — both of whom were later killed by police in murky circumstances.

Critics claimed, but never proved, that Shah had ordered police to murder the pair.

Shah denied the allegations, saying they were concocted by political rivals to discredit him.

He was nonetheless arrested for the trio’s murder in 2010, forcing him to relinquish his ministerial posts, and spent three months in jail before he was granted bail by Gujarat’s top court.

Shah was banned from entering Gujarat for the next two years, prompting Indian media to dub him the “fugitive”.

All charges against Shah were dropped, months after Modi became prime minister in 2014.

‘Man of the match’

Shah made good use of his exile, taking up residence in India’s capital New Delhi and paving the way for Modi’s political ascent.

By the time Modi was announced as the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate for the 2014 elections, Shah had established a reputation as a masterful political strategist.

He was put in charge of the party’s campaign in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state with a bigger population than Brazil, where a near-sweep in the polls sealed Modi’s victory.

Modi afterwards called Shah his “man of the match” during the election.

He appointed him BJP president, later smoothing his entry into the national parliament and again appointing him home minister.

Shah was born in 1964 to a prosperous business family in the financial hub Mumbai, but moved to Ahmedabad where he studied chemistry.

He flirted with careers in banking and stockbroking, but found his true calling in politics, just as his future mentor Modi had in the same city years earlier.

Shah married his wife Sonal Shah in his early twenties and the couple had one son, Jay.

Jay Shah was appointed secretary of India’s cricket board aged just 31 in 2019, a rapid ascension to manage the country’s most popular sport that sparked accusations of nepotism.

He was elected unopposed to lead cricket’s world governing body five years later, a reflection of both India’s outsized sway in the sport and his reputation as an administrator.