'I hope I’ll never need to use it, but I’m prepared if I have to,' new gun owner says

Hamas hostage’s sister feels the ‘wind of change’ with Trump’s election

Yarden Gonen explains how President-elect Donald Trump’s victory gives hostages’ families renewed hope on ‘Fox News @ Night.’

In the delivery room of a hospital in Jerusalem, as the contractions intensified and the midwife tried to help the laboring woman shift to a more comfortable position, the mother felt something strange.

"She told me something was hurting her," recalled Erga Froman, the midwife. "Then I realized it was my gun, which was holstered on a rotating belt and had shifted forward, touching her." After the baby was born, Froman's colleagues at the hospital took a photo of her standing next to the newborn, still wearing the gun. "It's a picture of contrasts," she said.

Before Oct. 7, Froman, a mother of five now living in the Golan Heights in northern Israel, had never considered obtaining a gun license. Having opted to do non-military national service instead of military service in the IDF, she had never fired a gun in her life. The change came swiftly after Hamas’ unprecedented terrorist attack on Israeli communities on Oct. 7, leaving over 1,200 dead and shattering a sense of security that many Israelis had long relied upon.

TRUMP PROMISES 'HELL TO PAY' IN MIDDLE EAST IF HOSTAGES ARE NOT RELEASED BEFORE HE TAKES OFFICE

A civil emergency team practices shooting in the city of Kiryat Shmona, which is within the range of rocket barrages fired by Hezbollah from Lebanon, March 4, 2024. (Erez Ben Simon/TPS-IL)

"On the evening of Oct. 7, my husband and I realized that because I travel alone at night on dangerous roads to my job – bringing life into the world – I needed protection," Froman told Fox News Digital. "By the next morning, I had submitted my application for a gun license. Now I hope I’ll never need to use it, but I’m prepared if I have to."

For decades, firearm ownership in Israel was uncommon. Although military service ensured that many Israelis were trained with weapons, personal firearms were seen as more of a liability than a necessity. The strict licensing process deterred many, and Israelis trusted the state and its defense forces to protect them from terror threats, which took precedence over Israel’s low crime rates.

Midwife Erga Froman decided to get a gun license following the Oct. 7 Hamas terror attacks.

But after the Hamas massacre of Oct. 7, many Israelis began to see personal firearms as a necessary safeguard in a new and more dangerous reality. "As there weren’t enough medical teams on Oct. 7, there also wasn’t enough defense," Froman noted. "Learning from that, today we have a community medical team, and we are also armed to be able to give a first response."

Erga Froman, a midwife from northern Israel, and her husband decided to get gun licenses following the Oct. 7 terror attacks.

The Israeli Supreme Court is currently reviewing petitions against the nationalist National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, alleging that his office issued firearm licenses without proper authority.

In the months following the Oct. 7 attack, over 260,000 new gun license applications were submitted – nearly matching the total number from the previous two decades combined. More than 100,000 licenses have already been approved, marking a tenfold increase compared to the previous year.

A woman shoots at a range in the Jordan Valley, Israel, April 10, 2024. (Yoav Dudkevitch/TPS-IL)

Ayala Mirkin, a mother from Shiloh in Judea and Samaria, more widely known as the West Bank, applied for a firearm license after her husband, an IDF reserve soldier, was sent to fight in the war in Gaza, leaving her alone with their three young children. "I felt unsafe driving through Arab villages and knew I had to do something to protect myself," she said. "The process was much faster than it would have been before Oct. 7, but it still took months because of the flood of applications."

Mirkin now carries her pistol whenever she leaves her settlement, though she remains conflicted. "I don’t want to own a gun. The day I can give it back will be the happiest of my life. But I have no choice. It’s a tool for survival."

For families like Mirkin’s, firearms have become part of everyday life. She keeps her gun securely locked in a safe and has trained her children never to touch it. "It’s a tool for protection, not for killing," she emphasizes. "My focus is on preserving life, not taking it."

Oren Gozlan, a paratrooper veteran and father, is among those who hesitated before applying for a license. Living on the Israeli side of the Green Line border near the Palestinian city of Tulkarem, Gozlan decided he could no longer avoid arming himself. "The fear of having a gun at home with kids still exists, but the need to protect my family outweighs it," he says. "Oct. 7 changed everything. It brought the realization that we are vulnerable in ways we never imagined."

Gozlan is unnerved by what he sees as inadequate oversight in the licensing process. "At the range, I saw people who had never held a gun in their life, barely hitting their targets. It’s frightening to think these people are now walking around with firearms."

Saar Zohar, a reservist in an elite unit, expressed a similar shift. For years, Zohar resisted owning a gun, believing it unnecessary after his service. But a series of terror attacks following Oct. 7 pushed him to reconsider. "I couldn’t stand the thought of being helpless if something happened," he says. "Knowing I have the training and can respond, I feel it is my responsibility."

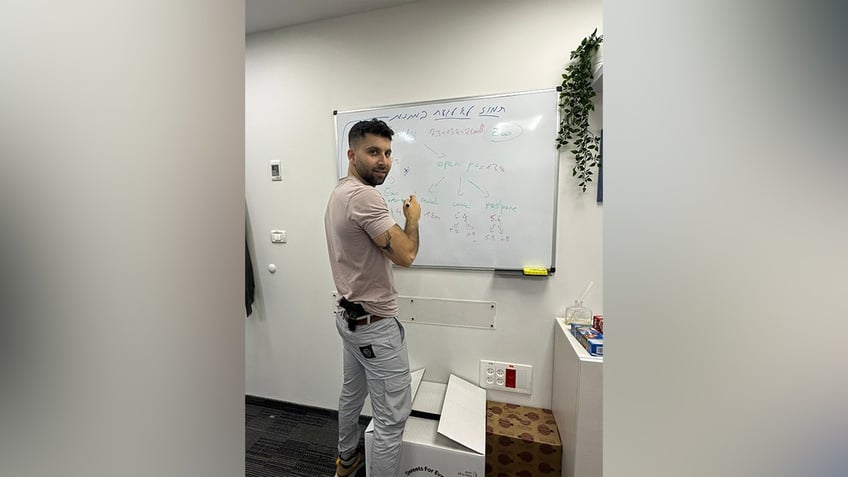

In the aftermath of the Oct. 7 massacre, Saar Zohar, a reservist in an elite unit of the IDF, decided to get a gun license. (Fox News)

Unlike in the United States, where gun ownership is often linked to fears of crime or the defense of private property, firearms in Israel are seen as tools for countering terrorism. Historically, Israel has avoided the public mass shootings that have sometimes plagued the U.S., but experts warn that the rapid proliferation of firearms could change this. With so many untrained individuals carrying weapons, the fear of impulsive actions and tragic mistakes looms large.

Zohar is haunted by the potential for misidentification. "The idea that another armed civilian might mistake me for an attacker terrifies me," he says, referencing a tragic incident in November 2023 when an Israeli civilian who had shot at terrorists in Jerusalem was mistakenly killed by a young soldier.

The psychological toll of this shift is evident among those newly armed. Eyal Haskel, a father of three from Tel Aviv, describes the social pressures he faced after Oct. 7. "I never wanted to carry a gun, but my friends questioned why I wasn’t armed. It felt like an expectation, almost a duty."

OCTOBER 7 HASN'T ENDED. ONE YEAR LATER, 101 HOSTAGES ARE STILL BEING HELD IN GAZA

Israelis train at a firing range, Feb. 12, 2023. (Gil Cohen-Magen/AFP via Getty Images)

But Haskel is also disturbed by what he has seen at shooting ranges. "People treat it like a game, firing without any understanding of the responsibility. It’s horrifying to think these people are now licensed."

For many Israelis, the reform represents a necessary response to an existential threat. Yet, it has also exposed deep flaws in the system. Critics argue that the current approach sacrifices long-term safety for short-term security, warning of potential unintended consequences, from accidental shootings to a rise in domestic violence.

SAVING LIVES ON 'DEATH STREET,' HOW AN ISRAELI KINDERGARTEN TEACHER BECAME A BATTLEFIELD HERO ON OCTOBER 7

"Getting a gun license is easier than getting a driver’s license," Gozlan says. "For a car, you need lessons, tests and strict rules. For a gun, it’s just some paperwork and a few hours at the range."

Froman sees things differently. "If someone threatens you, you only draw your weapon in a national security situation. You don’t pull a gun for personal life-threatening situations unless it’s a case of terrorists. The rules here are clear – you must have a safe for your weapon. I can’t rely on my husband’s safe; a firearm is personal. I’m not allowed to use his gun, and he’s not allowed to use mine. The regulations are very strict. The weapon is for defending against those who want to harm us, not for general self-defense."

An Israeli soldier patrols near Kibbutz Beeri in southern Israel on Oct. 12, 2023, close to the place where 270 revelers were killed by terrorists during the Supernova music festival on Oct. 7. (Aris Messinis/AFP via Getty Images)

Mirkin agrees. "We’re not like America," she said. "We don’t want guns as hobbies … for us, it’s survival, not choice."

One interviewee who asked to remain anonymous described how he trained his wife in basic firearm handling, even though she doesn’t have a license. "I never wanted to put her in this position, but if I’m not home during an attack, she needs to know how to defend our children."

As Israel adjusts to this new reality, the societal implications of increased firearm ownership remain uncertain. For many, the weight of these decisions highlights the delicate balance between protection and responsibility.

"I hope I’ll never have to use it," Gozlan says. "But I can’t ignore the reality we live in. Oct. 7 changed everything."

Efrat Lachter is an investigative reporter and war correspondent. Her work has taken her to 40 countries, including Ukraine, Russia, Iraq, Syria, Sudan, and Afghanistan. She is a recipient of the 2024 Knight-Wallace Fellowship for Journalism. Lachter can be followed on X @efratlachter.