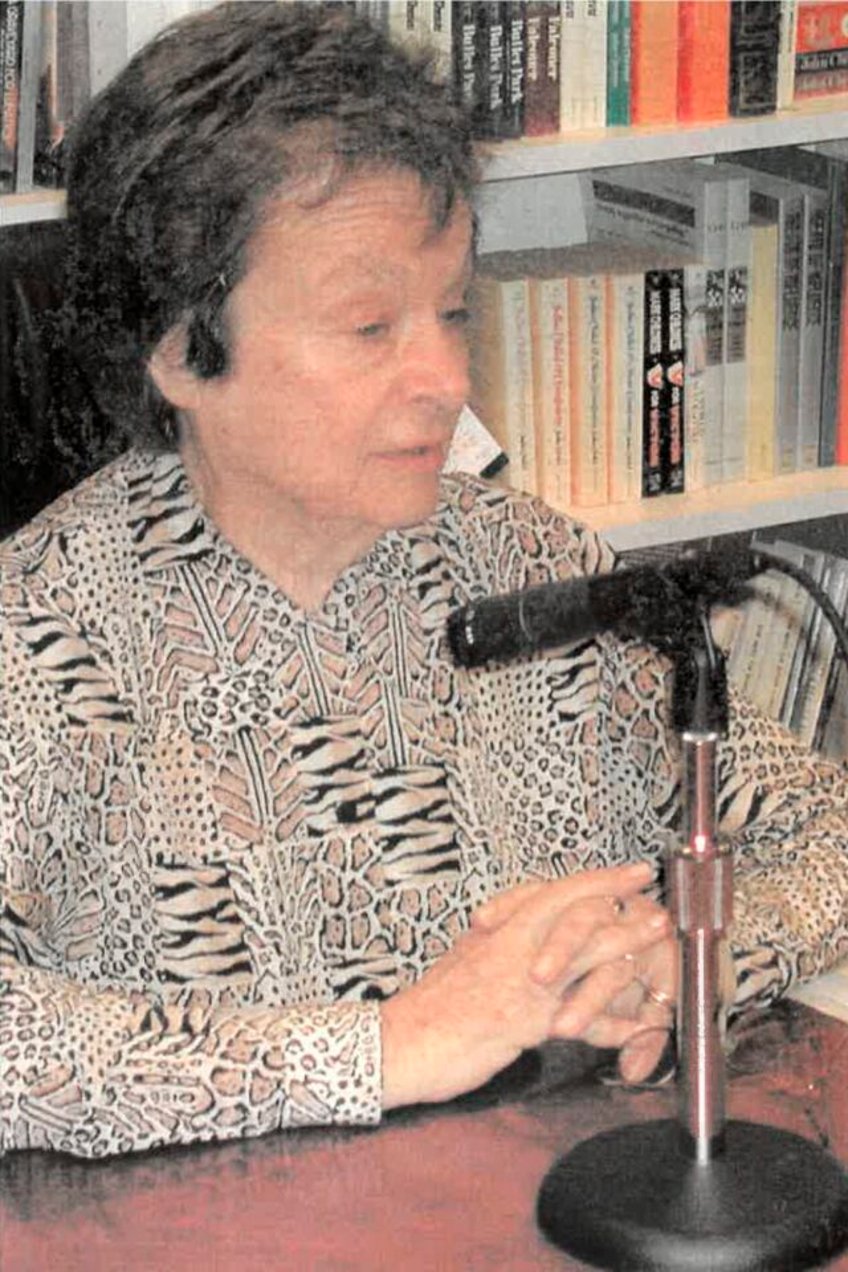

Betty Prashker, a pioneering editor of the 20th century who as one of the first women with the power to acquire books published such classics as Kate Millett’s “Sexual Politics” and Susan Faludi’s “Backlash,” died July 30 at age 99

Betty Prashker, publisher of the feminist classics ‘Sexual Politics’ and ‘Backlash,’ dies at age 99By HILLEL ITALIEAP National WriterThe Associated PressNEW YORK

NEW YORK (AP) — Betty Prashker, a pioneering editor of the 20th century who as one of the first women with the power to acquire books published such classics as Kate Millett’s “Sexual Politics” and Susan Faludi’s “Backlash” and helped oversee the careers of Jean Auel, Dominick Dunne and Erik Larson, among others, died July 30 at age 99.

Prashker died at a family home in Alford, Massachusetts, according to her daughter, Lucy Prashker, who cited no specific cause of death. At various times, Prashker held executive positions at Crown and Doubleday, both now divisions of Penguin Random House.

“Without Betty, there would have been no Crown Publishing as we know it,” a Penguin Random House executive vice president and publisher and former Crown publisher Tina Constable said in a statement Friday. “I am just one of many colleagues who benefited greatly from her experience, and from her unwaveringly championing advancement and higher pay for women in publishing.”

Born Betty Arnoff in New York City and a graduate of Vassar College, Prashker was a longtime bookworm, storyteller and tennis player whose life and career mirrored those of many women after World War II. She started out as a reader-receptionist at Doubleday in 1945, married labor lawyer Herbert Prashker in 1950 (they divorced in 1974) and took off the next decade to raise their three children. With the help of the emerging feminist movement of the 1960s, she returned to work and became an associate publisher. She had initially been turned down by Doubleday, in the early 1960s, but a few years later was unexpectedly asked to lunch by Editor-in Chief Ken McCormick.

“Doubleday doesn’t have enough women in top jobs,” Prashker remembered him telling her, as quoted in Al Silverman’s “The Time of Their Lives,” a publishing history. “And if we want to continue to do business with the government, we have got to do something in the way of affirmative action and have more women in our group.”

Back in the 1940s, Prashker had failed to convince Doubleday to take on a promising young writer she had met at a Greenwich Village party, James Baldwin. Now, her judgment was welcomed. In the late 1960s, she learned of a Columbia University graduate student writing a Ph.D dissertation on how women were depicted in Western literature. Prashker signed up the student, Millett, and published what became “Sexual Politics,” a cornerstone of second-wave feminism that Prashker would call an “educational experience for a dilettante like me.”

Over the following decades she would publish hundreds of books, including such hits as Larson’s “The Devil in the White City,” Auel’s “The Clan of the Cave Bear” series and Dunne’s “The Two Mrs. Grenvilles.” In the early 1990s, when she was editor-in-chief at Crown, she acquired a book on the anti-feminist wave of the previous decade that several other publishers had rejected, Faludi’s “Backlash: The Undeclared War Against Women.”

“My determined and devoted agent tried everything, including pitching the book as ‘a female “In Search of Excellence”’ (a long-running bestseller then) — with both of us praying no one would ask what that meant,” Faludi wrote on medium.com in 2014. ”In the end, the one person who was interested was Betty Prashker, editor-in-chief at Crown Publishers and, not coincidentally, a feminist pioneer.”

Not long after releasing “Backlash,” Prashker signed up an author whose first book had sold poorly and who was seeking a new publisher: Erik Larson had been working on an exploration of guns in the U.S., “Lethal Passage,” which Crown published in 1994.

“I first met with Betty in her office and after a while she started to get up and said ‘I have another meeting now,’ and I thought, ‘That’s it for me,’ ” Larson told The Associated Press during a telephone interview Friday. “But it turned out the meeting was for me. She leads me into a conference room and there all these people primed to work on the book — marketing, editorial, publicity, the whole deal. It was a terrific experience.”

Prashker remained as an executive at Crown until the late 1990s, when she stepped back and became an editor at large, continuing to work with Larson, among others. In 1998, her name entered film history when director Whit Stillman, who had previously worked at Doubleday, called one of the characters Justine Prashker in “The Last Days of Disco.”

She had earlier become part of legal history. In the 1970s, she noticed that many of her peers would take authors to the all-male Century Club, an elite gathering space in midtown Manhattan founded in the 19th century by James Fenimore Cooper and William Cullen Bryant, among others. Despite being sponsored by William F. Buckley among others, she was initially turned away, because, she was told, the club ″exists at the pleasure and for the pleasure of the gentlemen who constitute its membership” and that her request was “moot.”

But the Century Club was later found in violation of local anti-discriminatory law and reversed its position, in the mid-1980s. Prashker didn’t bother to reapply.

“It was the Groucho Marx idea,” she would explain for an oral history project at Random House, referring to Groucho’s famous quip that he wouldn’t want to join a club that had him as a member. “The important thing to do was to desegregate the place.”