The Biden administration announced on Tuesday that it will impose a 100 percent tariff—quadrupling the current 25 percent—on electric vehicles imported from China in 2024. In addition to EVs, the White House has significantly increased tariffs on Chinese steel and aluminum products, lithium-ion batteries, and solar cells.

“China’s using the same playbook it has before to power its own growth at the expense of others by continuing to invest despite excess Chinese capacity and flooding global markets with exports that are underpriced due to unfair practices,” Lael Brainard, director of the National Economic Council, told reporters at a call ahead of the announcement.

“China’s simply too big to play by its own rules.”

She added that the tariff increases are consistent with President Joe Biden’s China policy of “responsibly managing competition with China.” “We are working with our partners around the world to address our shared concerns about China’s unfair practices,” Ms. Brainard said.

The administration will make further adjustments to these tariffs as it obtains feedback from the private sector, consumers, allies, and China, according to a senior administration official on the call.

Chinese EVs Are Cheap and in Excess

EVs have been a strategic priority for both the United States and China.

For the White House, EVs are a centerpiece of its climate-related initiatives—achieving half of new car sales as EVs by 2030—and “Made in America” policy to boost the country’s auto manufacturing industry, a vital sector of the American economy.

After setting EVs as one of its priority industries a decade ago, the Chinese Communist Party doubled down at its annual plenary meeting concluded in March, calling EVs one of the “new productive forces.” Instead of changing its economy from investment-led to consumption-led, Beijing seems to be poised to export its way out of its current economic slump.

BYD electric cars for export waiting to be loaded onto a ship at a port in Yantai, in eastern China's Shandong Province, on April 18, 2024. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Heavy subsidies have driven China’s EV industry into overcapacity. Their prices are cheap, too.

China handed out $29 billion in EV subsidies between 2009 and 2022. Although the subsidies officially ended before 2023, other programs without “EV” in their names effectively continue the incentives. For example, Chinese media reported BYD snatching a third, or $1 billion, of the 2024 emission reduction subsidies from the Ministry of Finance.

As a result of 15-year-long subsidies, cheap Chinese cars have posed an “extinction-level” challenge to America’s auto industry, according to the Alliance for American Manufacturing, an advocacy group representing unionized steelworkers and other companies in the auto supply chain.

Driven by subsidies, China’s cheap EVs are also in excess.

Based on local government plans for the five years between 2021 and 2025, the China Center for Information Industry Development (CCID), an institution under China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, expects Chinese EV production capacity to reach 36 million in 2025.

With 15 million Chinese EV sales forecast for 2025, excess Chinese EVs will reach 20 million next year.

China knew about the overcapacity problem and had planned a way out. In a December 2022 report, CCID mapped out exporting cars to the European market. However, it also recommended building factories in Latin America to take advantage of the local incentives there to further expand China’s global EV market share.

In March, BYD, a Chinese EV maker, introduced the BYD Seagull, a mini EV hatchback. The starting price is 69,800 yuan in China, or about $9,650. In Mexico, the price is 358,800 pesos, or about $20,990. It’s still much cheaper than the cheapest EV—about $30,000—in the United States. The average EV price in the United States is about $54,000.

Overcapacity Becomes the Core Issue

Nazak Nikakhtar, former assistant secretary for Industry and Analysis at the Department of Commerce during the Trump administration, said that more would be needed to curb China’s overcapacity problem.

“The dynamic with the Chinese EVs is that they’re not coming directly into the United States. They’re flooding global markets,” Ms. Nikakhtar told The Epoch Times.

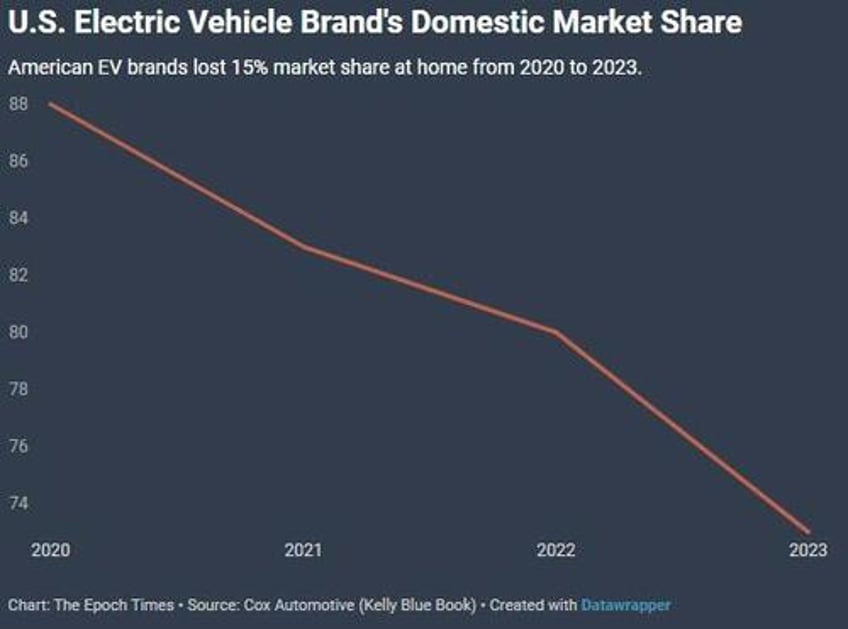

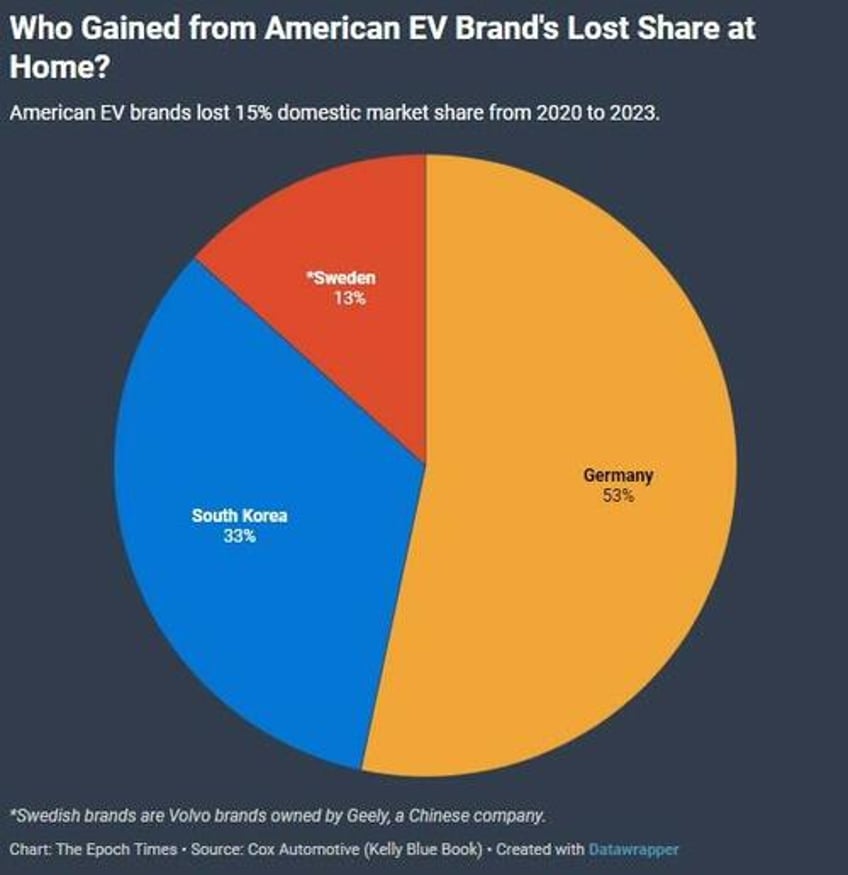

Currently, Chinese-brand EVs are not sold in the U.S. market. The Volvo brands owned by Geely, a Chinese company, had a market share of 2 percent in 2023. However, American brands lost a 15 percent home market share in the past three years, according to Kelly Blue Book, a vehicle valuation and automotive research company. The lost share was taken up by German and South Korean brands, and Swedish brands owned by Chinese.

U.S. Electric Vehicle Brand's Domestic Market Share

Chart: The Epoch Times Source: Cox Automotive (Kelly Blue Book)

Who Gained from American EV Brand's Lost Share at Home?

Chart: The Epoch Times Source: Cox Automotive (Kelly Blue Book)

“It’s the classic—China distorts all the other markets, and then they export their stuff into the United States in those import surges,” Ms. Nikakhtar said, adding that Washington needs to negotiate with Europeans, South Koreans, and Japanese to implement volume limits on their exports to the United States.

Last October, the European Commission began its anti-subsidy investigation on Chinese EVs to find ways to protect EV makers in the European Union.

During her trip to China last month, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen discussed the overcapacity issue, especially in green-energy sectors. She announced new dialogues with China’s Ministry of Finance and said the United States would “underscore the need for a shift in policy by China” in those talks.

Since then, Chinese media outlets have made coordinated attacks on U.S. concern over China’s excessive production capacities, calling it “protectionism.”

Other Tariff Increases

The Biden administration has levied new tariffs on Chinese port cranes and certain medical products. It will also triple tariffs on Chinese lithium-ion batteries, steel, and aluminum products to 25 percent this year and double the tariff on Chinese semiconductors to 50 percent by next year. The decision comes weeks after the White House called for tripling Chinese steel and aluminum tariffs.

These tariffs, initially put in place by the Trump administration in 2020, are up for review after four years, according to the “phase one” trade agreement between the United States and China. These “Section 301 tariffs” were imposed according to Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which authorized U.S. presidents to impose tariffs to counter international trade violations.

In a press call, a senior administration official said that upon review, the Office of the United States Trade Representative recommended no tariff reduction because “China has not eliminated many of the forced technology transfer policies and practices, and instead has even become more aggressive in some of those actions, including through cyber intrusions and cyber theft that harm American workers and businesses.”

In addition to commercial considerations, President Biden has also expressed national security concerns over Chinese cars. In February, he asked the Department of Commerce to investigate whether Chinese vehicles pose data or infrastructure risks to the United States.

Ms. Brainard at the National Economic Council highlighted the benefit of increased tariffs in two battleground states—Michigan and Pennsylvania—but a senior White House official said that the decision had nothing to do with election-related considerations. According to White House senior officials on the press call, because the tariff decisions were a follow-up on the Section 301 review, the Biden administration has not considered an outright ban on Chinese EVs.

The officials assured that these tariff increases will not affect inflation as they are “a very targeted set of tariffs on specific sectors.”