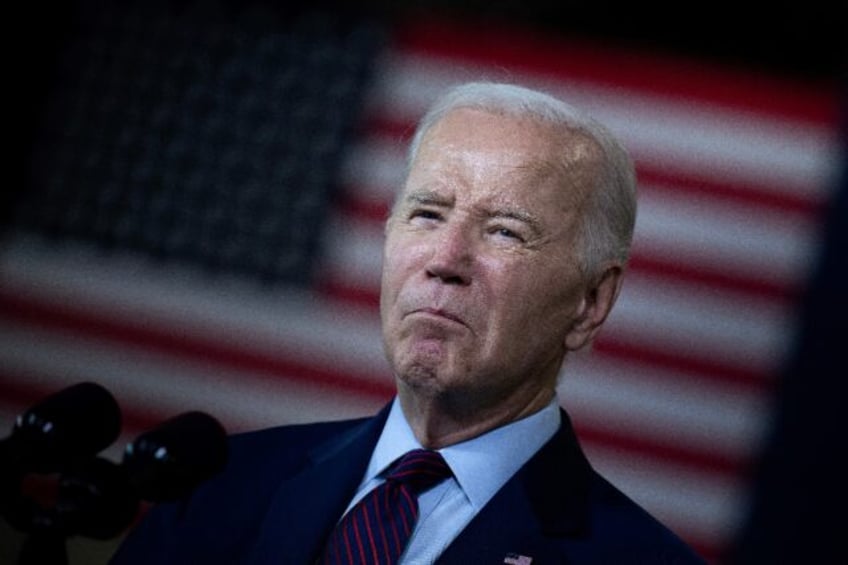

If he had it to do over, he would probably choose another name: A year on, Joe Biden is struggling to sell Americans on the benefits of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The hugely ambitious project is aimed at speeding America’s transition to clean energy, rebuilding its industrial might and increasing social justice.

On August 16, 2022, when the US president signed the $750 billion plan into law, the country was in the midst of a dramatic surge in prices that was battering the Democratic leader’s popularity.

So “the Inflation Reduction Act” seemed a logical name, even though the plan aimed largely — through some $350 billion in subsidies and tax credits — at speeding the transition to green energy.

“I wish I hadn’t called it that, because it has less to do with inflation than it has to do with providing alternatives that generate economic growth,” Biden said at a recent meeting with donors in the western state of Utah.

The previous day, the 80-year-old Democrat, who is seeking a second term in office next year, had inaugurated a sustainable energy project that he said symbolizes the best of the IRA.

That project, in nearby New Mexico, involves the construction of electricity-generating wind turbines on the site where a factory once made plastic dishes — in a state suffering the harsh effects of climate change in the form of wildfires and extreme temperatures.

Private investment

The White House says the IRA has spurred $110 billion in private investments in the clean energy sector since it became law — raising concern among Europeans and other allies with its stated ambition of industrial independence.

“This is the most significant climate and clean energy legislation in US history,” said Lori Bird of the World Resources Institute, an environmental group.

The incentives it provides “are designed to last for a decade,” and their effects “should last beyond that,” she said.

A study by nine teams of American researchers found that the IRA should reduce US emissions by between 43 percent and 48 percent by 2035 compared to 2005 levels.

That falls short of the official objective of halving emissions by 2030.

Reaching that goal, many activists say, will require not just the enticements of financial “carrots” but the threat of regulatory “sticks” — which could, however, face a major obstacle if they reach the conservative Supreme Court.

For now, Biden’s urgent concern is finding ways to capitalize before the November 2024 presidential elections on what he calls “Bidenomics.”

That term is meant to embrace both the current vigor of the US economy and a promising future built partly on the IRA but also on major investment programs in technology and infrastructure.

‘Going to take time’

Most Americans are only vaguely aware of the varied promises of these programs — supporting the development of quantum computing in the face of Chinese competition, building millions of electric cars while creating jobs, lowering the price of insulin and democratizing access to the internet.

“People don’t know the changes that are taking place are a consequence of what we did yet,” Biden told the Utah donors on Thursday. “And it’s going to take a little time for that to break through.”

The Republican Party has pushed back against Biden’s campaign, recently issuing a statement deriding his “desperate attempt to sell the so-called Inflation Reduction Act,” which it blasted as a “scam.”

Biden, however, has seemed to take pleasure in pointing out that Republican lawmakers don’t seem to have any problem accepting IRA funding when it pays for projects in their own districts.

On Wednesday, he even singled out a particularly virulent supporter of Donald Trump, Congresswoman Lauren Boebert.

Biden noted, with clear sarcasm, that the Inflation Reduction Act was helping pay for a huge wind-turbine factory in the Colorado district of this “very quiet Republican lady” who, like others of her party, had opposed the IRA.

“She railed against its passage,” Biden said, adding with a smile, “That’s OK, she’s welcoming it now.”