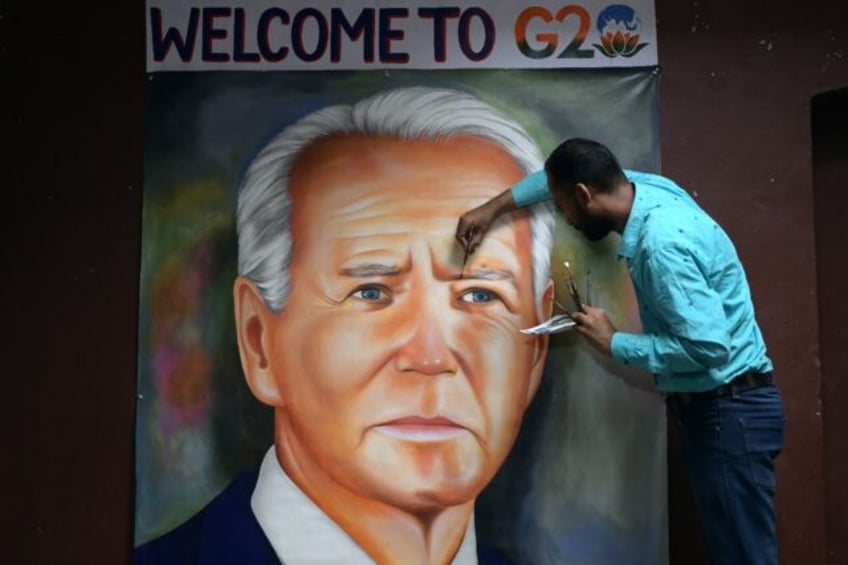

US President Joe Biden heads to India for the G20 summit this weekend aiming to capitalise on the glaring absence of China’s and Russia’s leaders to bolster alliances in the sharply divided bloc.

Deep disagreements on Russia’s war in Ukraine, the phasing out of fossil fuels and debt restructuring will dominate talks and likely hamper agreements at the two-day meeting in New Delhi.

Biden will discuss “a range of joint efforts to tackle global issues” including climate change and “mitigating the economic and social impacts of Russia’s war in Ukraine”, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said ahead of the summit.

China’s Xi Jinping, president of the world’s second-largest economy, will miss the meeting at a time of heightened trade and geopolitical tensions with the United States and India, with which it shares a long and disputed border.

Beijing also bristles at India’s membership in the so-called Quad, a security partnership with Australia, Japan and the United States that China views as an effort to contain its influence in Asia.

China has given no reason why Xi will not attend the September 9-10 summit, confirming only that Premier Li Qiang would join the leaders of the world’s biggest economies, which account for about 85 percent of global GDP and greenhouse gas emissions.

‘Worrisome’

Xi’s absence will impact Washington’s bid to keep the G20 the main forum of global economic cooperation and efforts to make a financing push for developing countries.

“Without China being on board… issues may not really see the light of day or reach any logical conclusion,” said Happymon Jacob, a politics professor at India’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

The ongoing war in Ukraine also overshadows the event, with Russian President Vladimir Putin set to miss the meeting and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov taking his place at the table.

In March, the International Criminal Court announced an arrest warrant for Putin over the war crime accusation of unlawfully deporting Ukrainian children, allegations the Kremlin insists are “void”.

“As long as Russia doesn’t end this war, there can be no business as usual”, German government spokesman Wolfgang Buechner said.

The global crises facing the bloc are “far more difficult, more complicated, more worrisome than it has been for a long time”, Indian Foreign Minister S Jaishankar told India’s NDTV news channel ahead of the meeting.

India, fresh from celebrating the cementing of its position as a space power by landing a craft on the Moon in August, has portrayed its hosting of the G20 as a coming-of-age moment that makes it a key global player.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has pitched India as a self-styled leader of the “Global South”, a bridge between developed and developing countries, and has pushed to expand the bloc into the “G21” with the inclusion of the African Union.

Tackling climate change

Modi has tried to use the G20 to build consensus among key economies to reform global multilateral institutions like the United Nations to give a greater say to developing countries such as India, Brazil and South Africa.

“India’s emergence as the world’s fastest-growing economy and its inclusive approach is good news for the Global South”, said Sujan Chinoy, a former Indian diplomat and head of the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses.

Modi’s efforts to urge G20 leaders to sidestep deep divisions to address critical global issues have been unsuccessful in ministerial meetings ahead of the summit, including global debt restructuring efforts and commodity price shocks following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

A G20 energy ministers’ meeting in July failed to agree on a roadmap to phase down the use of fossil fuels — or even mention coal, the dirty fuel that remains a key energy source for economies like India and China.

Against a backdrop of record-breaking temperatures and deadly heatwaves across the globe, climate activists have warned of dire consequences — particularly for developing countries — if leaders fail to forge a consensus in New Delhi.

India and China are among the biggest global polluters but argue that historical contributors in the West need to take a much bigger responsibility for today’s global climate crisis.

The G20 energy and climate consensus push has also faced resistance from countries like Saudi Arabia and Russia, who fear that a transition away from fossil fuels would dent their economies.