The Talmud, the central text of Jewish law, takes more than seven years to finish, if you study one double-sided page per day — and on Wednesday, I finished it where I began in 2017.

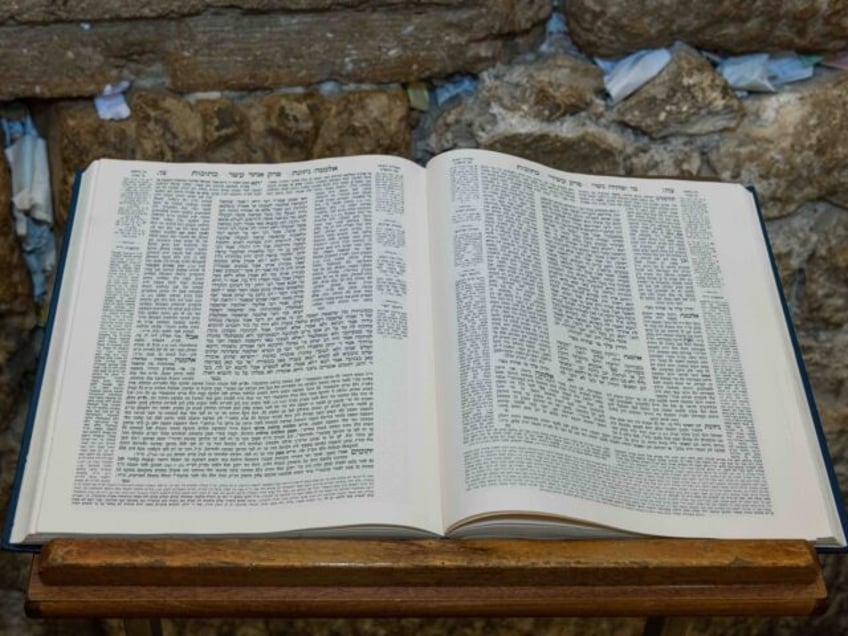

There are actually two Talmuds, both compiled roughly 1500 years ago — one by exiles in Babylonia, and one by Jews who remained in Israel, known as the Jerusalem Talmud. Each documents what is known as the Oral Law, which is a set of interpretations that accompany the Torah, and which religious Jews believe was given to Moses on Mount Sinai along with the written law. The Babylonian Talmud is better organized, and thus is more widely studied and cited.

Why did I do it? It’s a very interesting question.

I attended a somewhat liberal Jewish school from second through eighth grade, where I was exposed to a bit of Talmud, but opted to go to my local public high school instead of the religious one. The public school had a better science program and a much wider variety of sports; the Jewish high school only had basketball. I knew I would be missing out on the religious studies that I enjoyed, but resolved that I could make up for the gap somewhat later.

“Later” turned out to be the year after I graduated from Harvard, when I spent six months in a yeshiva — a seminary — in Jerusalem, at one of the few Orthodox institutions where men and women study together.

It was wonderful, but I was restless. I was, frankly, a little tired of school. I had little patience for the intricate debates of Jewish law, and slipped out frequently to smoke hookahs in the Muslim Quarter or write in my journal at the bustling Café Hillel.

Years went by — a fellowship in South Africa, years of work as a speechwriter, a return to Harvard to study law, a congressional campaign in my old home state of Illinois, and finally a career as a journalist with Andrew Breitbart.

I continued my interest in creative writing, both in fiction and non-fiction, and about a decade ago I decided to write an ebook (now on audio) about the Biblical Book of Kings. The Book of Kings (I and II) describes the fall of the ancient Jewish monarchy, from the height of ancient Israel at the end of King David’s reign to the destruction of the Holy Temple and the exile of the Jewish people, generations later. I sensed that there were political lessons — warnings — for America.

It turns out that some of the most interesting commentaries on the Book of Kings are written by Christian scholars, who have long been drawn to the political implications of the text. I also approached rabbis and scholars for some advice about which Jewish sources to consider, and they pointed me in the direction of Yalkut Me’am Lo’ez, a series originally written in Ladino, a language spoken by Spanish Jews that is similar to Spanish but written in Hebrew characters.

Me’am Lo’ez has an extensive and insightful commentary on the Book of Kings. Throughout, however, it refers to an earlier text: a tractate in the Babylonian Talmud called Sanhedrin, which deals with the system of religious courts. Like much of the Talmud, the text of Sanhedrin digresses into discussions on a wide variety of topics, including — in this case — the Book of Kings, which is discussed in depth across about a dozen pages. So I bought my first and only Talmud volumes — all published by ArtScroll, which features the Hebrew and Aramaic text alongside an English translation.

I consulted Sanhedrin (which takes up three volumes) in writing my ebook, and that was it. But one day, when my family and I were spending the weekend with friends, another guest came down to breakfast with a volume of Talmud.

He seemed familiar: I recognized him as a classmate from the yeshiva in Jerusalem, nearly twenty years before. He said he was trying to pick up his religious studies again, and had joined a daily Talmud study program known as Daf Yomi.

The Daf Yomi program was inaugurated in 1923 by Rabbi Meir Shapiro in Poland, and has since been taken up by Jews around the world. But even though I had attended one or two Daf Yomi classes, I had never attempted to join.

I looked at my friend’s volume of Talmud: it was Sanhedrin. And lo and behold, the daily lesson for that particular Saturday morning happened to be one of the few pages in Sanhedrin I had actually studied, about the Book of Kings.

I decided that this could not have been a coincidence.

I returned home and began studying Sanhedrin, completing several pages a day until I had caught up to the Daf Yomi schedule. About a year later, another friend from my synagogue who had started the Daf Yomi program introduced me to the daily online lectures by Rabbi Eli Stefansky, who teaches in both English and Hebrew from his beit midrash (study hall) in the Israeli city of Beit Shemesh.

I was hooked. The monumental task of studying the Talmud, in which every page is accompanied by an incredibly detailed set of commentaries, suddenly seemed possible. The Daf Yomi program moves at a pace too rapid for intense study, but it makes the Talmud accessible.

Seven years is a long time — but a day is short, and I had already learned from my experience of writing books that you can achieve almost anything if you break it down into small tasks.

Studying the Talmud did not make me a rabbinical scholar. I would be hard-pressed to recall from memory much of what I learned over the past seven years (though I started taking notes in the third year, and refer back to those often).

Some of the Talmud is as tedious and legalistic as I remembered from yeshiva. Yet there are also incredible pearls of wisdom, insights into the Bible, entertaining stories about Jewish Sages, and pieces of advice for everyday happiness.

For example, in a passage I recently studied in the tractate of Bava Batra, which deals with financial law, the Talmud stresses the importance of maintaining accurate weights and measures. If anything, it says, merchants should tilt their scales by one unit in favor of their customers, to remove any possibility that people will suspect impropriety. Here we have an early example of the principle that “the customer is always right,” which is good for all involved.

For centuries, antisemites have long tried to use the Talmud to slander Jews. Typically, they cherry-pick controversial passages, or simply make up claims about what is in the text, taking advantage of the fact that the compendium is so long that few will bother to challenge their claims. Recently, I felt fortunate that I could use my knowledge of Talmud to respond to one such attack.

Seven years have flown by — two presidential elections, the pandemic, a new home, two more children — and yet as I opened the first page of Sanhedrin this week, beginning again where I had left off, it seemed no time had passed at all.

The dialogue between the rabbis of the Talmud — who recorded every dissenting opinion — is as fresh today as it was thousands of years ago. And I am grateful for the chance encounter with an old friend that set me on my journey.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News and the host of Breitbart News Sunday on Sirius XM Patriot on Sunday evenings from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. ET (4 p.m. to 7 p.m. PT). He is the author of The Agenda: What Trump Should Do in His First 100 Days, available for pre-order on Amazon. He is also the author of The Trumpian Virtues: The Lessons and Legacy of Donald Trump’s Presidency, now available on Audible. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.