Prices Rise, Homes Sell Swiftly, But the Market Feels Lousy

What if we had a housing recovery and no one showed up?

We have been exploring the end of the recession in the housing sector and the nascent recovery for months here in the Breitbart Business Digest. Yet for a lot of people, the housing market still feels pretty lousy because so many cannot participate in the recovery.

The July sales figures released Tuesday by the National Association of Realtors provide more evidence that the housing recession is over and the recovery has begun. The median price of an existing home sold rose for the first time in several months, 35 percent of homes were sold above their asking prices, and 74 percent of homes were on the market for less than a month before they were sold. Ordinarily, this would look and feel like a great market.

But it sure does not feel like a great market right now.

Haunted by the Ghosts of Mortgage Rates Past

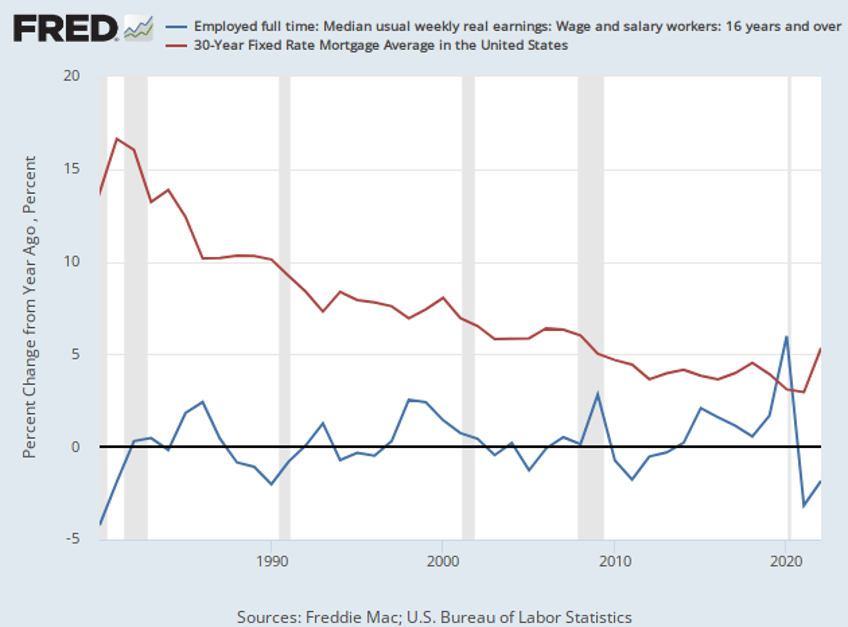

The trouble is not just that mortgage rates are so high. They’ve been higher before, as anyone who bought a home before the turn of the century will remind you if they hear you complaining about seven percent plus rates on the 30-year. However, back in the 1980s and 1990s, average inflation-adjusted weekly wages tended to rise, giving homeowners more financial strength to handle the heavier mortgage. But over the last two years, real wages have fallen.

It’s also not just that prices are high. High prices hurt affordability for first-time buyers, especially when interest rates are high, but homeowners moving into their second home are not hurt as much since they also tend to be sellers of an appreciated home. Indeed, existing homeowners often feel good about a rising market because the asset they own is becoming more valuable—even if it means their aspirational home is also becoming more expensive.

Which is not to say that high prices are not playing a role in making the recovery feel like a prolonged recession. Since the turn of the century, home prices are up by around 180 percent, and wages are up around 100 percent, according to Lawrence Yun, the chief economist of the National Association of Realtors. Since the housing bust that preceded the Great Recession, the U.S. has not been building enough houses to keep up with demand, keeping the total supply of houses low and pushing up prices.

A construction worker works on a townhome in Plano, Texas, on May 16, 2012. (AP Photo/Tony Gutierrez)

Perhaps the most important obstacle facing the housing market today is not that prices are high and rates are high but that rates have been so low. From 2010 through 2020, the average new 30-year mortgage had a mortgage rate of less than 3.92 percent. There were four years in that period in which the average was less than 3.75 percent. A great many mortgages were refinanced at those low rates, and many homes were purchased with low rates. Freddie Mac’s quarterly reporting shows that as of the first quarter of this year, more than sixty percent of mortgages had rates lower than four percent at their origination.

Locked-In and Fed Up

This huge legacy stock of low interest mortgages means that many people find selling their homes unaffordable—even if their current home has appreciated. An older couple looking to sell their “empty nest” for a condo in Florida, for example, might easily discover that “downsizing” into a smaller home would trigger an unsustainable rise in their monthly living expense. Many younger families who might otherwise look to buy a bigger home are likely to opt for home improvement rather than trading from a three percent mortgage to a 7.5 percent mortgage.

This “lock-in” effect from low interest legacy mortgages is the primary reason home sales are so low. In July, they were expected to hold up with the June rate. Instead, they fell 2.2 percent. Single-family home sales fell 1.9 percent, the fifth consecutive month of declining sales. On a year-over-year basis, overall home sales were down 16.6 percent. The 3-month average of existing home sales declined to 4.18 million, down from 4.42 million as of April.

The number of homes for sale rose from a month earlier to 1.11 million, but this is still the smallest July inventory—normally a big month for sales—since 1999. Single-family homes for sale are near their lowest level since the 1980s.

This suspended animation housing market will likely have broader economic consequences. By raising the cost of moving for a new job, it is likely to contribute to a less liquid market in labor and inefficient geographical distribution of labor. The immobility introduces frictions into the economy, preventing workers from going where there is the most demand. This can slow economic growth.

Similarly, it can contribute to inflation. The lack of inventory will encourage the owners of rental properties to raise rents—as will the renewed climb in home prices. This will drive up inflation on its own. But there’s also the wage-inflating effects created by the mortgage lock-in. In order to entice workers to move for jobs, employers will have to offer higher wages to compensate for increased mortgage costs.

(iStock/Getty Images)

Perhaps the least noticed challenge created by the legacy low rates is that they will likely make it harder to stimulate the economy in a future downturn. Ordinarily, when the Fed cuts its interest rate target, this very quickly filters through to the mortgage market, which in turn stimulates home buying, selling, and building. The housing sector is typically regarded as one of the most direct channels through which monetary policy acts on the economy. The economy also gets a boost from refinancing, as homeowners take out new loans on their homes and spend down their equity.

The next time the Fed cuts rates, however, it may have to cut deeper in order to juice home sales. Many homeowners will not necessarily be tempted to sell because even with a lower mortgage rate than the current one, they’ll still be facing rates higher than their legacy mortgage. Refinancings will be even harder to ignite, which means the stimulus from the extra spending that they normally engender will be sparse.

The ultra-low interest rate policies adopted in the wake of the Great Recession and to fight off the pandemic downturn were never going to be costless. We’re only now finding out just how high a tab we have rung up.