The Lamp of Experience Sheds Light on Tariffs

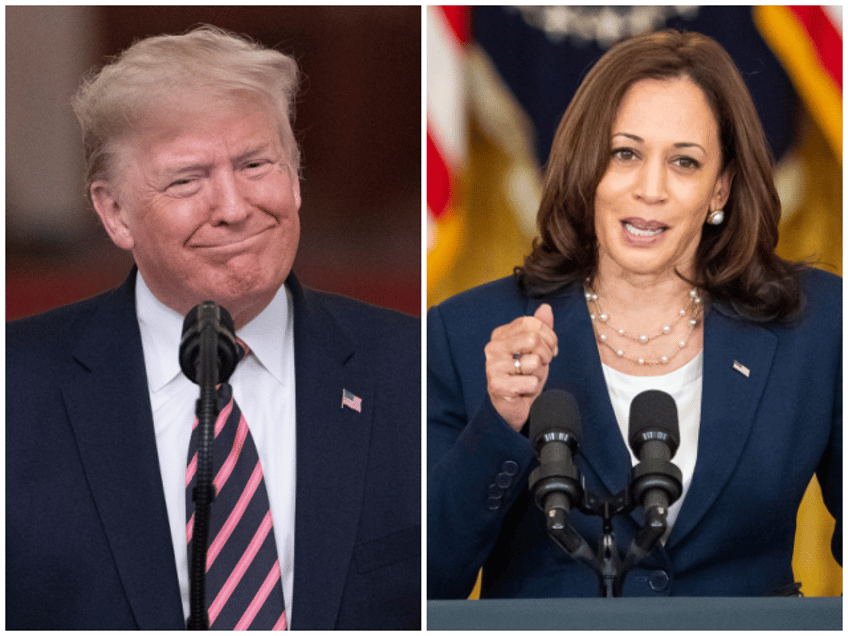

Donald Trump will have a powerful tool at his disposal in his debate with Kamala Harris this week: the lamp of experience.

When Trump came into office on a promise of tearing up international agreements and imposing tariffs, many of his critics were quick to claim the president was starting a trade war. Establishment economic forecasters on the left and right confidently predicted that Trump’s tariffs would hurt the U.S. economy and raise consumer prices.

Eight years ago, these claims were at least plausible on their face. It had been generations since the U.S. had invoked a muscular trade strategy that included broad tariffs rather than just piecemeal tariffs on products that were illegally being dumped into U.S. markets. The anti-tariff crowd did not have much evidence to support their claims, but it had been so long since we had used trade tariffs strategically that there was not all that much direct evidence on the other pro-tariff side either.

What Trump had on his side was economic theory. You would not know it from the way many economists talk about tariffs, but standard economic theory supports Trump’s claim that tariffs are often paid for by the country whose exports are subject to the increased duties and not by the country importing the goods. Trade theory has long found that tariffs applied by a large economy such as the U.S. tend to drive down foreign prices, as exporting nations have no other choice to offload their excess production.

In fact, it’s long been known to economists that imposing a tariff can improve the terms of trade so much that domestic prices of imported goods subject to the tariff actually fall. This is known as the Metzler Paradox after economist Lloyd Metzler who first wrote about the idea all the way back in 1949. What’s more, by increasing the incentives to invest in domestic production, the tariffs can increase global output of the tariffed goods, which also puts downward pressure on prices.

Price theory also tells us that tariffs are unlikely to raise consumer prices. Although many people imagine that the prices they pay at the cash register are an accumulation of the costs of their inputs, the reality is pretty much the opposite. Consumer demand determines the price of the final product, which then determines the prices of the components and labor that go into making the product. So, when a tariff raises the cost of imports, in a competitive economy there’s no real way for merchants to pass on the cost.

If that’s what economics teaches, why did so many economists claim that tariffs would raise prices? Two big reasons are politics and social status. Like a huge swathe of our professional and academic classes, economists are overwhelmingly to the left of Donald Trump. And they value their prestige among their peers, which requires criticizing Trump. So, they tend to object more loudly to his policies than is warranted. Notice, for example, how much less caterwauling there has been about the tariffs since Joe Biden became president and kept many of them in place. The tariffs were bad because they were Trump’s tariffs.

A third reason is that a lot of economists were using an outdated mental model of Trump’s tariffs. If a tariff is imposed to protect a domestic monopolists market share, it is likely to mean prices will be higher than they otherwise would have been. But Trump’s tariffs were not “protectionist” in that sense at all. They were aimed at achieving more favorable terms of trade for the U.S., and the U.S. market they sought to “protect” against the mercantilism of China is a competitive one rather than one dominated by monopolistic manufacturers.

The Record Is Clear: Tariffs Don’t Raise Consumer Prices

The record is now clear that the tariffs’ opponents were wrong when they said consumers would face higher prices. The prices of durable goods in the U.S. fell by 2.1 percent from the start of Trump’s presidency to the beginning of the pandemic in January 2020. If we include the pandemic and the run-up in goods prices that followed, the price of durable goods rose 1.3 percent. That’s not an annual rate of inflation. That’s 1.3 percent over four years.

Here’s how the Washington Post reported the effects of tariffs in 2020, when they finally admitted the tariffmeggedon narrative was wrong:

Headlines last year proclaimed Trump’s tariffs could cost the typical American family $1,000 more a year. The eye-popping number came from a JPMorgan analysis that assumed the full cost of the tariffs would be passed on to consumers, which is what is generally taught in introductory economics classes.

But that is not what’s been happening. The evidence so far indicates that most American firms passed only a fraction of the cost increase on to consumers — more in the range of $100 per family a year…

But a recent study by economists at Harvard University, the University of Chicago and the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston went a step further, examining data from two large retailers on prices of similar goods, some of which face tariffs and some that do not. The economists found a “quite modest” price difference, suggesting that U.S. companies and retailers are eating a lot of the costs and making lower profits.

The price hike for affected dishes, furniture, linens, toaster ovens, towels and umbrellas was less than 1 percent, the study found. And the price for electronics only went up by 1.4 percent.

Almost all of the studies that have looked at tariffs have found that there was very little pass-through to retail prices paid by U.S. households. Instead, the studies have found that some of the tariffs imposed by Trump—especially on metals—were absorbed by exporting nations. Others were paid by importers but not passed on to consumers. No major study of the broad Trump China tariffs has found evidence of a sizable pass-through to consumers. Even the studies that claim that tariffs were paid for by Americans and not China only show that they were paid for by the corporate sector rather than the household sector.

When Harris or the debate moderators claim further tariffs will be a tax on consumers, Trump can point to his first term to show that no such thing occurred. And in relying on experience rather than rhetoric, he will be echoing American founding father Patrick Henry.

“I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided, and that is the lamp of experience. I know of no way of judging the future but by the past,” Henry said in 1775.