The Dirty Secret of Economics: Trump Is Right on Trade

One of the least discussed but most obvious realities of modern trade is that Donald Trump is, in his rough-hewn way, mostly right about tariffs, while the accepted wisdom mouthed by the media, think tanks, and economists for public consumption is, if not wrong, at least incomplete.

Trump’s basic argument is straightforward: U.S. trade policy has been naïvely generous, flinging our markets wide open while tolerating a laundry list of barriers from our so-called partners. The result, he claims, has been a direct hit to American prosperity. His prescription? A more balanced trade approach—one that demands reciprocity and uses leverage to pry open foreign markets.

Now, if that sounds like a fairly sensible proposition, you might be wondering why this draws such ire from the intellectual halls of economics. After all, economists love free trade and preach that more of it makes everyone richer. Specialization, comparative advantage, and all that. And yet, here’s the rub: when Trump talks about using tariffs to get to that promised land of freer trade, they balk.

The fact is, economists are in a bit of a pickle here. On one hand, they should theoretically applaud a strategy aimed at reducing global barriers to U.S. goods—something that’s long been part of their playbook. On the other hand, the mere whiff of association with Trump is enough to make most of them retreat into silence. Academia and professional circles can be unforgiving places for anyone caught publicly agreeing with Trump.

Raising Tariffs Doesn’t Lead to Trade Wars

What really sticks in their craws, though, isn’t Trump’s goal but his method. Tariffs, economists claim, are dangerous tools, sure to provoke retaliation and tip us all into a damaging trade war. The political forecast is grim: we raise tariffs, they raise tariffs, and global trade goes into a downward spiral.

But here’s where things get interesting. Economic theory itself doesn’t back this up as clearly as some might think. Economists often argue that the burden of a tariff falls on domestic consumers. If that’s true, then retaliatory tariffs should be irrational, as they would primarily harm the retaliating nation. In fact, if countries were behaving according to strict economic theory, they’d have little reason to retaliate at all—unless, of course, the real drivers are political. Pride, special interests, and national posturing may well explain the expected retaliation better than any economic model.

There’s also a less-talked-about possibility: perhaps trade barriers aren’t quite the deadweight cost they’ve been made out to be. Some research even suggests that under certain conditions, countries can raise barriers without suffering the predicted economic hit. Maybe that’s why some of our trade partners hold on so tightly to their own barriers. A well-crafted tariff can redistribute wealth from trading partners or even create a near-monopoly on key products, allowing countries to capture the benefits of economies of scale.

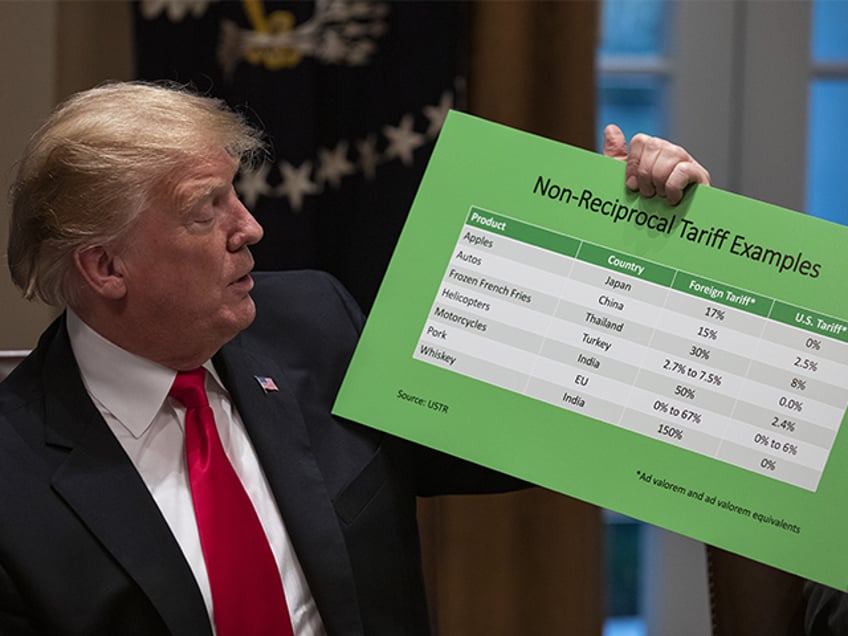

President Donald Trump speaks while holding a chart illustrating non-reciprocal tariff examples during a meeting in the Cabinet Room of the White House on January 24, 2019. (Alex Edelman/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

A good deal of the literature on trade theory actually supports this idea, arguing that if a country can get away with raising barriers without retaliation, it can redistribute wealth from its partners to itself. Similarly, if a country uses trade barriers to erect what amounts to a global monopoly in certain goods, it can achieve wealth-enhancing economies of scale in the production of those products. In that case, countries might be reluctant to surrender their wealth enhancing trade barriers and might even double down in the hopes that the U.S. will back off.

If that’s right, however, it’s really a matter of the U.S. credibly establishing that it will no longer tolerate unbalanced trade that has allowed a wealth transfer from the U.S. to our trading partners. That likely will require raising tariffs, to show we are not bluffing, and perhaps raising them again in response to any initial retaliation, to show we will not back down. Once convinced that the game of taking advantage of the U.S. is over, trading partners should be expected to reduce their own barriers.

So, when economists predict retaliation, they’re not really relying on economic principles—they’re predicting political moves. What Trump understood, perhaps instinctively, is that getting the U.S. out of its long-standing trade trap would require taking a tough stand—raising tariffs, showing that we’re serious, and even escalating if necessary. Our trade partners will only consider dropping their barriers when they believe that the days of taking advantage of the U.S. are over.

And here’s the kicker: the numbers support Trump’s approach. According to the Penn Wharton Budget Model, if the U.S. raises tariffs and our trading partners reduce theirs in response, the U.S. economy could be 1.3 percent larger in 20 years than it would be if we kept the status quo. If Trump’s tariff strategy is successful enough to bring down all trade barriers, we’re looking at an economy eight percent larger over the same period, according to the model.

In a political landscape where big promises often fizzle, Trump’s trade policies might just hold out the possibility of real tangible growth. The question now is whether we, as a country, have the nerve to push through the noise and give this strategy a real shot.