Can the Fed Read the Room?

The economy is signaling that it does not need a rate cut to keep growing. The question is whether the Federal Reserve is listening.

The S&P Global Flash U.S. Composite PMI rose to a seven-month high in January, indicating accelerating economic growth as we forge ahead into 2024. The reading of 52.9 beat all estimates.

The manufacturing purchasing managers index (PMI) jumped to a 15-month high of 50.3, suggesting that the sector may be recovering after a dismal year. The services index rose to 52.9, a seven-month high.

New business expanded for the third consecutive month and new orders at manufacturers rose for the first time since October 2023. This was the fastest uptick in orders for manufacturers since May of 2022. The economy, in other words, appears to be setting off to once again surprise analysts to the upside.

“An encouraging start to the year is indicated for the US economy by the flash PMI data, with companies reporting a marked acceleration of growth alongside a sharp cooling of inflation pressure,” Chris Williamson, chief business economist at S&P Global Market Intelligence, said.

While this is an “encouraging” start in terms of growth, it severely undermines the case for a rate cut early this year. Recall that Fed officials have said a number of times that growth will need to slow to “below trend”—which the Fed considers a 1.8 percent annual pace—to achieve a lasting return to inflation at its two percent target.

“Forecasters generally expect gross domestic product to come in very strong for the third quarter before cooling off in the fourth quarter and next year. Still, the record suggests that a sustainable return to our 2 percent inflation goal is likely to require a period of below-trend growth and some further softening in labor market conditions,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said back in October.

The economy has certainly slowed down from the breakneck pace of 4.9 percent in the third quarter. But it very likely has not slowed down enough to qualify as below trend. Wall Street is expecting the Bureau of Economic Analysis to report that gross domestic product expanded two percent in the fourth quarter, and the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow measure estimates 2.4 percent.

Some of those pushing for the Fed to cut rates early this year argue that the Fed should do so to avoid an “unnecessary recession.“ The argument is that because inflation has come down so much without an economic slowdown or much damage to the labor market, the Fed can afford to cut rates to avoid a significant economic downturn.

This is not wholly without merit. As inflation falls, the real fed funds rate rises. When personal consumption expenditure inflation was at seven percent, a 5.4 percent fed fund rate was still negative in real terms. Now that inflation is at 2.6 percent, the same real fed funds is positive and—in theory—restrictive.

The trouble is that the economy is showing it can more than tolerate the current real rate. What’s more, longer term real rates have fallen significantly. Back in October, the real 10-year yield—the 10-year yield minus the PCE inflation—was two percent. Today it is 1.5 percent. There’s plenty of room for argument about how to measure real rates—whether to use actual current inflation or some measure of expected inflation—but its very clear real rates have fallen over the past few months.

In an economy that is accelerating with real rates falling, a Fed cut risks reigniting inflation.

The Era of Goods Disinflation Is Over

As Williamson said, inflationary pressures did cool in January, but the cooling was uneven. Input prices rose at a slower pace for service providers, and the services sector reported the slowest rise in output charges since the current wave of inflation began in June 2020.

Manufacturers, however, managed the steepest rise in their output prices since April 2023. They also saw a sharper uptick in costs. Manufacturers also mentioned that output was being stymied by severe storms and shipping disruptions. Supplier delivery times lengthened on average for the first time in 13 months.

Those supply chain problems may get worse as the Red Sea conflict drags on and global shipping becomes more congested. Even goods that never were going to pass through the Red Sea can be affected by the fact that it now takes 20 percent more time to ship goods between Europe and Asia. That leaves the world with less available shipping capacity, which will raise shipping prices, delay deliveries, and potentially cause shortages and manufacturing disruptions.

A cargo ship transits the Suez Canal towards the Red Sea on January 10, 2024, in Ismailia, Egypt. (Sayed Hassan/Getty Images)

So, although inflationary pressures may have cooled in January overall—as they were widely expected to—the cooling may not last. Businesses and financial markets were anticipating that disinflationary pressures from goods would run out of steam early this year but not that the goods sector would start to contribute to inflationary pressures.

The Worst Outcome Is a Cut and Reverse

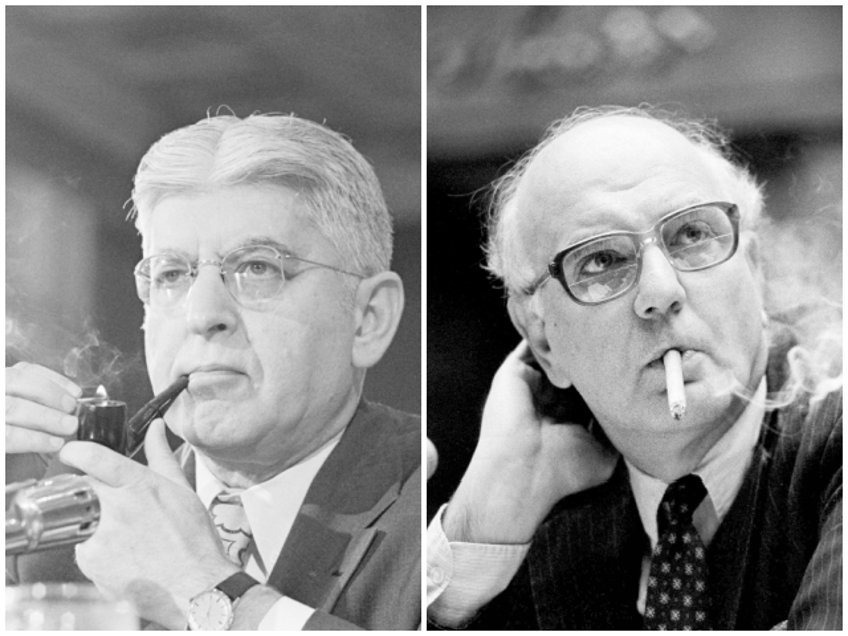

Powell has repeatedly argued that the stop and start monetary policy of the Arthur Burns-led Fed in the 1970s badly undermined the central bank’s credibility on inflation and resulted in inflation becoming entrenched at a higher level, triggering the era of stagflation. Even legendary inflation fighter Paul Volcker eased too early and had to tighten again, leading to a much worse recession.

Former Federal Reserve Chairmen Arthur Burns (left) and Paul Volcker. (Getty Images; John Duricka/AP Photo)

The lesson of the the eventual success of Volcker is that the Fed needs to “keep at it until the job is done,” Powell has told us.

This was echoed recently by Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic and Fed Governor Chris Waller.

“We do not want to go on these up-and-down or back-and-forth patterns,” Bostic said on January 18.

“The worst thing we’d have is that it all reverses and we’ve already started to cut,” Waller said in an interview with the Brookings Institution.

Given the evidence of acceleration in the economy in December and January, a Fed averse to repeating the mistakes of the past is likely to keep rates on hold.