New Year, Slightly More Sober Markets

The market appears to be losing a bit of its nerve when it comes to the conviction that the Federal Reserve will aggressively cut rates this year.

The early rate cut thesis began to take hold of the imagination of traders in the fourth quarter of last year as it became clear that the Fed’s July rate increase was the final hike of 2023. Historically, the average time between the last Fed hike and the first cut is eight months, putting the Fed’s March meeting definitely within the range of plausibility.

Following the Fed’s December meeting and Fed Chief Jerome Powell’s decidedly dovish press conference, the market decided that a March cut was all but inevitable. As of last week, the fed funds futures market was indicating a 90 percent chance of at least one cut by the March meeting, including a 17 percent chance of two quarter point rate cuts or a single fifty basis point cut.

This was good for bond prices and stock prices, triggering a Santa Claus rally in both. Bonds were bid up, pushing the yield on the 1o-year below the four percent level that had been seen as a fanciful forecast by Wall Street’s extreme doves just a few months earlier. Stock prices leapt like a stag across a frosty brook.

A bit of sobriety has crept into the market in the New Year. The odds of a March cut implied by the fed funds market are still very high, but they have fallen to around 75 percent. The yield on the 10-year has been flirting with crossing above the four percent threshold. The major stock indexes were headed down for a second consecutive day on Wednesday.

Looking further out into the year, the implied forecast for the fed funds rate at the end of year has shifted. The odds still favor a Fed target range of 3.75 to four percent, which is one and a half points lower than the target in place since July. That’s a forecast of six quarter-point cuts this year, around twice the median projection of Fed officials in the December summary.

But the odds of just 1.25 percent points of cuts have roughly doubled to nearly 23 percent, while the odds of 1.75 percentage points of cuts have fallen from 39 percent to 28 percent. In other words, there’s a lot less certainty implied by futures prices than there was on the other side of the new year.

The Risk of Reacceleration Is Rising

The market is still underpricing the risk that the economy accelerates enough to reignite inflation or at least push Fed officials to hold off on cutting rates.

The housing market, for example, is not cooperating with the idea that inflation will continue to fall next year. The Case-Shiller national home price index rose for the ninth consecutive month in October, indicating that home prices are up 4.8 percent from a year ago. Just counting 2023, home prices were up 6.3 percent through October. These prices tend to be a leading indicator for the housing components of inflation—rent and the owners’ equivalent of rent—so we should expect the large housing component of the consumer price index to start exerting an upward pull later this year.

We learned on Tuesday that construction spending was up in November, the eleventh month of increases. For the year, construction spending is up 11.3 percent. Private residential construction rose 1.1 percent in November, with single-family construction rising 2.9 percent. This is a sign that financial conditions are loosening in one of the most interest rate sensitive sectors of the economy.

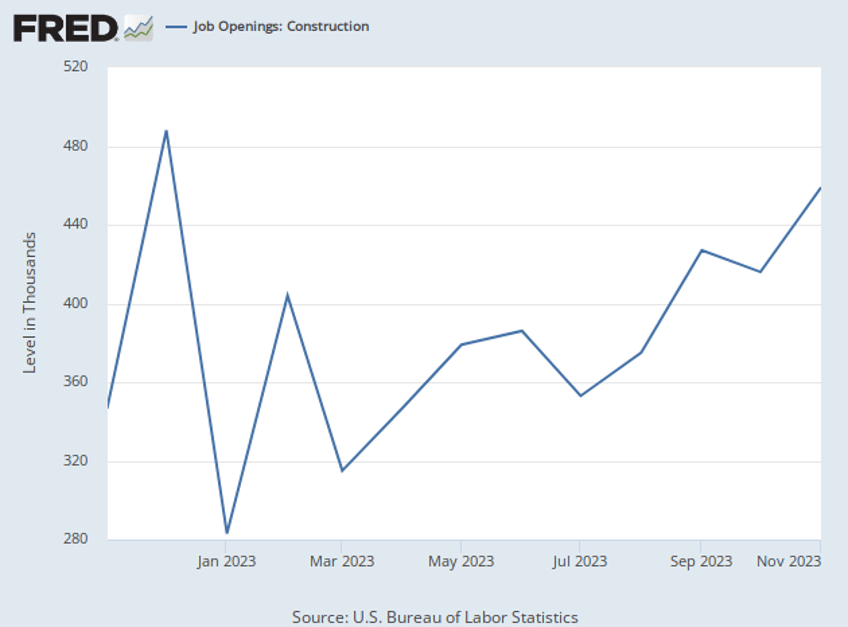

The release of the November Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, appeared to provide reassurance that the labor market is cooling, with openings falling and coming in slightly below expectations. But progress on openings appears to have slowed in recent months. What’s more, openings are rising quickly in construction and are closing in on their post-pandemic high. Openings in durable goods manufacturing, another interest rate sensitive sector, rose for the second consecutive month.

We began last year with the market convinced that the economy would fall into a recession, forcing the Fed to cut rates. We begin this year with the market still convinced that the Fed will cut rates, although the fear of a recession has been vanquished. The risk, however, is the same: an accelerating economy could force the Fed to keep rates higher than the market foresees.