Financial advisors get a bad rap. Some deserve it; most don’t. The problem for the entire investment advisory and portfolio management community stems from the “career risk” they inevitably face. That “career risk” has been exacerbated over the last decade as massive monetary interventions and zero interest rates created outsized returns. A point we discussed last week in “A Permanent Shift Higher In Valuations.”

“The chart below shows the average annual inflation-adjusted total returns (dividends included) since 1928. I used the total return data from Aswath Damodaran, a Stern School of Business professor at New York University. The chart shows that from 1928 to 2021, the market returned 8.48% after inflation. However, notice that after the financial crisis in 2008, returns jumped by an average of four percentage points for the various periods.”

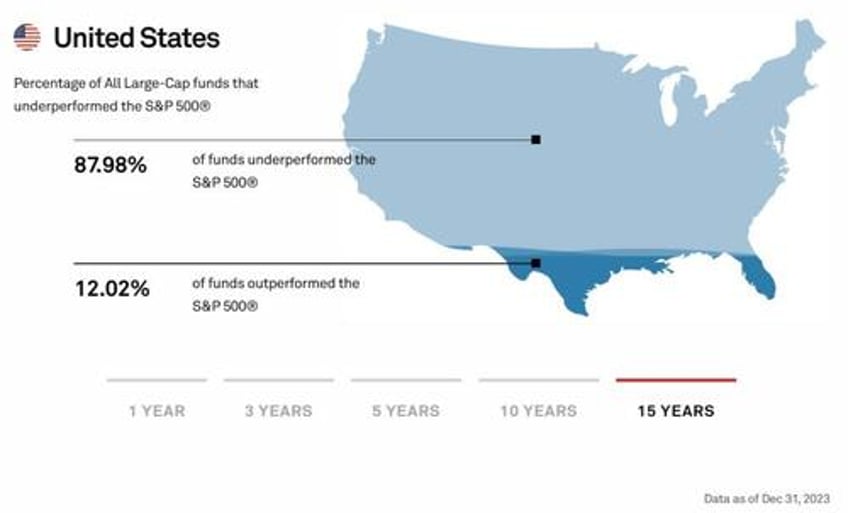

With social and mainstream media reporting on the latest investment hype surrounding market phases like “disruptive technology,” “meme stocks,” and “artificial intelligence,” it is unsurprising investors will salivate over the next “get rich quick” scheme. In addition, the annual reports from SPIVA measuring the performance of actively managed funds against their benchmark index intensify the “fear of missing out.”

The SPIVA report further fuels the debate over active versus passive indexing, or the “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em” mentality.

Unsurprisingly, the result is the increasing pressure on financial advisors and portfolio managers to “chase performance.” Such is the basis of “career risk.”

“Career risk is the probability of a negative outcome in your career due to action or inaction.”

In other words, if financial advisors or portfolio managers don’t meet or beat benchmark returns from one year to the next, they risk losing clients. Lose enough clients, and your “career” is over. However, it is worse than that because even if the client states they are “conservative” and want little risk, they then compare their returns to that of an all-equity benchmark index. (Read this to understand why benchmarking your portfolio increases risk.)

Therefore, this career risk forces financial advisors and portfolio managers to push boundaries due to the risk of losing clients.

That brings us to two primary questions. The first is how we got here. The second is what you (as an investor or financial advisor) should do about it.

Performance Chases Performance

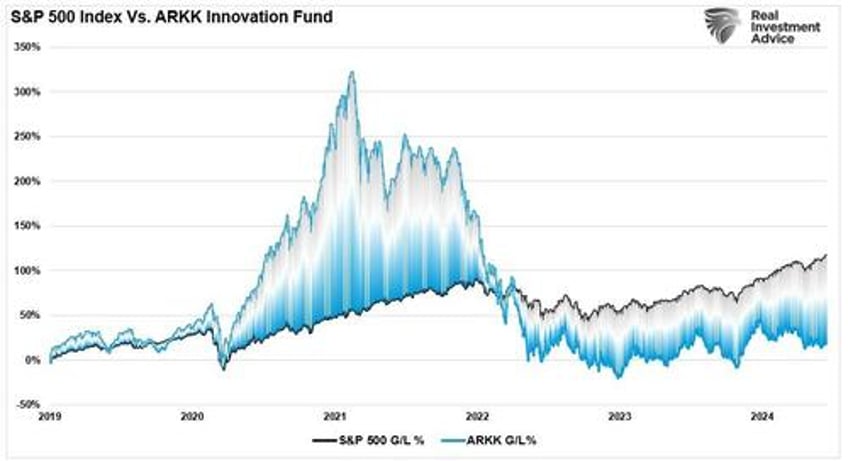

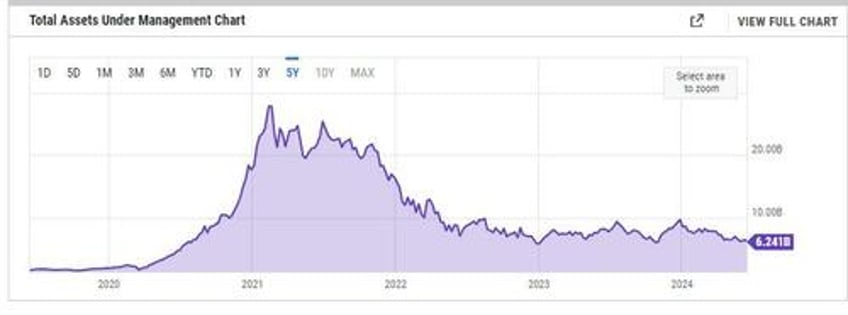

I recently discussed on the “Real Investment Show” that there is a big difference between a financial advisor or portfolio manager and an individual investor. The difference is the “career risk” of underperformance from one year to the next. Therefore, advisors and managers MUST own the assets that are rising in the market or risk losing assets. A great example of career risk is seen with Cathy Wood’s ARK Innovation Fund. That fund was the darling of Wall Street during the “disruptive technology” mania phase of the market following the stimulus-fueled investing craze following the Pandemic shutdown.

Unsurprisingly, during the mania phase, investors poured billions into the fund. Unfortunately, as with all mania phases, that investing style lost favor, and the fund has recently underperformed the S&P 500. That underperformance resulted in a massive loss of assets under management for ARK and Cathy Woods

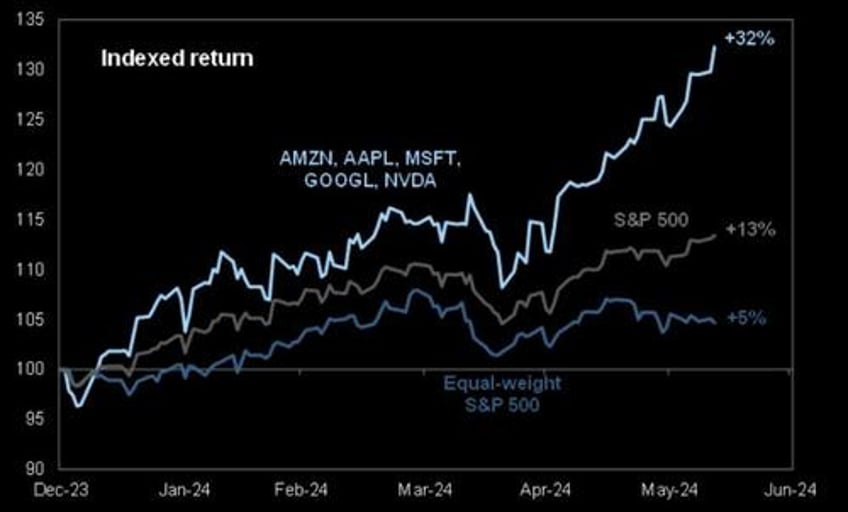

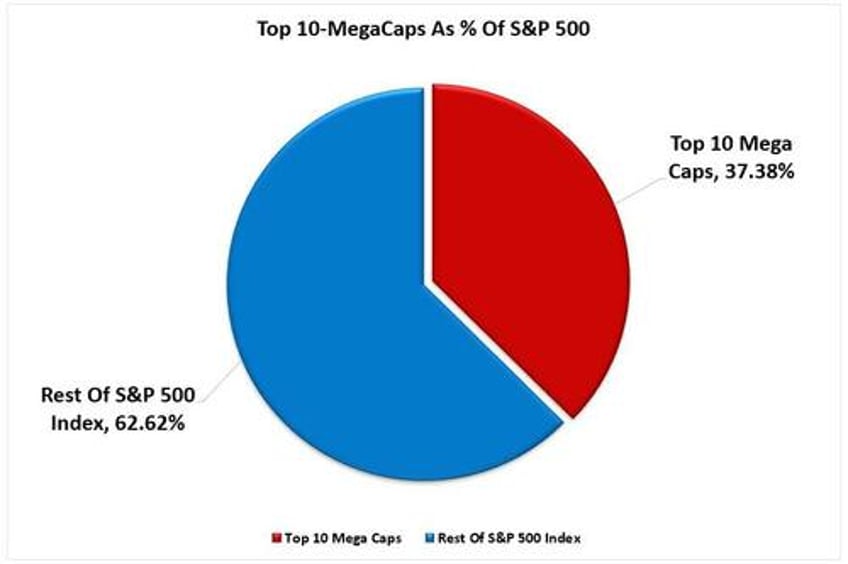

Today, the investment chase is all about “artificial intelligence.” Such has led to an enormous bifurcation in the market as a handful of stocks increasingly rise versus the rest of the market, as shown.

Once again, portfolio managers and financial advisors face enormous “career risk” pressure. As discussed in “It’s Not 2000,” as the market’s breadth narrows, advisors and managers must take on increasingly larger weights of fewer stocks in portfolios.

“The top-10 stocks in the S&P 500 index comprise more than 1/3rd of the index. In other words, a 1% gain in the top-10 stocks is the same as a 1% gain in the bottom 90%. As investors buy shares of a passive ETF, the shares of all the underlying companies must get purchased. Given the massive inflows into ETFs over the last year and subsequent inflows into the top-10 stocks, the mirage of market stability is not surprising.

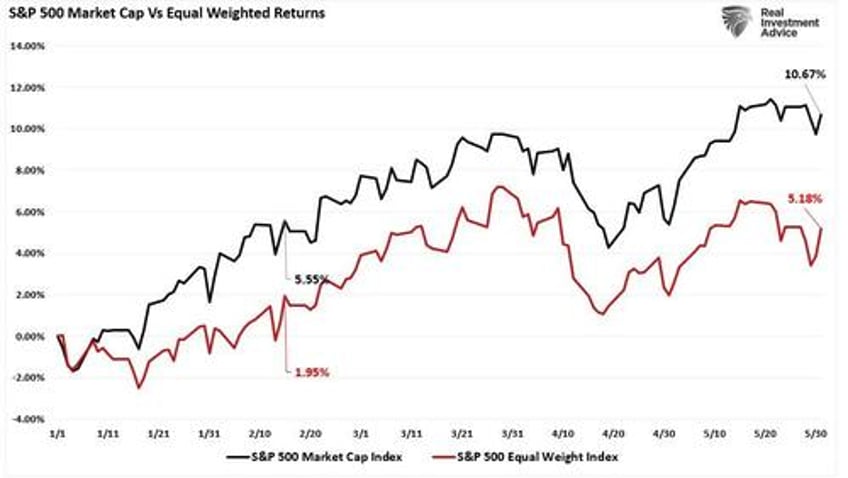

“That lack of breadth is far more apparent when comparing the market-capitalization-weighted index to the equal-weighted index.”

The question every investor should be asking themselves is:

“Is it really wise from risk management perspective to have nearly 40% of my portfolio in just 10-stocks?”

However, if you answer that question “no,” or if you have any other type of investment allocation, you will underperform the benchmark index. If you have an advisor or manager that matches a portfolio to your financial goals, they will also underperform. They now face the potential “career risk” of getting fired if the client fails to understand the reason for the underperformance.

So, what should financial advisors and clients do?

What Should Advisors Do?

For advisors, “career risk” is a real and present danger. Many opt for simplistic ETFs or mutual fund-based portfolios that track an index. The question is, as a client, what are you paying for?

Knowing that clients are emotional and subject to market volatility, Dalbar suggests four practices to reduce harmful behaviors:

Set Expectations Below Market Indices:

Set reasonable expectations and do not permit expectations to be inferred from historical records, market indexes, personal experiences, or media coverage. The average investor cannot be above average. Investors should understand this fact and not judge the performance of their portfolio based on broad market indices.Control Exposure to Risk:

Explicit, reasonable expectations should be set by agreeing on predetermined risk and expected return. Focusing on the goal and the probability of its success will divert attention away from frequent fluctuations that lead to imprudent actions.Monitor Risk Tolerance:

Even when presented as alternatives, investors intuitively seek capital preservation and appreciation. Risk tolerance is the proper alignment of an investor’s need for preservation and desire for capital appreciation. The determination of risk tolerance is highly complex and is not rational, homogenous, or stable.Present forecasts in terms of probabilities:

Provide credible information by specifying probabilities or ranges that create the necessary sense of caution without adverse effects. Measuring progress based on a statistical probability enables the investor to make a rational choice among investments based on the reward probability.

When Must Advisors Take Action?

Dalbar’s data shows that the “cycle of loss” starts when investors abandon their investments, followed by remorse as the markets recover (sell low). Unsurprisingly, the investor eventually re-enters the market when their confidence gets restored (buys high).

Preventing this cycle requires having a plan in place beforehand.

When markets decline, investors become fearful of total loss. Those fears compound as the barrage of media outlets “fan the flames” of those fears. Advisors must remain aware of client’s emotional behaviors and substantially reduce portfolio risk during major impact events while repeatedly delivering counter-messaging to keep clients focused on long-term strategies.

Dalbar notes that during impact events, messages delivered to clients should have three characteristics to be effective at calming emotional panic:

Deliver messages when fear is present. Statements made well before the investor experiences the event will not be effective. On the other hand, if the messages are delivered too long after the fact, investors will already have made decisions and taken actions that are difficult to reverse.

Messages must relate directly to the event causing the fear. Providing generic messages such as the market has its ups and downs is of little use during a time of anxiety.

Messages must assure recovery. Qualified statements regarding recovery tend to fuel fear instead of calming it.

Messages must ALSO present evidence that forms the basis for forecasting recovery. Credible and quotable data, analysis, and historical evidence can provide an answer to the investor when the pressure mounts to “just do something.”

Providing “generic media commentary” with a litany of qualifiers to specific questions will likely fail to calm their fears.

Conclusion

An experienced advisor does more than “invest money in the market.” The professionals’ primary job is providing counsel, planning, and stewardship of the client’s financial capital. In addition, the advisor’s job is to understand how individuals respond to impact events and get in front of them to plan, prepare, and initiate an appropriate response.

Negative behaviors all have one trait in common. They lead individuals to deviate from a sound investment strategy tailored to their goals, risk tolerance, and time horizon. The best way to ward off the aforementioned negative behaviors is to employ an approach that focuses on one’s goals and is not reactive to short-term market conditions.

The data shows that the average investor does not stay invested long enough to reap the market’s rewards for more disciplined investors. The data also shows that investors often make the wrong decision when they react.

But here is the only question that matters in the active/passive debate:

“What’s more important – matching an index during a bull cycle, or protecting capital during a bear cycle?”

You can’t have both.

If you benchmark an index during the bull cycle, you will lose equally during the bear cycle. However, while an active manager focusing on “risk” may underperform during a bull market, preserving capital during a bear cycle will salvage your investment goals.

Investing is not a competition, and as history shows, treating it as such has horrid consequences. So, do yourself a favor and forget what the benchmark index does from one day to the next. Instead, match your portfolio to your personal goals, objectives, and time frames.

In the long run, you may not beat the index, but you are likely to achieve your personal investment goals, which is why you invested in the first place.