The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) of the Chinese Communist Party announced on Sunday that 405,000 officials at all levels were punished during the first nine months of 2023.

Of those targeted, 34 were “senior officials at provincial or ministerial levels,” according to the state-run Global Times.

As Chinese state media publications are prone to do when touting the achievements of Communist Party agencies, the Global Times rattled off some huge numbers for the latest purge of allegedly corrupt officials:

China dealt with more than 36,000 corruption-related cases impacting the public interest in the first half of 2023, with more than 52,000 individuals receiving criticism, education, assistance or punishment, China’s highest supervisory and anti-corruption authority announced.

From January to September 2023, discipline inspection and supervision authorities across the country received 2.617 million reports, of which 819,000 were tip-offs or accusations.

Of the 470,000 filed, 133,534 officials at all levels were involved.

CCDI said it received over 20,000 “tip-offs” this year. Authorities processed 12,000 bribery cases and a vast herd of Communist officials were marched into “education and rectification” programs.

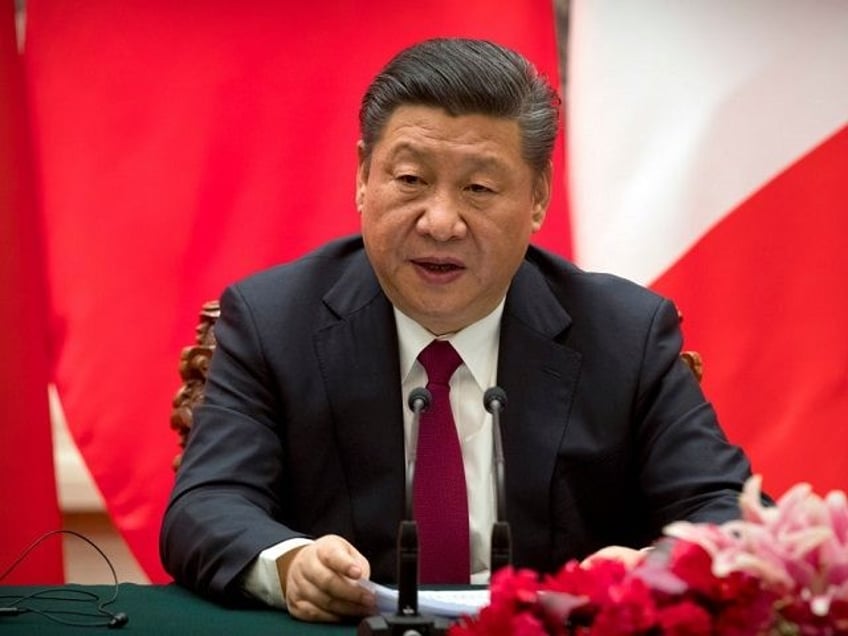

These are huge numbers, given that dictator Xi Jinping has supposedly been fighting an all-out war against corruption ever since he took power in 2013. A remarkable 3.7 million Communist Party members were punished by anti-graft agencies over the ensuing decade, comprising almost one percent of the total Chinese Communist Party leadership. Xi is constantly praised for battling corruption, but never criticized for government figures that would suggest it gets worse with every passing year.

The UK Guardian noted in April that much of Xi’s “anti-corruption” crusade is really just an ongoing effort to consolidate power by purging the Chinese Communist Party of dissidents and rivals. The result has been a climate of “intense scrutiny,” as Johns Hopkins University professor Yuen Yuen Ang put it.

“The campaign extends beyond fighting graft and into enforcing ideological conformity with the party line,” Ang said.

The Guardian observed that Xi’s rolling anti-corruption purge is “popular with the Chinese public,” which has noticed that achieving high public office is a sure-fire path to immense riches under their socialist system. Crushing and humiliating a few of the most ostentatiously wealthy officials seems to soothe public anger. According to one study, 91 percent of the officials convicted of corruption under Xi were among the richest one percent of the Chinese elite.

Another reason for all those corruption prosecutions is that Chinese business tycoons tend to become closely linked with politicians who enable their success, so when the businessman fall out of favor with Xi’s inner circle, their political patrons suddenly find themselves under investigation.

These politicized prosecutors tinted by Xi’s “personal mistrust of financiers,” and his antipathy for tycoons he feels have become less loyal to his authoritarian government because they have so much close contact with foreigners.

Xi’s purges are not always staid affairs in which the targets shuffle off to rectification centers in a flurry of paperwork. Some very high-ranking Chinese officials have vanished or died under murky circumstances over the past few months, including Foreign Minister Qin Gang, who vanished suddenly and was incommunicado for months before regime insiders began leaking stories in September that he was sacked over an extramarital affair with a mistress in the United States; Defense Minister Li Shangfu, who vanished for over two months before he was publicly fired for unclear reasons last week; and Xi’s formal rival Li Keqiang, who became his second-in-command until March, and died suddenly last Friday.

The elderly Li’s death from a heart attack at 68 did not seem inherently suspicious at first, but the Xi regime has labored to make it look suspicious. Regime censors are deleting social media posts hailing Li as a “reformer” and ordering students not to make public expressions of grief for the former premier’s death. Some Chinese social media users view the regime as panicking after Li’s death, and they feel it is not implausible to suggest Xi had Li killed to prevent the public from embracing Li as a less authoritarian alternative to the current dictator.