Marine creatures use light for various purposes, such as startling predators, luring prey and finding mates

Thirty-four sea turtles return to the ocean in Georgia after rehabilitating for months

A few dozen sea turtles were released back into the ocean after going through rehabilitation programs over the last few months. The turtles were taken to Jekyll Island in Georgia for the big moment.

- A recent study suggests that deep-sea corals from 540 million years ago might have been the first animals to glow.

- Marine creatures use light for various purposes, such as startling predators, luring prey and finding mates.

- Soft coral species in the deep sea exhibit bioluminescence, which researchers studied using remote-controlled underwater rovers.

Many animals can glow in the dark. Fireflies famously blink on summer evenings. But most animals that light up are found in the depths of the ocean.

In a new study, scientists report that deep-sea corals that lived 540 million years ago may have been the first animals to glow, far earlier than previously thought.

"Light signaling is one of the earliest forms of communication that we know of — it’s very important in deep waters," said Andrea Quattrini, a co-author of the study published Tuesday in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

INCREDIBLE BIOLUMINESCENT WAVES CREATE STUNNING SCENES ON CALIFORNIA BEACHES

Today, marine creatures that glimmer include some fish, squid, octopuses, jellyfish, even sharks — all the result of chemical reactions.

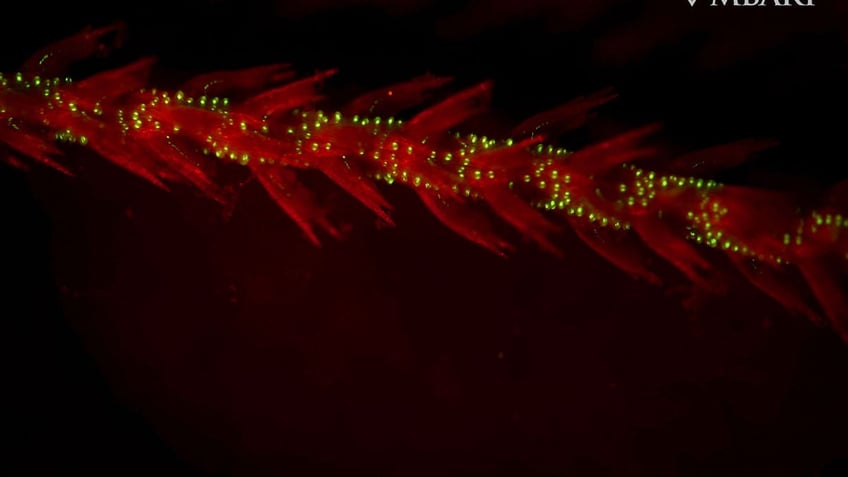

This image provided by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in April 2024 shows bioluminescence in the sea whip coral Funiculina sp. observed under red light in a laboratory. A new study suggests that the first animal that glowed in the dark was a coral that lived deep in the ocean about half a billion years ago. (Manabu Bessho-Uehara/MBARI via AP)

Some use light to startle predators, "like a burglar alarm," and others use it to lure prey, as anglerfish do, said Quattrini, who is curator of corals at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Still other animals use light as a beacon to find mates.

Many deep-sea soft coral species light up briefly when bumped — or when stroked with a paintbrush. That’s what scientists used, attached to a remote-controlled underwater rover, to identify and study luminous species, said Steven Haddock, a study co-author and marine biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

GLOWING, BRIGHT BLUE PHENOMENON OFF AUSTRALIA'S COAST SEEN IN STUNNING IMAGES

Soft coral may look like waving reeds, skeleton fingers or stalks of bamboo — and glow pink, orange, white, blue and purple under the researchers' spotlight, he said.

"For some species, the whole body glows — for others, only parts of their branches will glow," said Danielle DeLeo, a study co-author and evolutionary marine biologist at the Smithsonian.

For corals, scientists aren't sure if this luminous reaction is meant to attract or repel other organisms, or perhaps both. But its frequency suggests that it serves a crucial function in many coral species, she said.

But how long have some coral species had the ability to glow?

To answer this question, the researchers used genetic data from 185 species of luminous coral to construct a detailed evolutionary tree. They found that the common ancestor of all soft corals today lived 540 million years ago and very likely could glow — or bioluminescence.

That date is around 270 million years before the previously earliest known example: a glowing prehistoric shrimp. It also places the origin of light production to around the time of the Cambrian explosion, when life on Earth evolved and diversified rapidly — giving rise to many major animal groups that exist today.

"If an animal had a novel trait that made it really special and helped it survive, its descendants were more likely to endure and pass it down," said Stuart Sandin, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who was not involved in the study.