Last autumn, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi gave a speech in the New Administrative Capital in Cairo, the $300bn project that will ultimately define his presidency.

He said hunger was a small price to pay for progress: "If progress, prosperity and development come at the price of hunger and deprivation, Egyptians, do not shy away from progress! Don’t dare say: ‘It is better to eat.'" This horrifying vision of hunger and deprivation is what awaits millions of Egyptians in the coming years.

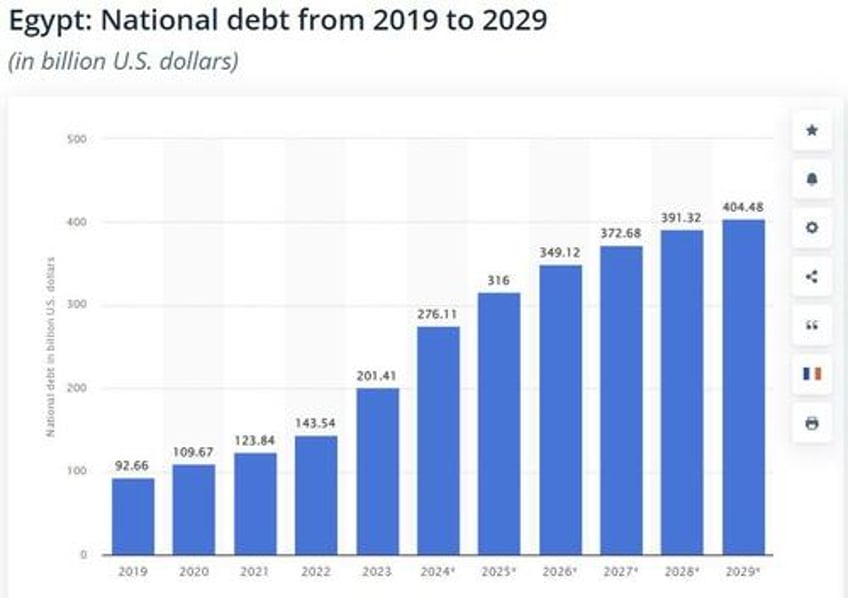

A decade after ascending to the presidency, Sisi has pushed the economy to the brink of collapse. The symptoms are everywhere. A severe debt crisis is strangling the state budget, the economy is heavily militarized, billions have been invested in white elephants with dubious economic benefits, and the crown jewels of the Egyptian public sector are up for sale to meet mounting debt obligations.

This all stems from the military’s desire to consolidate power and wealth in its own hands at any cost. This will have dire consequences that will be felt for generations - and recovery will take a mammoth effort.

Millions more people have been pushed into poverty in recent years, a trend that is expected to continue for the foreseeable future. In 2022, the poverty rate reached 33 percent, up from 26 percent in 2012/13, as the regime continues its policy of shifting the costs of the debt crisis onto the poor and middle classes.

The most obvious manifestation of this is the regime’s austerity measures - most crucially, the 300 percent increase in the price of subsided bread, the staple food for the most vulnerable people, which was announced in May.

Transferring wealth

This comes on the heels of price hikes for basic commodities, announced by the government in January. These measures are part of a comprehensive policy designed to transfer wealth from the poor and middle classes to the regime elites and their creditors.

The logic is simple: increased spending on mega-projects, financed by high-interest debt, has allowed the military to rapidly expand its economic footprint, while the repayment of debt is financed through the appropriation of public resources, which is in turn financed by a regressive taxation system.

This creates a diabolical cycle of structural poverty that is very difficult to escape. A cursory look at the current budget highlights this trend, with the main source of tax revenue deriving from a regressive consumption tax, yielding 828 billion Egyptian pounds ($17bn); in second position comes the tax collected from corporate profits, standing at a mere 239 billion pounds ($5bn). It is worth noting that 62 percent of budgetary expenditures will be consumed by debt obligations.

The increase in poverty will be accompanied by another structural transformation, namely the increased peripheralization of the Egyptian economy, which will become even more vulnerable to external shocks and to the goodwill of the regime’s allies.

The figures from the past decade are a testament to this. Despite a spending spree that has consumed hundreds of billions of dollars, the competitiveness of the Egyptian economy has not improved, nor has its industrial base. The contribution of the industrial sector to the GDP fell from around 40 percent in 2013 to 33 percent in 2022, a dramatic drop.

In terms of export performance, Egypt’s current account balance remains firmly in negative territory, deteriorating from minus two percent in 2013, to an expected minus six percent in 2024, based on data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This negative trend is expected to continue until at least 2029, based on the IMF’s available forecast.

Financing gap

This means that in the medium term, pressure will continue on the country’s foreign reserves, which in turn will apply pressure on the deteriorating value of the pound. The situation is compounded by the debt crisis, which is consuming much of the state budget, making public investments to increase economic competitiveness very unlikely.

Indeed, the debt burden is so large that even after receiving more than $50bn in recent loans and investment, the financing gap is still estimated to stand at $28.5bn. This means that in the foreseeable future, the Egyptian economy will require continued external support, in the form of loans and investments, in order to maintain a semblance of stability.

You will find more infographics at Statista

The most notable example is the $35bn investment by the UAE, announced in February, which was critical for avoiding a possible default or debt restructuring - that is, assuming the regime will be able to rein in public spending and put the brakes on its cronyism. Unfortunately, there are signs that this is not the case.

In May, the Egyptian army’s Engineering Authority announced its intention to continue with the third phase of the South Valley development project, which aims to reclaim around 40,000 to 60,000 acres by 2025. It is worth noting that in spite of several large reclamation projects of this kind, the contribution of agriculture to the country’s GDP dropped from around 11.3 percent in 2013 to 11 percent in 2022.

Thus, in all likelihood, the Egyptian economy’s dependence on external capital flows is set to deepen, leaving it susceptible to external shocks, the fickleness of regional politics, and the whims of international financial markets.

Grave consequences

The increased influence of Gulf capital in the Egyptian economy comes with grave economic consequences. Last September, an Emirati firm acquired a 30 percent stake in the government-owned Eastern Company, which controls 70 percent of the country’s tobacco market. The deal was valued $625m. The UAE has also financed the sale of a number of historic hotels for $800m.

This trend will only deepen the structural dependence of the Egyptian economy by depriving the government of important sources of pubic revenue, further straining public finances. This will continue to erode living standards, weaken the pound and send inflation soaring, while also strengthening the political alliance between the regime and its Gulf backers, creating further obstacles for the prospects of democratisation or improvements to workers’ rights.

The future of the Egyptian economy seems grim. Even if the prospect of debt default has subsided for now, the consequences of a decade of foolish economic policy have not.

The ongoing process of peripheralization will enrich a number of local elites, who will align themselves with these new realities. This is not limited to military elites, who will continue to benefit from the inflow of loans and capital, but it will also include civilian elites - the most notable example being Hisham Talaat Moustafa, an Egyptian real-estate tycoon and convicted murderer with close connections to the UAE. A partner in the historic hotels deals, his company’s profits reportedly jumped in the first quarter of 2024 by 220 percent.

Egypt is now undergoing a mass structural transformation, with millions of people plunged into poverty and wealth accumulating in the hands of a few, namely the military elites and their cronies. This transformation will have long-term consequences that are extremely difficult to predict. What is clear, however, is that the economic damage done by the regime goes beyond the debt crisis - and it will take years to reverse.