When Ellis, a 14-year-old from Texas, woke up one October morning with several missed calls and texts, they were all about the same thing: nude images of her circulating on social media.

That she had not actually taken the pictures didn’t make a difference, as artificial intelligence makes so-called “deepfakes” more and more realistic.

The images of Ellis and a friend, also a victim, were lifted from Instagram, their faces then placed on naked bodies of other people. Other students — all girls — were also targeted, with the composite photos shared with other classmates on Snapchat.

“It looked real, like the bodies looked like real bodies,” she told AFP. “And I remember being really, really scared… I’ve never done anything of that sort.”

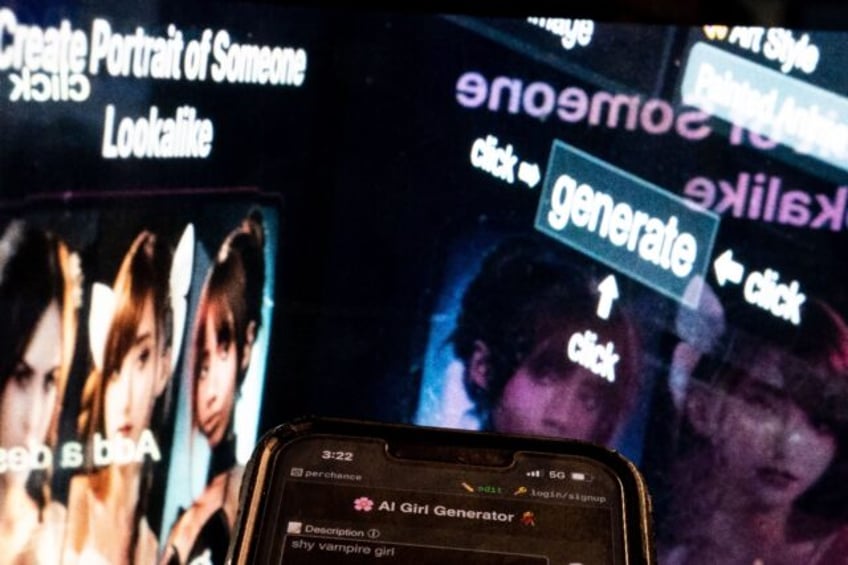

As AI has boomed, so has deepfake pornography, with hyperrealistic images and videos created with minimal effort and money — leading to scandals and harassment at multiple high schools in the United States as administrators struggle to respond amid a lack of federal legislation banning the practice.

“The girls just cried, and cried forever. They were very ashamed,” said Anna Berry McAdams, Ellis’ mother, who was shocked at how realistic the images looked. “They didn’t want to go to school.”

‘A smartphone and a few dollars’

Though it’s hard to quantify how widespread deepfakes are becoming, Ellis’ school outside of Dallas isn’t alone.

At the end of the month, another fake nudes scandal erupted at a high school in the northeastern state of New Jersey.

“It will happen more and more often,” said Dorota Mani, the mother of one of the victims there, also 14.

She added that there is no way to know if pornographic deepfakes might be floating around on the internet without one’s knowledge, and that investigations often only arise when victims speak out.

“So many victims don’t even know there are pictures, and they will not be able to protect themselves — because they don’t know from what.”

At the same time, experts say, the law has been slow to catch up with technology, even as cruder versions of fake pornography, often focused on celebrities, have existed for years.

Now, though, anyone who has posted something as innocent as a LinkedIn headshot can be a victim.

“Anybody who was working in this space knew, or should have known, that it was going to be used in this way,” Hany Farid, a professor of computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, told AFP.

Last month, President Joe Biden signed an executive order on AI, calling on the government to create guardrails “against producing child sexual abuse material and against producing non-consensual intimate imagery of real individuals.”

And if it has proved difficult in many cases to track down the individual creators of certain images, that shouldn’t stop the AI companies behind them or social media platforms where the photos are shared from being held accountable, says Farid.

But no national legislation exists restricting deep fake porn, and only a handful of states have passed laws regulating it.

“Although your face has been superimposed on a body, the body is not really yours,” said Renee Cummings, an AI ethicist.

That can create a “contradiction in the law,” the University of Virginia professor told AFP, since it can be argued that existing laws prohibiting distributing sexual photos of someone without their consent don’t apply to deepfakes.

And while “anyone with a smartphone and a few dollars” can make the images, using widely available software, many of the victims — who are primarily young women and girls — “are afraid to go public.”

Deepfake porn “can destroy someone’s life,” said Cummings, citing victims who have suffered anxiety, depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Fake photos, real trauma

In Texas, Ellis was interviewed by the police and school officials. But the education and judicial systems appear to be caught flat-footed.

“It just crushes me that we don’t have things in place to say, ‘Yes, that is child porn,'” said Berry McAdams, her mother.

The classmate behind Ellis’ photos was temporarily suspended, but Ellis — who previously described herself as social and outgoing — remains “constantly filled with anxiety,” and has asked to transfer schools.

“I don’t know how many people could have saved the photos and sent them along. I don’t know how many photos he made,” she says.

“So many people could have gotten them.”

Her mother, meanwhile, worries about if — or, given the longevity of the internet, when — the photos might resurface.

“This could affect them for the rest of their lives,” she says.