Many amateur French sports clubs are struggling to cope with a wave of enquiries and a boom in wannabee players sparked by the Paris Olympics.

“We’re a bit overwhelmed,” Catherine Groc, president of a fencing club in the trendy Marais district of the French capital, told AFP. “It’s been 10 days now that I’ve been turning people away.”

She says around 50 people came to try out the sport during two separate beginners’ sessions organised this month, meaning she expects to end up with around 30 percent more duellists compared with last year.

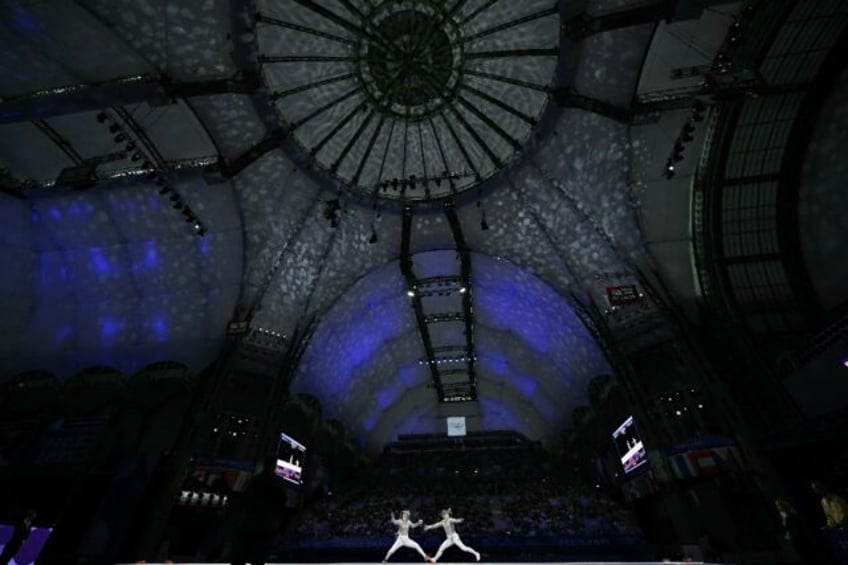

Fencing was given top billing on French TV during the July 26-August 11 Paris Games, with the home nation continuing its medal-winning tradition in the spectacular 19th-century Grand Palais which hosted the competition.

“After each Olympics there’s an effect, but this time the Games were in Paris, of course, but I think above all there is the Grand Palais effect,” Groc continued. “It was an absolutely incredible place, extraordinary.”

Other sports too have seen an influx of people eager to explore a new discipline or resume playing after years of inactivity — sometimes with disappointing results.

Swimming clubs have registered around 10,000 new members, while table tennis clubs are expecting around 20 percent more players.

The head of the French handball federation, Philippe Bana, told reporters last week that there was a “tidal wave” of new inscriptions in his sport, with demand up 18 percent this year compared to last.

“But indoor sports are near saturation point with their facilities,” he explained, saying that around 100,000 people would be turned down by handball clubs alone.

“The Olympics Games should be a springboard, not a closed door,” Bana said.

– ‘Mass of young people’ –

Each modern Olympics has ambitions of using the competition to generate interest in grassroots sport and physical activity, which produces a range of health benefits.

The French government and Paris 2024 organisers were no different in promising to leave a legacy that would help tackle the problem of people spending too much time on screens and doing too little exercise.

Among French children aged 11-17, three out of four do not meet recommended levels of physical activity, according to data from the National Observatory of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour (ONAPS), while obesity is also on the rise.

The country as a whole is classed 119 out of 146 countries when ranked by the amount of physical activity done by its adolescents, according to figures from the World Health Organisation.

For those in the sports world, having to turn away prospective players is frustrating — and runs counter to stated public health objectives and the goals of the Games.

“We haven’t got the means to welcome the mass of young people who are coming forward, and we’re talking about a mass,” Yves Bouget, head of the French national volleyball league, told AFP last week.

“That’s the real problem at the moment: facilities are full for handball, basketball, volleyball and badminton which use the same ones.”

The Paris 2024 budget saw most spending focused on renovating existing sports facilities in the Paris region or building temporary infrastructure such as the stadium inside the Grand Palais which was used for fencing and taekwondo.

Bouget called for a “Marshall Plan” of infrastructure-building to help increase capacity.

But with France’s new right-wing government under immense financial pressure, investment in sports is widely expected to be cut in the next budget later this year.

Capacity

Pierre Rondeau, a sports expert at the Jean-Jaures Foundation think-tank in Paris, said that academic research indicated that demand for organised sport typically increased by 15-25 percent after an Olympic Games in the host country.

“That’s in the short term, and you need to make a distinction between the short term and long-term,” he told AFP.

Some post-Olympics sports enthusiasts quickly lose their motivation, meaning clubs need to be careful about investing in new equipment.

But Rondeau stressed that the availibility of infrastructure was crucial, as well as qualified coaches.

“If everyone suddenly wants to go swimming or do judo and you don’t have pools or a dojo near you, then you’re going to have difficulty,” he said.

He cites the example of the landmark 2019 FIFA women’s football World Cup across nine cities in France as a cautionary tale.

“There was a surge in interest afterwards among women to play football, but it didn’t translate into an increase because there wasn’t enough capacity to absorb the increase in demand.” he said.