Gerald Levin, who led Time Warner Media into a disastrous $182 billion merger with the internet provider America Online, has died at the age of 84

Gerald Levin, the former Time Warner CEO who engineered a disastrous mega-merger, is dead at 84By DAVID HAMILTONAP Business ReporterThe Associated PressSAN FRANCISO

SAN FRANCISO (AP) — Gerald Levin, who led Time Warner Media into a disastrous $182 billion merger with the internet provider America Online, died Wednesday at the age of 84, according to media reports.

Levin had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, although his cause of death was not immediately reported. The former executive’s grandchild, Jake Maia Arlow, confirmed his passing to the New York Times and the Washington Post, but did not reply to a request for confirmation from The Associated Press.

Levin joined Time in the early 1970s as the company was just starting to shift its focus from print magazines to cable television. A lawyer-turned-idealist who had spent a few years working for an international development company in Colombia and Tehran, Levin found himself captivated by the transformative potential of business, particularly that of cable television, according to “Fools Rush In,” a 2004 book by journalist Nina Munk.

Levin once even drew an equivalence between his newfound passion and his former development work, according to the book, saying “there’s very little difference between water, electricity and television.” That perspective led him in 1972 to a position as vice president of programming at Time’s fledgling cable network, Home Box Office, later to be known simply as HBO.

Within two years, Levin, then HBO president, managed to convince Time brass to invest the then-immense sum of $7.5 million to distribute HBO’s signal via satellite, negating the need for even more expensive investments in laying cable or building microwave networks across the U.S. In September 1975 that link went live, making it possible for the company to broadcast the highly anticipated boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier — known as “the Thrilla in Manila” — live to HBO subscribers.

Within the company, Levin was soon known as “the resident genius,” according to Munk’s book. By 1980 he was running Time’s video group and biding his time. In 1987 he was chief negotiator for a massive merger between Time and the Hollywood studio Warner Bros., and not long after was the executive charged with warding off a hostile bid by another studio. He ultimately succeeded by arranging a $14.9 billion, all-cash purchase of Warner in 1990 that saddled the merged company with debt.

It took Levin another two years to claim the CEO title at Time Warner and another four years of warding off additional offers and managing internal squabbles to hit upon his next big idea. This was the so-called “information superhighway,” which Levin called the Full Service Network. It was an early conception of an always-on, interactive entertainment and communications network that the company promoted but never came close to actually building. Meanwhile, Time Warner shares languished.

Levin and his lieutenants had managed to completely overlook the internet, which eventually managed to bring full-scale interactivity to homes, businesses — and phones — around the world. That wasn’t obvious at first, of course. Only in mid-1997, when Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates invested $1 billion in the cable company Comcast to push forward its internet service plans, did investors start to grasp the value of cable networks as internet providers.

At about the same time that AOL, one of the early pioneers of online social services, was looking for a way to use its internet-inflated stock to acquire concrete assets. CEO Steve Case set his eyes on Time Warner, reckoning its tangible entertainment assets and cable network would do nicely. When he finally got Levin on the phone, Case not only suggested a merger, but told Levin that the Time Warner executive should be CEO of the combined company.

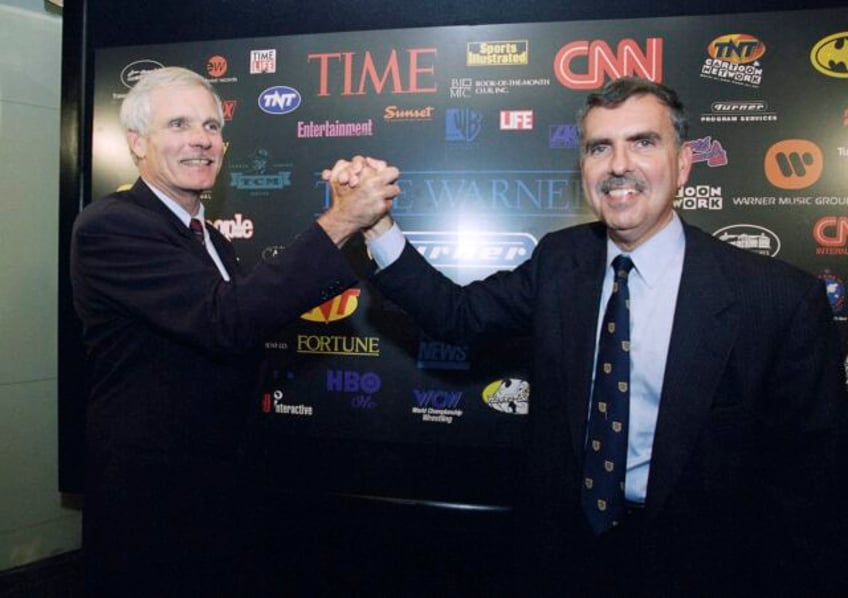

Levin wasn’t interested. On paper, AOL was worth roughly twice as much as Time Warner, but to Levin it seemed overvalued thanks to internet-related hysteria. But he agreed to meet Case for dinner, just to talk. The two hit it off, and that evening, Nov. 1, 1999, the men essentially agreed to a “merger of equals.”

The two sides wrangled over how much of the combined company they would each control, with AOL insisting on holding the majority thanks to a stock price that just kept rising. Finally, in the early hours of Jan. 7, 2000, Time Warner agreed to accept a 45-55 split, with AOL holding the larger share. Three days later, the Wall Street Journal broke news of the pending $182 billion deal, and the companies issued a formal announcement later that morning.

Striking that deal, hard-fought as it was, turned out to be the easy part. Even during the negotiations, Levin’s people found their AOL counterparts boorish and boisterous, while the AOLers thought Time Warner execs were plodding, stodgy and unable to fully comprehend the value of the internet. Those ill feelings didn’t subside over time, particularly once AOL shares plunged during the deflation of the dot-com bubble.

Levin hung on as long as he could, but hit a breaking point in the fall of 2001 when he began exploring an acquisition of AT&T’s cable system without consulting Case, who was furious when he learned about it. Shortly after Thanksgiving, Case gave Levin an ultimatum: Resign or be fired by the board. Levin, believing he was beaten, abruptly announced he would take early retirement the following May.

In 2002, the company posted a loss of $98.7 billion, a corporate record. Time Warner dropped “AOL” from its name in 2003, and in 2009 spun off AOL as a separate company, unwinding the merger to which Levin had devoted so much effort.