It was a little over a month ago when Goldman, wearing the bank's traditional "commodity supercycle" bull cloak, predicted that oil could hit $107 in 2024 as the oil market faced a 2 million barrel/day deficit in Q3 and Q4, a number which eventually would grow to 3mmb/d... and this was even before the break out of the Israel-Hamas war on Oct 7.

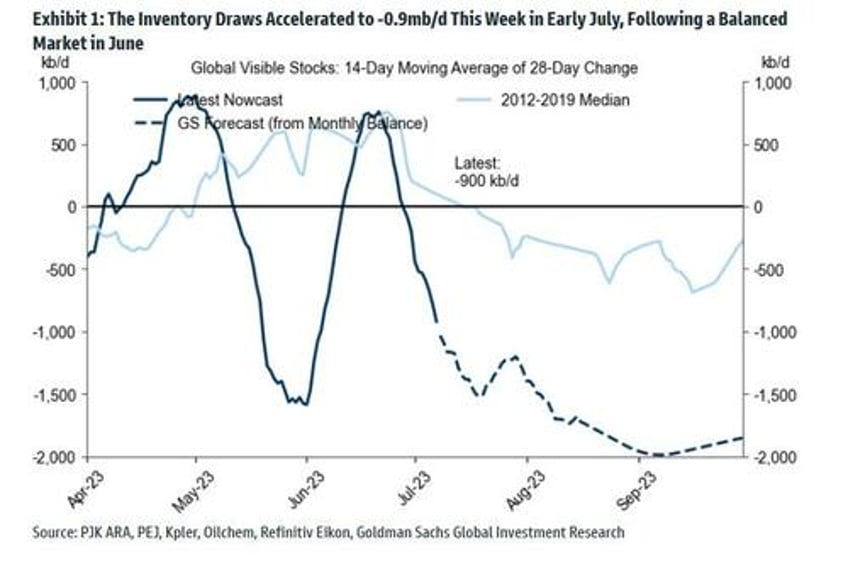

And yet, fast forwarding to today, and a mystery emerges: the deficit that Goldman and so many others predicted based on real-time supply/demand models is... nowhere to be found. And thus emerges a mystery that Goldman strategist Callum Bruce addresses today in the bank's latest oil-linked note (available to pro subs in the usual place), in which he reminds readers that before the conflict in the Middle East returned a geopolitical risk premium to the crude market, Brent prices had fallen more than $10/bbl from late September. Why? Well, in part at least because Goldman's high frequency global inventory tracker had "not shown the large inventory draws over the last five weeks that we and most forecasters had been expecting based on supply-demand balance estimates."

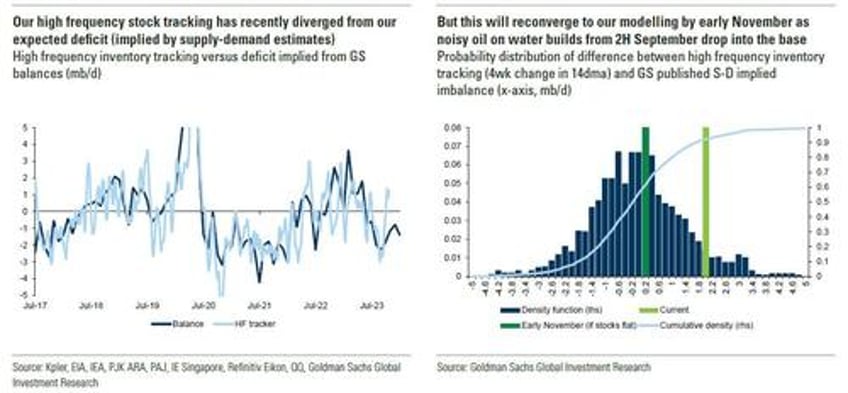

Specifically, as of 21 October, Goldman's high frequency tracking of oil on land and water via satellite data, vessel-tracking, and high frequency refined product stocks data showed a 0.8mb/d build over the last four weeks (on a 14dma basis), versus the bank's expected September/October imbalance of -1.8/-1.1mb/d, respectively.

This large divergence between the mostly consensus deficit and the bank's inventory tracker estimates of around -2mb/d is 1.7 standard deviations softer than normal, and sits in percentile 90 of the historical distribution.

What explains this divergence and is the underlying trend still an oil market deficit?

One possibility proposed by Bruce is that this divergence reflects that we are not observing significant refined product draws that will later appear in lagged monthly data (assuming the initial balances were correct) "because our ability to track inventories is better for crude oil than for refined products." However, in practice, the recent collapse in refinery margins and physical indicators for refined products suggests this is not the case. This is in line with Goldman's previous expectations that "super-normal profits" were likely to incentivize marginal refiners to increase utilization, sharply drawing down crude stocks, oversupplying refined product markets, and normalizing refining margins in the process. So if not for unobserved product draws, what explains the divergence then?

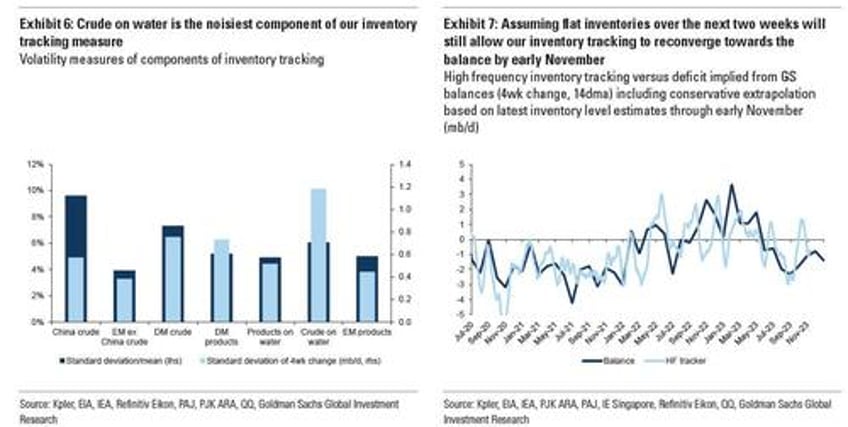

The next chart, (exhibit 4) shows that oil on water, both crude and products, more than fully explains the 40mm barrel rise in Goldman's high-frequency inventory tracker over the past 5 weeks, with large contributions of 30 and 20mb, respectively. Outside of these water-borne stocks, the bank's inventory tracker actually drew -10mb over the same period. The build in our tracker was also concentrated in 2H September, with overall inventories drawing slightly since then.

Having identified the source of the inventory build up, which we find somewhat perplexing since just a few days ago, Vortexa separately reported that the amount of crude oil held around the world in floating storage fell to 63.54m bbl as of Oct. 20, that's the lowest since March 2020, and down 11% from 71.31m bbl on Oct. 13, Goldman goes on to caution that its inventory tracker and the fact that the bank's latest nowcast of OECD commercial stocks is now 27mb higher than the end of October balance forecast of 2,777mb "point to the risk of a softer balance." Even so, the bank's commodity strategists continue to forecast deficits of 1.1mb/d in 2023Q4 and 0.8mb/d in 2024, and believe that the underlying trend remains an oil market deficit for two reasons.

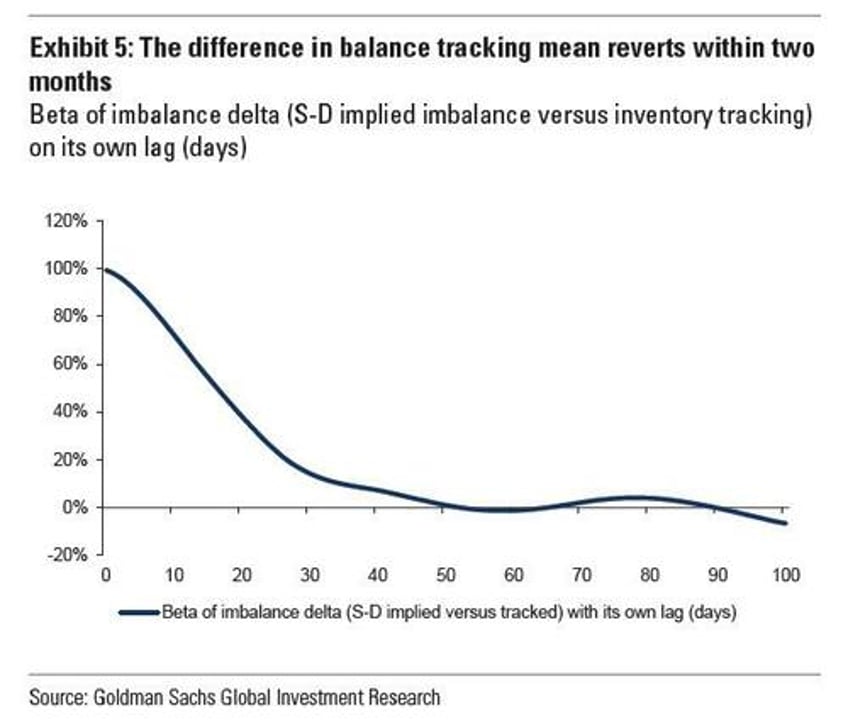

First, the high frequency inventory data are noisy and mean-reverting. The difference or ‘delta’ between the high frequency tracker and the deficit implied from monthly balances has a standard deviation of 1.2mb/d, with any divergence typically disappearing after 6 weeks.

Additionally, as noted above, "oil on water estimates" which drive the recent divergence, are particularly noisy and prone to revisions. In fact, the oil on water component of the inventory tracker is roughly twice as volatile as the other components (Exhibit 6). In fact, Goldman's high-frequency inventory estimate would essentially converge to the October deficit forecast of 1.1mb/d if one assumes inventory levels are flat for the next two weeks, when the jump in oil on water drops out of sample (here a quick footnote: as Bruce explains, "oil on water jumped in late September, followed by renewed draws in recent days. As such, given we use a 4wk difference in the 14dma, the high level from late September will soon roll into the base of our differenced measure. Just holding inventory levels flat at the latest reading will see this inventory measure deepen into a to -0.9 mb/d deficit by early November, just -0.2 mb/d softer than our September expectations of the October deficit.")

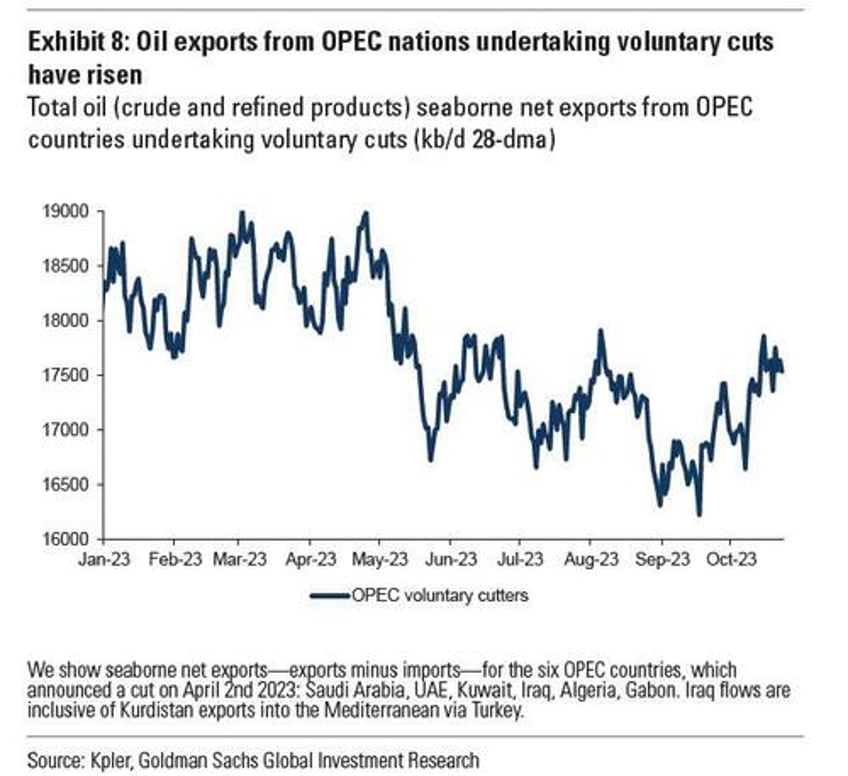

Second, the significant contribution to higher oil on water from rising exports by historically compliant OPEC members suggests that this softening is neither driven by a persistent drop in demand, nor by a persistent rise in non-OPEC supply, and is therefore likely temporary.

Specifically, oil exports from the OPEC countries that announced a voluntary production cut in April have increased by c.0.8 mb/d over the past month, and are c.1.2 mb/d higher than August levels, despite unchanged production quotas (Exhibit 8). This increase in exports alone explains more than half of the current c.2 mb/d difference between our inventory tracker and our deficit forecast. Oil in water has especially increased for Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iraq.

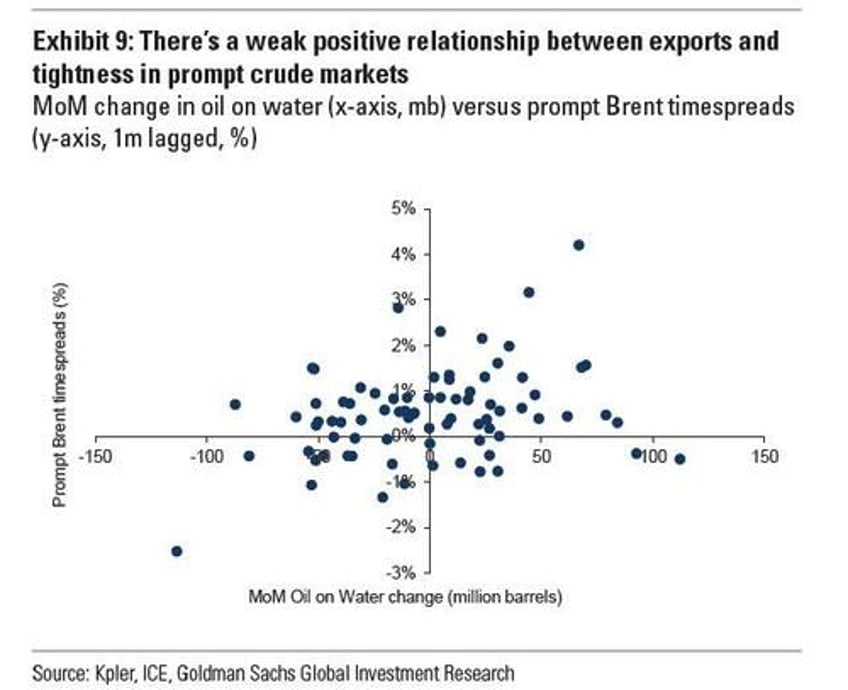

Now, because core OPEC countries have managed volumes with high compliance in recent years, Goldman expects their export flows to normalize. And while data limitations prevent the bank from ruling out an actual increase in recent production above production targets, one possibility is that some OPEC countries engaged in "domestic destocking" when prices overshot our inventory-based fair value in late September. Conversely, core OPEC export flows were quite low in August and in the first half of September when oil prices were lower, consistent with opportunistic restocking. More generally, the positive relationship between prompt crude spreads (1 month lagged) and the change in global oil on water suggests that export flows respond positively to price incentives.

To summarizes, Goldman resolves the riddle of the missing oil deficit by concluding that i) the volatility in high-frequency inventories data, ii) the composition of the recent builds, and iii) the bank's broader analysis of supply and demand fundamentals make it believe that the underlying oil market likely remains in deficit.

And while Goldman's commodities team says that it will continue to monitor high-frequency stocks and exports data very closely, it sticks to our "constructive" but range-bound view of the Brent forward curve, one which forecasts that "Brent rises to $100/bbl by next June, with oil prices likely to stay in an $80-105/bbl range."

More in the full Goldman report available to pro subs.