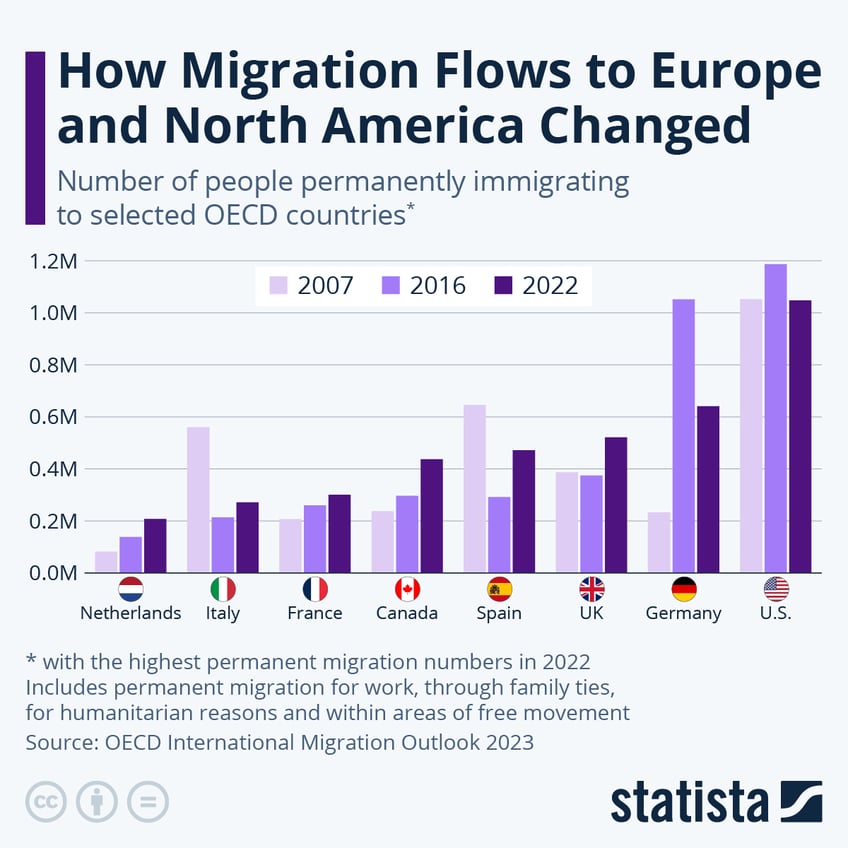

According to the newly released International Migration Outlook 2023, permanent migration to OECD countries reached a new high in 2022 at 6.1 million people.

Many developed countries that are part of the group accepted the highest numbers of permanent immigrants since their OECD records started around 15 to 25 years ago, among them Canada, France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

You will find more infographics at Statista

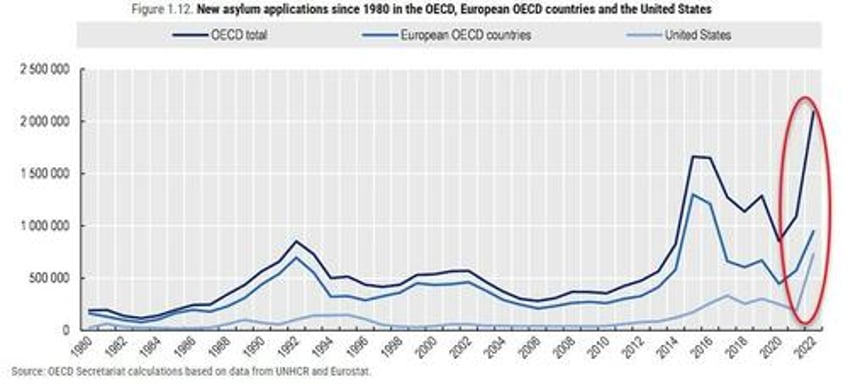

Additionally, as Statista's Katharina Buchholz reports, the number of international students and asylum seekers also reached a new high in 2022, the latter driven by a steep increase of application in the U.S.

The report concludes that the world is dealing with record high levels of displacement due to conflict, while many nations are simultaneously looking to fill labor shortages through skilled immigration.

Permanent immigration was dominated by those qualifying through family ties - an estimated 40 percent of all new immigrants across the OECD last year. In the U.S., this number was even higher at 69 percent in 2022, while in across the EU, 26.4 percent of new permanent migrants came through family ties, while 37.5 percent took advantage of the EU's area of free movement.

In some countries across North American and Europe, past years surpass 2022 in permanent migration numbers. For Germany, the year in question is 2016, when the country accepted more than 1 million new immigrants - around 40 percent for humanitarian reasons - as the Syrian civil war raged. The U.S. has seen more stable immigration figures since the OECD records started in 1996, with a high of 1.27 million reached in 2006. Spain and Italy saw their highest recorded permanent migration figures in 2007 after after an earlier peak of arrivals across the Mediterranean and the Atlantic in 2006 and a simultaneous easing of immigration law in Italy.

Among the countries which kept their permanent immigration far below pre-pandemic levels are Australia, the Czech Republic, Japan and South Korea - all countries whose governments have been critical of or at least very timid around migration. Permanent migration also remains slightly below 2019 levels in Norway and Sweden.