I’ve spent most of my 47-year career on the lookout for attractive investment opportunities in low-quality (“junk”) and distressed bonds. It’s what I did at Morgan Stanley… at Merrill Lynch... at BNP Paribas… and what I do now at Porter & Co.

One day in the 1990s, when I was the director of high-yield research at Merrill Lynch, I went to a roadshow presentation in New York by the CEO of a high-flying telecom company that was looking to sell $100-million-plus of bonds (by today’s standards that’s not a large issue – but adjusted for inflation, and in the context of the bigger issuance sizes of today, it wasn’t small at all). In that pre-Zoom era, the way companies usually marketed their issuances was through lunch presentations in major financial centers. The CEO and CFO would make their case to high-yield analysts from institutional money managers.

(I attended many roadshows. Attendees knew not to ask tough questions following the presentation. It was an implicit part of the arrangement. Probe too deeply… and you probably wouldn’t be invited next time around. There were consequences to the silence, though. A lack of genuine give-and-take meant that serious flaws in a company’s finances and business plans were not addressed… often leading to painful losses for bondholders.)

During a lunch I sat next to the CEO, who mentioned that he’d just been in Singapore. “Why?” I asked, as at the time it wasn’t a regular stop on the high-yield roadshow circuit. “I was looking to raise some equity over there,” he said. “But then I heard the window for issuing zero-coupon, high-yield bonds was open. So I cut short the stock sale and caught the first plane back to New York to take advantage of the opportunity.” (More on what zero-coupon bonds are below.)

Radically changing plans so abruptly, from selling shares to selling bonds – a decision that’s critical to a company’s balance sheet, financial trajectory, and long-term planning – isn’t the way big public companies normally operate. Low-rated companies’ operating earnings cover their interest costs by relatively thin margins – and backing away from a chance to raise equity in order to ease the debt burden isn’t ordinarily something to make a snap decision about.

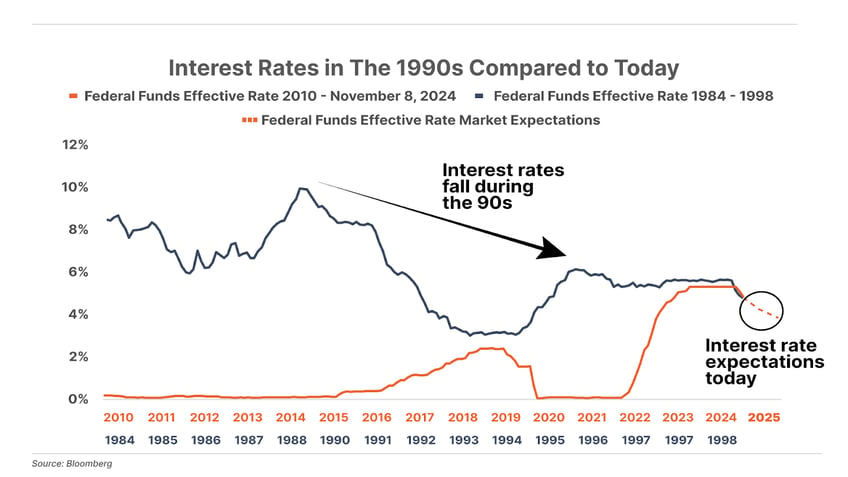

But this was no ordinary time. Much like in the current market, investor enthusiasm for high-yield bonds had been running super high. Then, like now, the Federal Reserve was injecting vast amounts of capital into the financial system by cutting short-term interest rates. When the Fed starts pumping up the money supply, that money eventually goes looking for somewhere to get invested. In such an environment, even companies that aren’t particularly creditworthy manage to raise capital in the new-issue high-yield market.

To cite a classic Wall Street phrase, there was too much money chasing too few deals – and the globe-trotting CEO wanted to take advantage of that dynamic. He wanted to sell bonds at a good price – rather than sell a part of the company via a share sale.

The “zeroes” the CEO was so eager to peddle are a form of financing that flourished when the bargaining power was skewed toward the issuing company and away from investors. These bonds are sold at a substantial discount to their $1,000 face value – and since they pay no interest, the only return comes from the appreciation from the discounted price to maturity. For the first several years, the company doesn’t have to shell out any cash for interest payments – hence the name “zero.” Only if the structure includes cash payments on the back end – the last few years before maturity – do bondholders receive any income.

And during the years when the company is not paying any interest, it receives tax deductions on imputed interest – interest the IRS acknowledges that you paid, even though you didn’t actually pay it. It’s done to be sure the bond holder pays tax for the entire duration of the bond, and not just on the back end – when interest is actually paid.

What a deal! A tax deduction on interest that the company doesn’t have to pay. No wonder that CEO had been so desperate to get back to New York before the window closed!

Since the 1990s, zero-coupon bonds have become a less-prominent feature of the high-yield market. But they’re a perfect example of an extreme imbalance of power between speculative-grade companies and bond buyers that still applies today.

Unless they’re in dire financing straits, companies usually have some flexibility about when they go to the market with a new issue. They have the luxury of being able to tap investors only when supply/demand conditions tilt the terms in their favor. That is to say, that’s when the balance of power for negotiating rates and terms puts investors at the maximum disadvantage.

Actually… there isn’t any negotiating to speak of. If orders for a new issue exceed the total amount being offered, the underwriters can simply dictate the price and provisions – take it or leave it, they say.

How to Take Advantage of This Power Imbalance

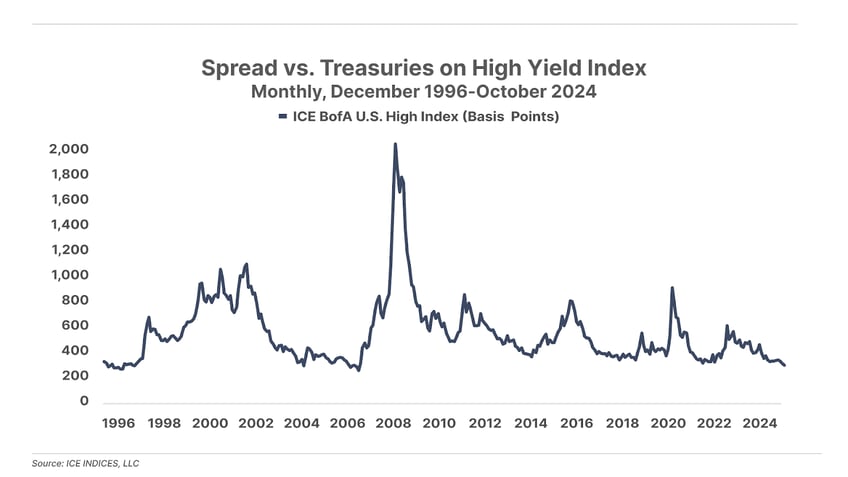

And in the current environment, with high-yield bond spreads at their tightest levels since 2007, the issuers have an unusually strong hand.

This raises a question: If new issues are offered to investors only when market conditions strongly disfavor them (that is, when they’re getting less return on their money), why do those big institutions purchase new issues? Can’t they find more attractive offerings in the secondary (resale) market when demand isn’t exceeding supply?

The practical impediment to that strategy is that the leading high-yield bond buyers, like BlackRock, Franklin Templeton, T. Rowe Price, and many other asset managers and major hedge funds, manage billions of dollars that need to be invested in the market. They don’t want to own a lot of different issues. It’s easier to keep track of fewer positions that are larger – rather than a lot of smaller positions.

As a result, the big players have little choice but to rely heavily on the new-issue market – because with these they can buy tens of millions of dollars’ worth of an issue in just one transaction. They’re buying bonds that have a less favorable risk-reward ratio than issues that are already in the market, because they have no choice – the liquidity of bonds in the secondary market is generally too low for them.

These dynamics, though, create a nice advantage for small investors. If, as a small investor, you’re looking to buy just a few thousand dollars’ or so worth of a high-yield bond issue, you can fill your needs in the secondary market. You’ll likely need patience until your order gets filled – but since you’re not looking to buy a large lot, you can find much better deals than new issues, where the bond issuer holds all the cards. (Finding these far more compelling bonds – which large investors mostly ignore because it’s not worth their while to buy small lot sizes – is what we do in Distressed Investor.)

Here’s some more good news: Distressed investors may not have to wait too long for market conditions to turn strongly in their favor. Shortly after high-yield spreads reached lows similar to today’s in 2007, the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 unfolded. Currently, only 4% of outstanding high-yield bonds are trading at distressed levels. In 2008 that ratio got as high as 84%.

We won’t necessarily see that level of distress, but things can change quickly. When the big institutions are once again choking on distressed debt, investors who have kept some cash ready for just those circumstances will have a huge profit opportunity. In 2009, the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Distressed Index as a whole delivered a 57.5% return, with many individual issues doing far better than the average.

Even in that kind of environment, you have to be choosy about which bonds you buy, but that’s when being in the driver’s seat feels really good.

Porter & Co.,

Stevenson, MD

Get The Daily Journal in your inbox… Every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, Porter Stansberry will deliver his Porter & Co. Daily Journal directly to your inbox. He puts his 25+ years of investment knowledge into a punchy, fresh, and insightful issue… that is free to get, no strings attached. Everything is uncensored, and nothing is off limits. To get the Daily Journal, free, click here.