U.S. President-elect Donald Trump has frequently lambasted other NATO countries for failing to fulfill their financial obligations toward the military alliance. But when he returns to the White House in January, he could find a lot less resistance.

European nations’ appetite for greater defense spending has been sharpened by the war in Ukraine and by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s continual saber-rattling.

EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said on Nov. 28 that the NATO bloc needs a “massive” defense spending boost—the latest of many European political heavyweights to do so.

But how much exactly has each county been they been contributing? How do the contributions compare historically? How much are members spending on the Ukraine war? And how much more might they be willing to spend?

What Are NATO’s Current Targets?

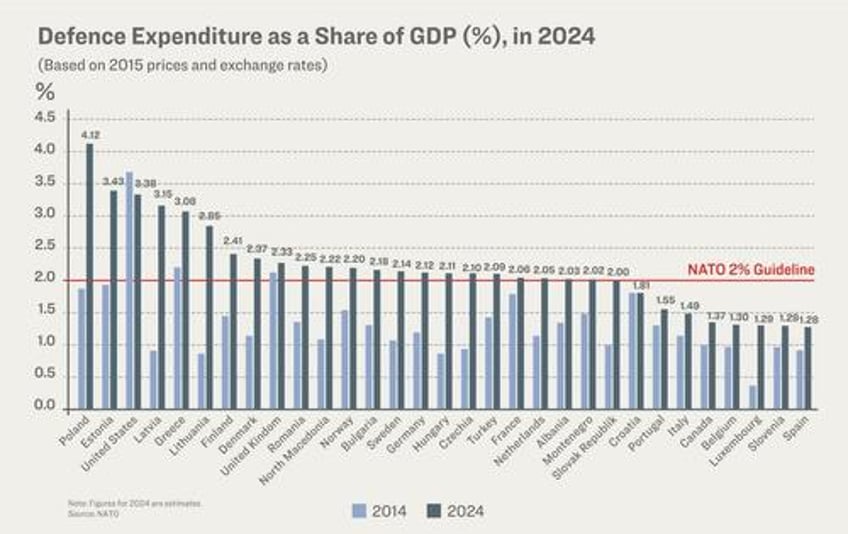

In 2014, NATO set a target that all members should be spending 2 percent of their GDP by 2024.

In July 2023, at a summit in the Lithuanian capital Vilnius, NATO members signed a communiqué which restated the 2 percent minimum, but added, “We commit to invest at least 20% of our defence budgets on major equipment, including related research and development.”

Official NATO figures for 2023, published in March this year showed only 10 of the United States’ 31 NATO allies had met the 2 percent GDP spending target. But in just one year, according to provisional NATO estimates for 2024, published in June, that number has now risen to 23 out of the 31.

So who is hitting the target and who are the laggards?

Poland—the NATO country closest to Ukraine—spent 4.1 percent of its GDP on defense (up from 1.8 percent in 2014).

That is more than the United States, which this year is spending an estimated 2.7 percent of its GDP on defense.

NATO says U.S. defense expenditure is approximately two-thirds of the alliance’s overall spending.

Greece—who has traditionally been a big spender because of the possibility of conflict with neighboring Turkey—is spending 3 percent of GDP, and the Baltic countries, for obvious reasons, forked out a similar amount.

Romania, which neighbors Ukraine, contributes 2.25 percent of its GDP, up from 1.6 percent in the space of only 12 months.

Last week, an independent candidate who has criticized NATO and the European Union, Calin Georgescu, won the first round of the Romanian presidential election.

Britain exceeds the 2 percent barrier but after becoming prime minister in July, Keir Starmer declined to say when his Labour government would hit its own target of 2.5 percent.

France came in just above the target, at 2.06 percent.

Germany, whose political and military muscle could be significant, has broken through the barrier this year and now spends 2.12 percent

Turkey, which is now on 2.09 percent, has also hit the target in the last 12 months.

The Turkish military not only garrisons the northern part of Cyprus, which it has occupied since 1974, but has also been involved in the Syria conflict, which is bubbling up again.

In recent days terrorist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham seized the city of Aleppo in northern Syria.

Among of the lowest spenders in NATO are the Canadians, who spend 1.37 percent.

On Nov. 25, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Canada was on a “clear path” to reaching the defense spending target of 2 percent of GDP by 2032, which is eight years beyond the target date set by NATO.

At the bottom of the list is Spain, which spends 1.28 percent of their GDP on defense.

Spain only joined NATO in 1982, and its defense spending was far higher before it joined, especially prior to the death of the dictator and former general, Francisco Franco, in 1975.

By comparison, Ukraine is currently spending 37 percent of its GDP on defense in 2024, while Israel will have spent far more than the 4.5 percent it reported in 2023.

How Has Spending Changed?

NATO was formed in 1948, three years after the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union defeated Nazi Germany and the empire of Japan.

The United States had initially stayed out of the Second World War—which was triggered by German expansionism and aggression—but was drawn in after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

The British Empire, which had just granted independence to India and Pakistan, was in a terrible state financially, as was France, while Germany was in ruins and still years away from the industrial miracle which would make it Europe’s richest nation.

In 1955 the Soviet Union created the Warsaw Pact—an alliance of communist countries in Eastern Europe—which was set up in response to the creation of NATO.

Defense spending stayed relatively high during the Cold War but, according to a table in an academic paper by Jarosław Wołkonowski, a Polish-Lithuanian historian, it fell gradually depending on individual countries’ commitments.

Canada—which was involved in the Korean War—spent 7.37 percent in 1953, but this fell to 2.15 in 1970.

France spent 5.89 percent in 1962—at the tail-end of the colonial war in Algeria—falling to 3.77 in 1980.

Britain spent 7.66 percent in 1956—the year of the Suez Crisis—and was still spending 4.46 percent in 1981, when it was involved in the conflict in Northern Ireland.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, global defense spending fell, reaching its nadir—$1,144 billion—in 1996, down by one-third from the $1,730 billion spent in 1988.

Germany was unified, and thousands of U.S. troops were withdrawn from Europe.

But in 2000, President Vladimir Putin came to power and Russia, boosted by exports of oil, gas and minerals, became an economic power again and increasingly sought to flex its political and military muscle.

Since then a graph in a NATO press release tells the story in stark detail.

Read the rest here...