Soweto’s Vilakazi Street is packed each day with tourists and hawkers outside the home of Nelson Mandela that has been meticulously kept even as the democracy pioneer’s legacy has become rundown in the decade since his death.

Ntsiki Madela, who lives nearby and sells jewellery and hats on a table near the matchbox house museum at number 8115, is among many South Africans who feel let down.

While thankful that Mandela’s 16-year presence in the township now draws tourists, the 47-year-old said: “I haven’t seen any change from Mandela’s democracy and I don’t even see the need to vote.”

With a legislative election due in months — the 30th anniversary of South Africa’s first democratic vote — authorities are struggling to get people like Madela to register.

Voter numbers have fallen with every election since the first in 1994. And the people who do vote are increasingly turning against Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) that has ruled since then.

Polls suggest the scandal-tainted ANC’s vote share could fall below 50 percent for the first time as Africa’s biggest economy slumbers and corruption taints its image.

Inequality rules

Unemployment is among the world’s highest at 32 percent of adults and wages for those in work are low.

Despite the end of apartheid, South Africa has the world’s lowest equality ranking, according to the World Bank.

The government and state firms are carrying more than $300 billion of debt and the figure worsens every day.

Street crime and murders have also grown over the past decade and some days Madela and her neighbours go without electricity for almost 12 hours a day.

“We only have enough income to feed our kids, there is constant load-shedding and the cost of living is unbearable,” said Madela, referring to the chronic power cuts.

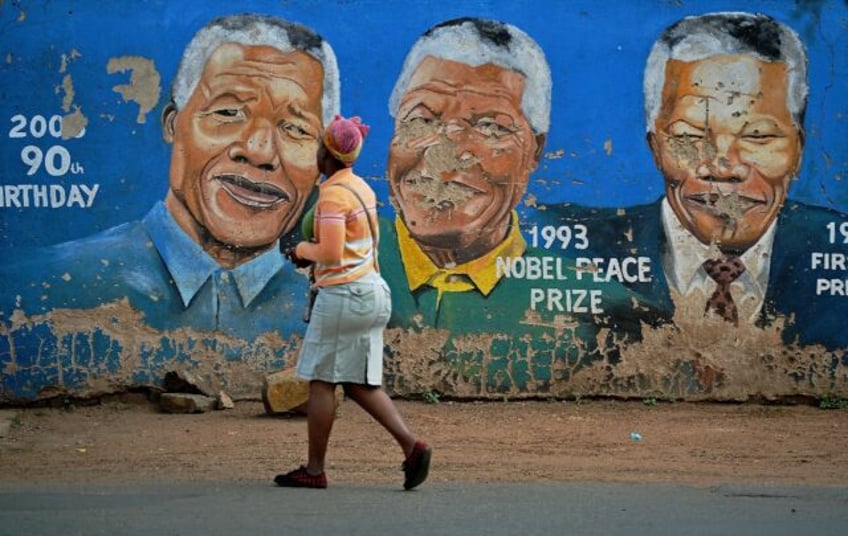

Mandela is seen around the world as a moral compass for the way he wore down white minority rule and his vision of a multi-racial South Africa.

Critics say the ANC leaders who took over quickly dropped Mandela’s torch.

Mandela’s legacy has been “undermined” by his own party officials who are “corrupt” and have “deviated” from his “moral consciousness”, independent political analyst Prince Mashele told AFP.

Nic Borain, a political analyst working in financial markets, said there was a “kind of mythology” around the Mandela years that meant anyone following would struggle.

Power crisis

The government and the ANC have as big a fight on their hands to tackle apathy as they do debt.

Former president Jacob Zuma, who was forced out of office over corruption allegations, only avoided prison because of his poor health and a remission approved this year by his successor, President Cyril Ramaphosa.

In June the graft watchdog cleared Ramaphosa of allegations that he breached ethics by not reporting the theft of more than $500,000 in cash hidden in a sofa at his farm.

Down the road from Mandela’s house, 27-year-old teacher Sive Jizana sat with friends at a popular pub. Mandela’s legacy was “dying”, she said.

She noted the lack of running water and proper roads outside main cities. “And now we don’t have electricity,” she said.

Zandile Cubeni, a 24-year-old unemployed sociology graduate, said she would not join the voters’ list.

“A lot of my peers are jobless, we aren’t getting any tangible benefits,” Cubeni said, adding that Mandela’s legacy “has been made out to seem like something without any flaws, that’s not true.”

Some say Mandela’s name was over-hyped.

“We don’t really see what Mandela and all the others did for us… we are still poor,” a 43-year-old cashier, Thobile Cele, told AFP.

“We simply don’t even have a democracy anymore as long as… ANC is in power,” said Leigh-Ann Mathys, a member of parliament for the leftist Economic Freedom Fighters party.

She said courts had been “captured” to operate in the ANC’s favour and there are doubts about institutions like the electoral commission during the 2024 vote.

Some Mandela loyalists are trying to make the public look beyond the apartheid battler’s name to map out a future direction. But Mandela’s family is publicly keeping the faith.

His grandson, Mandla Mandela, an ANC lawmaker, said the party had achieved many successes and some “spectacular failures” but overall South Africa’s democracy was still “healthy”.

“The key evil of colonialism was that it robbed our people of their land, and this remains the litmus test for how we measure transformation,” the 49-year-old said.